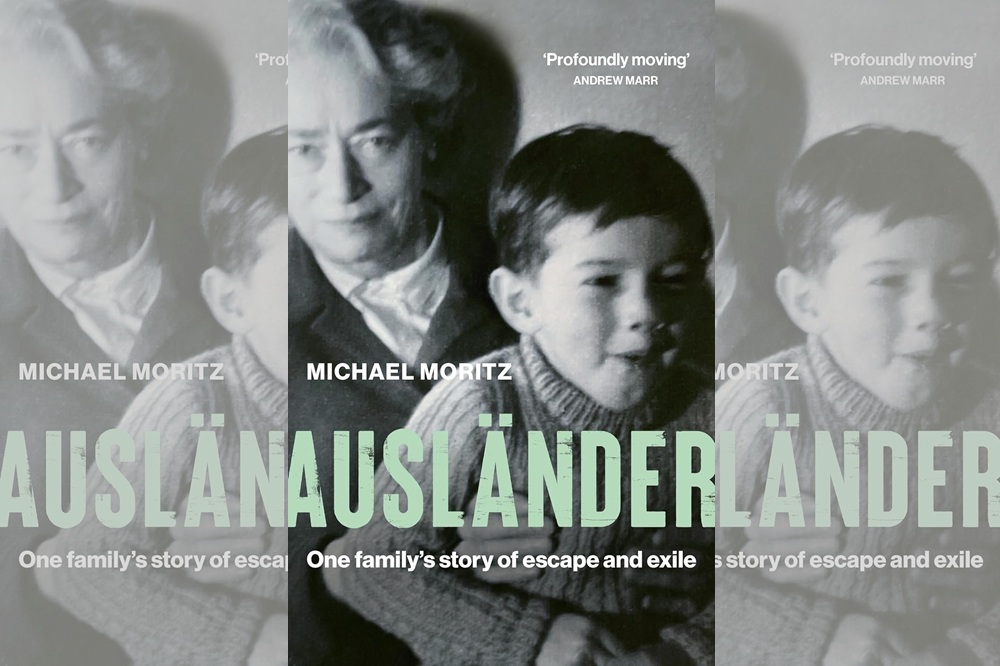

Book review: Ausländer: One family’s story of escape and exile by Michael Moritz

Desmond Clifford

Michael Moritz, originally from Cardiff but long-time resident in America, awoke to his Jewish identity in a serious way through illness.

He was diagnosed with a form of blood cancer rare among the general population but prevalent among Ashkenazi Jews originating from central and eastern Europe.

He re-evaluated his life and set about filling gaps in his family’s history left untold or under-examined by his parents. This book is the result.

The title, “Ausländer”, is German for “foreigner”. This appellation applies to his parents’ experience in Germany, their homeland, and, later, in different forms, in England and Wales, their subsequent homes.

Moritz himself, born and bred in Cardiff, feels an intergenerational version of this apartness among his schoolmates named Gareth, Rhys and Dewi.

Years ago, I took a train from Munich into Austria. I was a little bleary, perhaps a stein too many the night before, and dozed off. After a few minutes the train jolted as we arrived at our first stop: Dachau. I sat up, awake suddenly.

Dachau. I had no idea. I assumed all the Nazi camps were buried in the countryside, if not in Poland, away from prying eyes. So far as I could see, Dachau was a respectable looking dormitory town for Munich – but honestly, who could bear to live there now? (I returned some years later to seek out the camp, a predictably grim experience).

Michael Moritz’s great uncle, Oskar, spent two years in Dachau. Michael’s grandfather, Max, read the runes and sent his two sons to school in England.

As a result, the sons lived while Max and Oskar, trapped in Germany and relying on iron crosses, law and state institutions to save them, were killed in the Holocaust.

Michael’s mother, Doris, arrived at Liverpool St Station on the Kindertransport from Cologne, a station I’ve visited without a care in the world many times.

Doris’s parents escaped to England on virtually the last day in 1939 before the war made travel impossible.

Although schooled in England, followed by Oxford University, Moritz’s father, Alfred, having escaped Nazi Germany, was interned as an enemy alien on the Isle of Man once war began.

His brother was sent to a prison camp in Canada.

After the war, Moritz’s father, seemingly a gentle, deferential character, became professor of classics at Cardiff University, a post he found with some difficulty. Professor Moritz published little but devoted his energy to university administration and, after retirement, to his synagogue. He lived until 2003.

Moritiz’s mother displayed little joy or affection, unsurprisingly perhaps in view of her family’s history. She was prone to “great verbal violence” – especially to people closest to her – and was quick “with censorious verdicts”.

Even after 50 years in Cardiff she felt she was treated like a foreigner. Moritz cites a letter she wrote to the Sunday Times, in 2003, at the time of the Millennium Centre opening.

Moritz records that Bryn Terfel had expressed doubt whether Michael Howard, then Conservative leader and the son of Jewish immigrant parents in Llanelli, “was actually Welsh”.

In her letter, which wasn’t published, Moritz’s mother wrote: “My children were born in Wales, and I consider them Welsh, and so do officials when they realise that my son has done well in the USA. No doubt the same goes for Michael Howard.”

