What is to be done about the Welsh literature GCSE poetry syllabus?

Sara Louise Wheeler

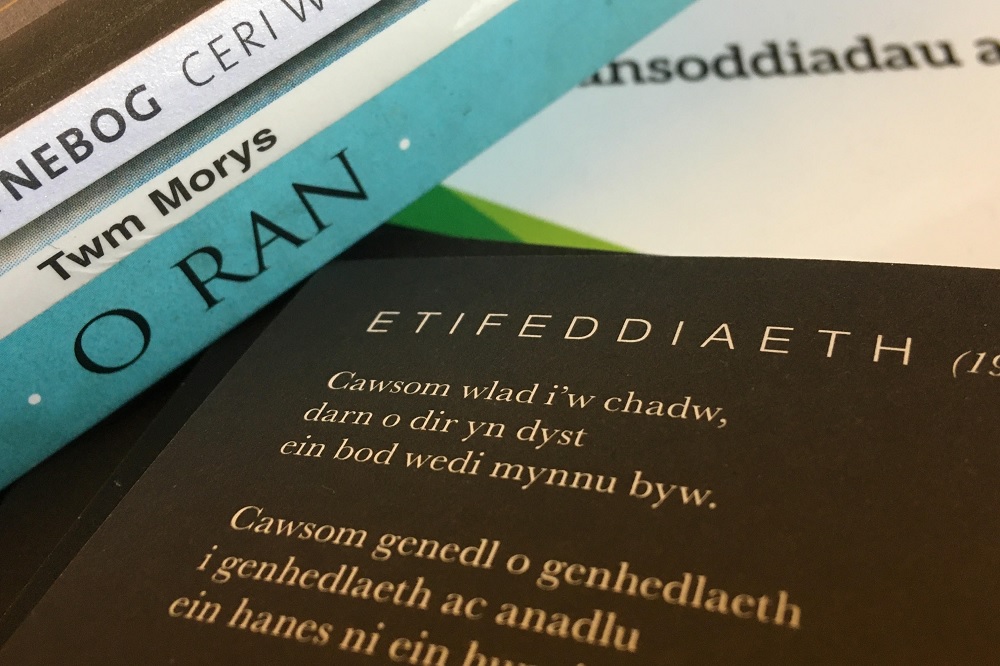

Last week, the spotlight fell on the ten poems Welsh literature GCSE students are currently required to study – or rather the poets who wrote them. In a Twitter thread, Welsh poet Iestyn Tyne drew attention to the fact that the demographic lacked diversity, particularly emphasising that only one out of the ten poets -Meredrid Hopwood – was female.

As a female poet myself, from a working-class background in the north-east of Wales, living with a plethora of health conditions and disabilities, I was intrigued. Having joined the discussion, I was invited, along with others, on to ‘Y Post Cyntaf’ BBC Radio Wales to discuss the matter further.

I decided to take a closer look at the ten poets and soon found that there was another problem which had not yet been mentioned – the north-east of Wales was notable by its absence; meanwhile, Gwynedd was overrepresented. Neither of these things surprised me, it is a common problem, but I felt it was important that this was not overlooked during the debate.

However, an unfortunate comment was made in return, to the effect that perhaps all the best Welsh poets were from ‘Y Fro Gymraeg’ – a label translating as ‘The Welsh Language Area’; unofficially, this is currently spread over the counties of Gwynedd, Carmarthenshire, Ceredigion, and Anglesey.

Nobody else appears to have found this comment problematic, and this cultural-geographic issue was not even mentioned in the subsequent article on the BBC website, and neither was disability.

Personally, however, I find the idea of the best poets emanating from one place to be rather dangerous rhetoric, as it would be in relation to any other characteristic, as it risks perpetuating the status quo, strengthening the ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’, underpinned by the idea of a ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ sort of poet.

‘The best poets’

The idea of ‘best poets’ needs unpacking. How do we evaluate the ‘best’ poets? Who’s in the pool of consideration? What, even, is a poem? And what are the criteria for putting them on the list? From here, we should consider what message the current composition conveys – as Llio Maddocks highlighted, all bar one on the list are white, straight men.

Obviously, we can all identify with poets on different grounds. Thinking back to my GCSEs, I don’t recall any female poets I studied, though I’m sure there were some. I identified best with I.D.Hooson, a white, male poet, from my father’s home village of Rhosllannerchugog. I liked the simplicity of his style and the familiar themes. All my early poetry was in this style of rhyming couplets.

However, the poet whose work has had the most lasting and dramatic impact on my poetry is Patience Agbabi, a poet born in London to Nigerian parents, who spent her teenage years in North Wales. In my twenties, I attended a course at Tŷ Newydd writing centre, where Welsh female poet Menna Elfyn gave us ‘The Wife of Bafa’ to read. It was completely different from anything I had ever read or written, but I loved it. This encounter had a dramatic impact on my writing. I bought her books, studied her poems, and switched to the ‘dramatic monologue’ style of poetry.

So, identification needn’t necessarily mean a matching identity – I though Agbabi’s gender was irrelevant. It was the vibrancy and power of her poetry and what she achieved through her literary devices that fascinated me. However, obvious gaps in the demographics of the poets on the core syllabus, with the overrepresentation of certain groups, is unhelpful.

The Welsh Government aim to increase the number of Welsh speakers in Wales by 2050 to 1 million. The north-east and the borderlands generally present a particular challenge in this regard, since transmission and practice occur predominantly through the education system, rather than social spaces.

It’s rather unfortunate, then, to be presenting children from the north-east with a syllabus they’re expected to study, but which does not represent their geographical community. However, this is also currently true for the syllabus, as far as I can tell, in terms of people of colour, LGBTQ, people with disabilities, and women.

I cannot be certain, however, since poet demographics are not shared, which seems to me to be a missed opportunity for engagement.

So what is to be done?

Whilst CBAC’s response was that these ten poems were the ‘set’ poems, and that teachers had the freedom to add a variety of poems to compare with them, it is still not acceptable for this core set to be so skewed and unrepresentative.

Obviously a fully representative, stratified sample would be almost impossible, and the principle of merit should be the main criteria. But improvements are certainly achievable.

In a previous role, I was involved in appointing to public bodies. The system we used involved having criteria which all candidates had to meet – but which did not inadvertently exclude anyone based on, for example, qualifications not required for the role.

We would then seek to appoint the best mix, in terms of representing a diversity of groups, through candidates’ active involvement as well as being from those groups. I would suggest that something similar might be helpful here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.