Ant Heald shares the story of Tania Szabó and her heroic mother Violette’s short but extraordinary life

Ant Heald

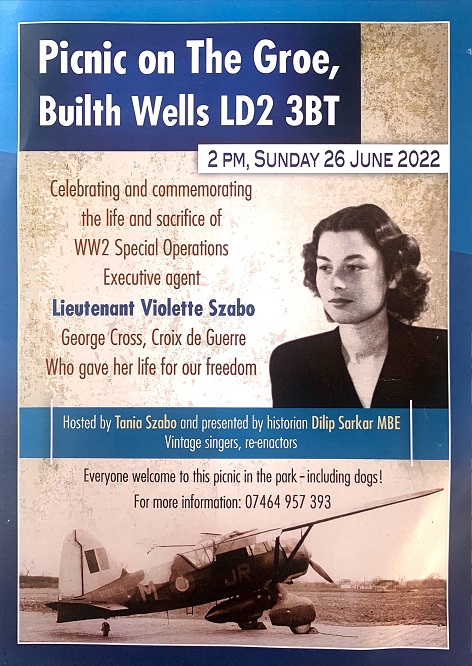

On the 26th June, a picnic will be held on The Groe in Builth Wells celebrating the 101st anniversary of the birth of Lt. Violette Szabó GC. Centenary celebrations took place last year, but were restricted by Covid regulations.

This year, it is hoped that the public celebration will be on a scale that Violette’s short but extraordinary life deserves.

Violette Szabó is one half of the most highly decorated married couple of World War II.

She met her husband, Etienne, a French-Hungarian Foreign Legion Officer, at a Bastille Day parade in London in 1940, marrying him after a whirlwind romance just two years before he was killed at El Alamein, without ever seeing their daughter, Tania.

Violette, a fluent French speaker, who was born in Paris to a French mother and English father before settling with them in London, was then recruited to the Special Operations Executive (SOE) to be parachuted behind enemy lines, gathering intelligence and supporting French resistance networks.

On her second mission in 1944, after a gunfight with German soldiers, she was captured, tortured, made to work in concentration camps, and eventually executed at Ravensbrück.

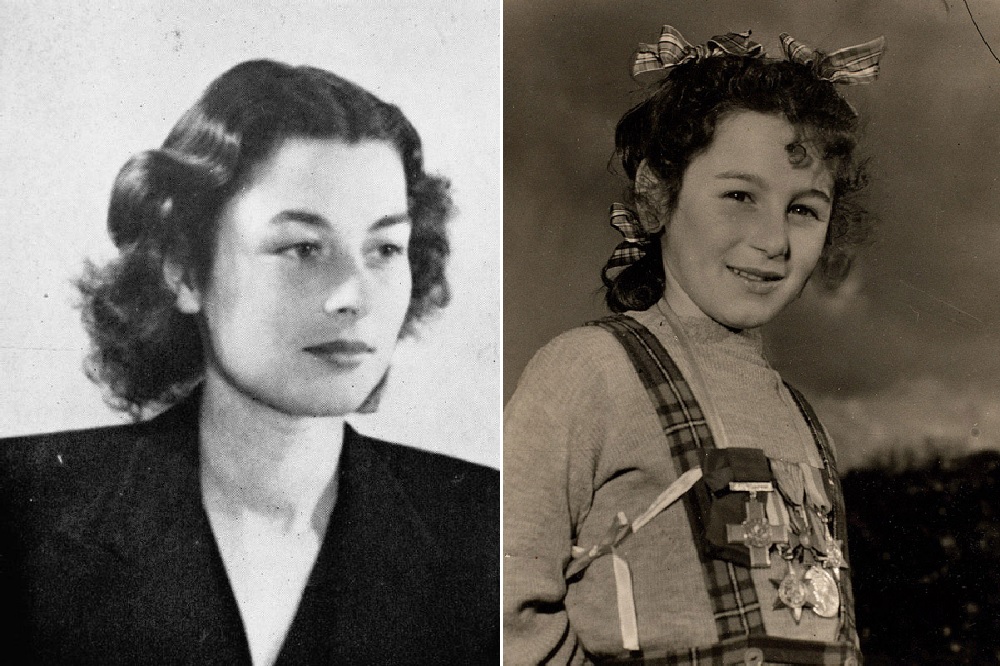

Two years later, in 1946, at the age of just four years old her daughter Tania received the George Cross on her behalf, the highest civilian award, from king George VI.