Moritz’s mother died just before the COVID outbreak, about which he is rueful because she would have regarded the pandemic as a vindication for her catastrophising worldview.

Claustrophobia

At her funeral in Cardiff, Moritz felt claustrophobia among the crowd: “I kept looking for the exit, and then I realised the source of my anxiety: I was packed into a small chamber with a couple of hundred Jews, all of whom were being funnelled towards a corridor leading to a crematorium.”

In a spare, almost austere, book, this sentiment stabs like a knife.

Michael Moritz was born in Cardiff and lived there till he was nineteen before Oxford, then America, beckoned.

He experienced anti-Semitism at school. Cardiff is possibly no worse than anywhere else for discrimination – the sadness is, that’s it’s no better either.

Moritz’s parents lived quietly, proudly Jewish, but trying to be as British or Welsh as the next person.

Moritz notes that, as he ages, “I have become increasingly conscious of the debilitating effects of the past on my behaviour.”

We might all feel some of that, but most of us don’t feel the Holocaust sitting on our shoulder.

A family tree illustrates precisely who among Moritz’s family perished. A photograph, reproduced in the book, of his great-uncle, Oskar Moritz, standing by the bus that transported him to death, was entered into evidence at the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961. The banality of evil, indeed.

Compelling

I am intrigued, but unsurprised, that Moritz is fascinated by “Austerlitz”, the strange, compelling German novel by W.G. Sebald.

It is the story of a man who passed his childhood in Bala with adopted parents, and his spent his adulthood trying to piece together his identity through memory, research and narrative.

The act of describing his life to his friend – the anonymous narrator in the novel – is what gives his life shape and meaning.

This is essentially what Moritz does with his family.

The resonance is clear: his mother arrived on the Kindertransport into Liverpool St Station in the same way as Austerlitz.

“Austerlitz” is the character’s real name but is better known as the name of a place, much like “Moritz”. With some alterations, “Austerlitz” might stand as a narration of Moritz’s family, a clear example of the trite observation, but not false on that account, that a novel sometimes captures truths more precisely than a history or memoir.

Identity

Moritz is pre-occupied with identity: “…during a lunch in San Jose, California, in 2001, the First Minister of Wales asked, “What’s a nice Jewish boy like you doing in Silicon Valley?”

The First Minister in 2001 was Rhodri Morgan. Moritz goes on, “my skin shrivelled and all my feelings about being Jewish and different from others in Wales in the 1960s came flooding back.”

Moritz attributes no malice to the First Minister but describes how “every slight”, every drawing attention to difference, connects back to the schoolteacher who thought it funny to have him read the part of Shylock from Shakespeare.

Moritz felt foreign, and was made to feel foreign, growing up in 1960s Cardiff.

The most terrifying part of the book is the rise of anti-Semitism in 1930s Germany.

Germany was developed and “civilised”, a land of law and institutions, a world of cocktail parties and classical concerts, an advanced and scientific society.

How did it become so quickly and so thoroughly a land of pogroms and state-thuggery? How did it so cheaply abandon humanity? How did Herr and Frau Ordinary, normally so decent, go along with it all?

In a book of tragic passages this, perhaps, is the saddest sentence of all: “The Moritz brothers – my father and uncle – found that they were also no longer welcome in the homes of friends from the previous summers.”

I was pleased to note that Moritz enjoyed a literary friendship with Jan Morris based on shared interest in Wales, Oxford and literature.

What Moritz doesn’t mention is that they were brought into contact by a small but civilised act of generosity from Moritz for a Welsh literary charity, recorded by Jan Morris in her penultimate book “Thinking Again” (2020).

Business investor

If you have previously heard of Michael Moritz, it’s likely because of his great success as a business investor.

He is often cited as Wales’s richest person but has maintained a relatively low profile. Having lived in America for many years – the wealthy Welsh rarely make their fortunes in Wales – he holds both British and American citizenship.

His book closes with a broadside against Trump and his attack on American values, and the rise of anti-Semitism in the world.

Moritz reveals he has gained German citizenship, to which he is entitled, as a possible safeguard, not without irony of course, against tyranny and prejudice.

So far as I’m aware, there’s no record of how many Holocaust survivors came to Wales or how many people live here now who would otherwise never have been born.

Wales plc seems inexplicably incurious about its Jewish community; one of our museums should consider developing a permanent exhibition and archive. There must be an abundance of family photographs and artefacts looking for a long-term home.

Moritz began working life as a journalist for Time magazine and he is an exceptionally good writer. If you’re not moved by this book, you have the hardest of hearts.

Its emotional impact is heightened by the leanness of his style. Adjectives are rationed, purple prose is banned, and any emotion is conveyed by the facts.

The book is beautifully produced and a pleasure to handle, with crystal-clear photographs on excellent quality paper.

This book deals with some very large issues and an under-examined corner of Wales’ experience too. I can’t recommend it too highly.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

I was born in Vienna in 1936 graduated from Cardiff High School for Girls in 1955, UCNW Bangor in in 1958 and have been in the US since then. I I was not aware of anti-semitism at that excellent school