Best of 2021: Review of The Welsh Language in Cardiff – A History of Survival

This week Nation.Cymru are counting out the year by revisiting our literature highlights of 2021. This piece was initially published in January 2021 and was the most popular review of the year.

Jon Gower

In his introduction to this myth-debunking book BBC Wales’ Welsh Affairs Editor Vaughan Roderick suggests that it might perhaps be better to substitute the word ‘revival’ for ‘survival’ in its sub-title. It’s certainly the case that the fortunes of the language in the town and then city have waxed and waned over the centuries.

Yet the incremental growth of Welsh language schools during the past seventy years offers plentiful evidence of the language consolidating. Since the opening of Ysgol Gymraeg Caerdydd at Ninian Park Primary School in 1949 – when there were just 19 pupils in attendance – provision has grown to almost 8,500 attendees in 2018/2019, spread across 18 primary schools and 3 secondary schools. The general downward trend in language use in the census figures between 1891 and 1971 has also been reversed, with some 15% of the city’s inhabitants now able to speak the language.

The book is based on the author’s lifelong, extensive research, which included an MA on the history of the Welsh language in Cardiff. He draws on a commendably wide range of sources such as personal names, field names, diaries, legal documents and court records. The last of these turns up some colourful nuggets of information, not least when people were taken to court for slander, often because of things said by people in their cups, or at least in public houses. In 1735 the wife of the innkeeper of the Five Bells on Broad Street slandered a woman called Ann Watkin, describing her among other things as ‘y butain gomin losgedig oedd yn rhedeg ar gefnau’r gwŷr a gweision yn y Casbach,’ (the common burnt prostitute who ran on the backs of men and servants in Castleton.’)

Stronghold

The Welsh Language in Cardiff details many linguistic shifts and movements, starting with the Anglo-Norman era when there were only nine Welsh names listed among its inhabitants. Street names were in English throughout the centuries, even in places where Welsh was spoken freely, but the Welsh themselves did some re-baptising, so that the site of the current civic centre was known as Cae’r Fidfoel, the field of the bare hedge and City Road was Cae Pwdwr, the defiled field.

Pub names were usually English but these, too were called by other names, so that the King’s Head in Canton was known as Y Brenin and the Red House dubbed Y Tŷ Coch, while the landlord of the Red Cow in Womanby Street was known as Dic y Fuwch. A pub on Queen Street, the Glove and Shears went a little further by hanging a sign outside declaring ‘Cymry a Chymraeg tu fewn,’ (Welsh people and Welsh within).

Some of the local strongholds of the language mentioned in the volume are strikingly interesting such as Pentyrch, where, in 1861, 95% of the population were Welsh. The area was home to many miners as well as coal trimmers who worked in the docks and had no fewer than five Welsh-language chapels as well as a bilingual Church.

At the same time migration into the town itself was changing the linguistic picture, so that the American consul in Cardiff, the journalist Wirt Sikes suggested that “for the common uses of life the English language is as much the language of Cardiff as it is of New York” although he also noted packed congregations in the dozen Welsh language chapels of a Sunday.

However Welsh names were disappearing, with a well in Radyr called Pistyll Golau becoming Pitcher Cooler and the Lleucu becoming Roath brook, although the original Welsh name has now been resurrected. The late 19th century saw a clutch of chapels switch language, at a time when migration from the West Country, Ireland and Scotland rather than from rural Wales as had been the case in preceding decades, social changes begetting linguistic ones.

Characters

Tithe maps and estate maps were, of course, a rich source of information, with almost 90% of field names being Welsh, showing strong evidence of the language between 1700 and 1845. And job adverts could be telling, such as that for a clerk to the Cardiff markets in 1838, which insisted that any applicant had to be bilingual. Indeed, from 1758 onwards the Welsh weighing measures such as llestraid, pedoran and pedwran were compulsory in the market.