So how has Wales become the home of the forthcoming public celebration of the remarkable exploits of this brave young woman?

I visited Tania Szabó at her home in Cilmeri, just outside Builth Wells, to find out, and discovered a woman whose own story, if not as dramatic as that of her mother, is compelling in its own right.

Vivacity

On arrival, I am greeted by a lively collie, Mick, and an equally sprightly woman whose vivacity makes it difficult to believe when she tells me preparations are underway for her eightieth birthday, just a couple of weeks before the picnic for her mother’s 101st.

Tania ushers me through her modest house cluttered with books, into a surprisingly spacious back garden where she serves a delightful lunch as we chat.

Looking around, she says “I’ve never called a place ever — and I’m old now — I’ve never called a place home, never, but here. Except perhaps when I was a child.

“On my French side, my mother’s great grandmother came from Wales, right? It wasn’t really my choice, and wasn’t I lucky, because I don’t want to live anywhere else.

“It’s so beautiful, and gradually I began to make friends and so on. It’s a beautiful place. I’ve done the cities and big countries but, no, this is nice. And I don’t need a big place; just me, and that animal.”

She looks over at Mick gnawing a bone on the lawn.

Over the next couple of hours, given the places she has been and the life she has lived, I will find out not only how grateful Tania is to have found a home here, but how honoured Wales can be for her to call it home.

She points out her writing shed, and the insulated outhouse where the archives and almost a thousand books accumulated over many years of researching the story of Violette are temporarily housed until they can find a permanent home.

“I needed a pantechnicon,” she says, of the amount of material transported from her previous home in Jersey, first to a rented 17th century cottage near Builth, where a fire, discovered by Mick, fortunately spared both her and the precious archive, before she found her current home, which she says will be her last.

Retelling

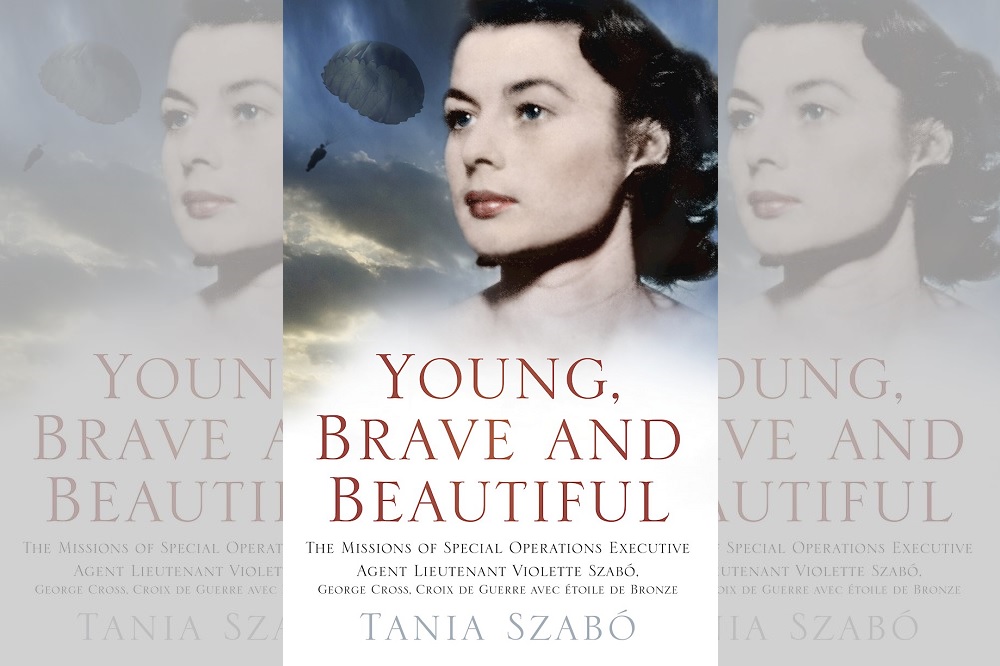

Tania’s book, Young Brave and Beautiful, the product of years of research and imagination, tells the remarkable story of the mother she can barely remember.

The book was first published in 2007 in Jersey, with a revised edition in England in 2015, the year that she also sold her mother’s George Cross, now displayed in the Imperial War Museum, to help secure the long term future of her Violette Szabó archive.

Tania’s book is not the only retelling of the story of Violette. In the 1950’s, R J Minney’s Carve Her Name With Pride led to a successful film starring Virginia McKenna OBE as Violette.

McKenna wrote a foreword to Tania’s book, and was also present at the opening of a small museum dedicated to Violette in the house in Wormelow, Herefordshire where Violette spent many childhood summers.

Known to her as ‘the old kennels’, the building is named ‘Cartref’, a Welsh connection that Tania only became aware of during her research.

When Tania mentions Minney’s book, she visibly flinches.

“It took me years to read it,” she says, “because I found it extraordinarily patronising. I would get so cross with him. Why is he writing like that? Where does he think he’s coming from? And so, as I wrote, all I wanted was to capture the essence of what Violette was. And of course, I grew up with the family telling me about her.”

Tania’s book has been well received by most readers, but there is a strand of criticism of her invented dialogue between Violette and other people that were obviously not recorded verbatim, if at all.

Tania describes how the Jersey book was originally much longer, with even more detail on the French Resistance than the considerable historical background it does contain.

She also tells me that she was encouraged to cut the many footnotes that substantiate and elaborate on the factual historical detail which she kept.

“So I agreed in the end to cut it down quite a lot for the English edition. I’m not a historian. I didn’t want to put myself out as a historian; I wanted to,” she pauses, takes a breath, then looks straight at me, “breathe life into her.”

She goes on to elaborate at length her method of working through all the documentary evidence of what happened, working out who must have known what, and when, and then inferring plausible scenarios of how that information might have been conveyed, and those plans made.

It is a method that arguably gives Tania more credibility for such an approach than a historian could have, as she spent time over the years in the places, and with the people still alive, that Violette had known.

Fictionalised conversation

She gives an example of a fictionalised conversation in the book between Violette and an SOE operative, Philippe Liewer, filling me in on details of a particular mission involving gathering of intelligence on the V-rockets being developed along the Seine.

“I felt, Violette has to know about that. So how is she going to know about it? I got Philippe Liewer’s personal file from the National Archives and there he’s described it all, and I thought ‘oh good, I can use that as conversation instead of boringly paraphrasing Philippe’s report’.

“Obviously it’s my imagination that’s created it, but the facts all come from this report, so Philippe must have one way or another given that information to Violette.

“And I know he had that little bedroom that was John’s in Burnley Road [Violette’s parents’ London home]. I know how small it was with the little bed and little chair and lamp, so I could see them sitting there talking about it in French. And with my grandmother running around doing this that and the other.

“It’s not just some made up story. It must have taken place somewhere, and that seemed an ideal place because he was staying there, and she would have spent time in there as they were planning for them to be off on her first mission. Does that make sense?”

I reflect that it makes a lot of sense, and that this immersion in historical fact as a means to bring historical figures to life in literary form has a strong and respectable pedigree. It is the approach taken by Hilary Mantel, for instance, when writing about Thomas Cromwell.

Tania does not lay claim to such literary ambition, any more than to being a professional historian, but what she uniquely brings to the telling of Violette’s story is a vivid personal connection to the people and events of Violette’s life.

But does this not, I wonder, risk the book being seen as a sort of hagiography? That she may have idealised her mother, or read her own character back into that of Violette?

She almost cuts me off, with a “No, no no,” and tells me about a warning given to her by Paul Holley, who had been an intelligence offer involved in Violette’s training, but later became Tania’s companion and mentor, helping to keep her language studio in Jersey operating while she worked on the book.