Welsh was also seen as beneficial in the retail industry and in 1891 two thirds of the staff at the David Morgan department store were Welsh speakers, as were half of those at nearby James Howells. In matters of faith, too the Welsh language had a prominent place. Out of the 18 places of worship established in the area between 1800 and 1840 all except two were Welsh in language.

The book also marshalls an interesting array of historical characters. One of these was Sir William Herbert, made First Baron of Cardiff in 1551 whose first language was Welsh. During the time of the Herbert family, the number of Welsh people living in the town swelled and Welsh bards such as Lewys Dwnn praised this family who lived in the castle, singing ‘Y Gaer fawr a gara fi… lle iachus dyn, lloches deg’. (The large fort that I love… A healthy place for man, a fair haven.’).

The second, third and fourth marquesses of Bute were also supporters of the Welsh language. On stage at the Cardiff National Eisteddfod of 1834 the second Marquess of Bute, who had been its biggest financial supporter, described Welsh as a ‘great storehouse of the people’s long-treasured recollections and the distinctive barrier of their nationality.’

Another colourful character was Cochfarf, a teetotal carpenter who ran a small chain of coffee houses in the town, became mayor of Cardiff and was one of those who built bridges between the Irish and Welsh communities.

In The Welsh Language in Cardiff Owen John Thomas has given us a very readable and detailed account of a language’s tides and ebbs. As both a politician and language activist he has himself played a busy role in promoting Welsh in recent years, not least by helping create Clwb Ifor Bach as an entertainment venue.

This fascinating book is another sterling contribution to the language’s longevity, as it charts the way social trends and movements affect a city which now, fittingly, has a Welsh language motto, ‘Y Ddraig Goch Ddyry Gychwyn’ (The Red Dragon Inspires Action.)

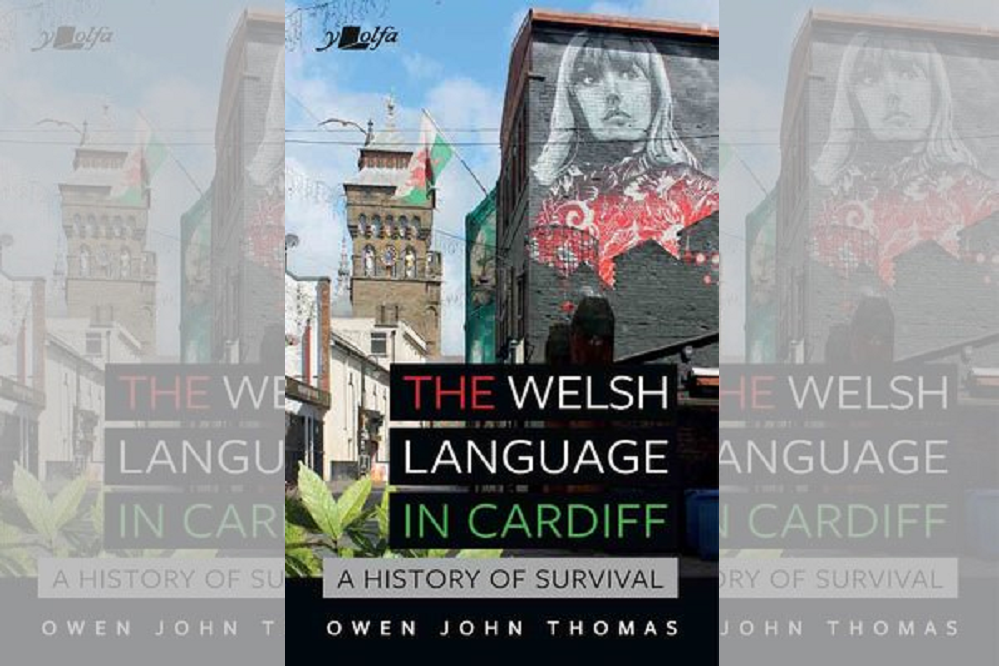

The Welsh Language in Cardiff is published by Y Lolfa or at your local bookshop

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.