“He said to me, ‘Do not think you are her,’ and he made that very clear, and I understood precisely where he was coming from. We’ve got two different people here.

“And the other thing is I didn’t know Violette very well. I have three memories and that’s it. Violette for me was this young woman. You don’t have to be all emotional about it; I don’t get like that quite purposefully.

“You tread carefully in all of these matters. I was quite right in the way I wrote, and there’s nothing wrong with that approach, because it’s an honest approach. I wasn’t pretending to be something that I’m not.”

Echoes

During our conversation about the book, family details sometimes emerge that are not included within its pages.

She mentions the brief period of home-leave for her father, Étienne, before the mission at El Alamein where he was killed.

“One of those times,” she recalls, “they spent at the Adelphi hotel in Liverpool, which then was a very posh hotel, and very beautiful, because he liked nice things and wanted to do something beautiful for his beautiful wife. And that’s where I was conceived. Which is quite nice except – I’ve never been to the Adelphi. I want to go. One day maybe.”

The palpable sense of longing and regret swells as she goes on to elaborate the sense of Violette hearing about Étienne’s death, and grieving not only the loss of him, but of “the early flush of romance and love and the sexuality and lovemaking that goes with it. All of that is still so new. And it’s gone. And she’s lost him.”

She talks about how young Violette was, but that she’d also already had quite a bit of life experience.

“I mean 23 wasn’t as young then as it is now. She was 21 when she started training, and Violette had left school at 14 and then she ran away to France.”

Yes, we are of course dealing with two different Szabó’s here, but I can’t help but see echoes of her mother’s experience in Tania.

After emigrating with her grandparents to Australia on the ‘£10 transport’ programme, she too had an impetuous adolescence.

“When I started High School at 13 in Australia I was being a little bit naughty. My grandfather took me to the police station one day and got the policeman to give me a bit of a telling off which didn’t help very much. He told me I might end up at Reformatory which is Australian for borstal. I liked the idea of that.

“So my grandmother spoke to the headmaster of the primary school, and he turned out to be Catholic and thought it would be good idea if I went away to a Catholic college somewhere.”

Tania talks about the beautiful old building in Armidale, with its library and gardens.

“We had these Ursuline nuns, the equivalent of the Jesuits, and I thought I wanted to become one because we had a beautiful chapel where the nuns sang and it was just glorious. I loved it. I decided I was going to become a Catholic and learned everything I needed to learn.

“But, blind faith? I just couldn’t accept that. And mortal sin? I’m sure I committed one of those every day. Venial sins I might have done every hour! But I loved it there and received a top-class education.”

Courage

She developed an interest in psychology but decided against university.

“This was the 50s and the people who came out of university weren’t the kind of people I wanted to be, so I refused to go which upset everybody — but that wasn’t unusual — so I became a psychiatric nurse instead.”

Like Violette, she married young. They returned to England, but soon separated.

“I didn’t want children in a bad marriage. No pill then. It was a hard decision. I was castigated by everyone for walking out.”

The young Tania lived, for a time, a life that it is easy to imagine would also have suited the beautiful and vivacious Violette.

She found herself learning, and then teaching Spanish in Beverley Hills, dining and partying with the likes of Barbara Streisand (“She was kind of morose, sulky I think was the word, until she got interested and smiled, and then this beautiful person emerged”) and Herb Alpert and his wife (“They had a beautiful, beautiful dog, and a big place — big piece of land falling down to the ocean in Malibu, but a completely normal house, casual; I liked that place and I liked both of them.”

Like that Malibu garden, Tania’s life story tumbles casually as she takes me in a diverting series of anecdotes from Los Angeles to San Fernando Valley; delivering important papers for industrial deals; six months in Lanzarote, including cooking chicken in the heat of a volcano.

She spent some time back in London, with a visit to Wimbledon at the invitation of a famous Australian tennis player whose name she can’t quite remember.

“I’m sitting there watching the tennis when suddenly I had to write. I wrote this kind of poem about Lanzarote; it just fell out. And he came in after the match and said, ‘What did you think of that?’ And I had to tell him I’d missed it.”

There was one remarkable interlude that suggests that Tania’s character may to some degree have been shaped in Violette’s image when she suddenly says, “Oh, I’ll tell you something else which is quite funny, the Yom Kippur War. I decided — I’m not Jewish or anything — but I decided I would go over there and help. And my friends are saying ‘well what happens if you get hurt?’ – ah well, I won’t get hurt. I’m sure I can do some good.

“So I get my plane ticket from El Al, and it’s the first airline that did all the rigorous security, so eventually I got through and I got on the plane and it was wonderful. Here I am going off to war, with the admonitions of my friends ringing in my ear, ‘You bloody idiot!’ And all that kind of stuff.

“And suddenly half-way across the tannoy spoke, and it was a ceasefire. Too late! Too late! There I was in the middle of going to war, and they stopped it. It wasn’t fair!

“I spent two weeks in Israel. I’d been invited by two generals, because of Violette, and they decided to drive me up to the Golan Heights and I saw a blown-up tank, and another destroyed vehicle, and my voice started to rise because realised a bomb could be lobbed over.

“I had to keep pulling my voice down so as not to appear as scared as I was. I was scared. It was the funniest thing really. Where was my courage?”

A brief visit to a kibbutz followed, where “everybody is on an equal footing, and yet they keep changing who’s running things, and when they’re doing that part of it they’re quite bossy. Now I’m not good at that kind of thing.”

Diffident

So Tania became her own boss.

She tells me about her time as a beauty therapist in London, servicing wealthy clients, In 1976 she went to live in Jersey where she set up her language studio and taught a range of languages.

Although diffident about her abilities, claiming not be really fluent in any, she has taught or translated twenty-two different languages.

She talks about the wife of a Harry Patterson, who set up the Alexander technique, which Tania had been asked to do but declined, then casually remarks that Harry was “the writer, the Eagle Has Landed man, Jack Higgins” who provided another foreword for her book.

She was clearly happy on Jersey, running her language studio, learning so much and leaving a lasting impression on her students.

By coincidence, a couple of days after our interview I am talking to another writer about Tania when she stops short and says, “Tania Szabó? From Jersey? She taught me French!”

By now, lunch over, we have moved to the conservatory where Tania sits in front of a shelf with portraits of Violette and of Paul Holley next to her.

“Not long after I wrote the book, he died.”

She gestures at the picture of Paul.

“He was everything to me. And I had to make a decision. What do I do now? It was big decision, but it was the right decision.”

That decision was to move to Wales. Friends scoped out possible properties for her.

“So I came to Wales, and we drove up through mountains and it was so beautiful. I just loved it. And every time I go away and come back it’s like — it’s the land that’s grabbed me.”

Wisdom and fun

And it’s on this land next weekend, on the green sward of The Groe in Builth, between the Gorsedd stones and the meandering River Wye, that Violette Szabo’s remarkable life will be commemorated and celebrated with a picnic, with displays about Violette’s life and the work of the SOE, with a presentation from historian Dr Wyn Thomas.

A ceremony around the Cenotaph will commemorate not only Violette but all those fallen from the Gulf Wars, the Falklands and other conflicts including the Ukraine There will be vintage singers, and period re-enactors.

And there will be Tania.

In the epilogue of Young, Brave and Beautiful, Tania wrote of Violette: “What a great old lady she would have made, what a contribution she would have given and what wisdom and fun she would have passed our way.”

We can regret that life was cut so short and be thankful for the sacrifice she made.

But we can also be grateful that in giving birth to Tania Szabó, Violette did make a great old lady, in whose company I was gifted an afternoon of wisdom and fun.

If you can get to Builth Wells next weekend, take the chance to experience a little of that fun and wisdom for yourself as you celebrate the 101st birthday of Violette Szabó GC, that young brave and beautiful young woman ‘who gave her life for our freedom’.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Incredible story, and to think there was a Welsh connection. I recall reading Carve her name with Pride, in form 3 English , it was a terrific and horrific read . What courage these young people had. I urge you to read the book.