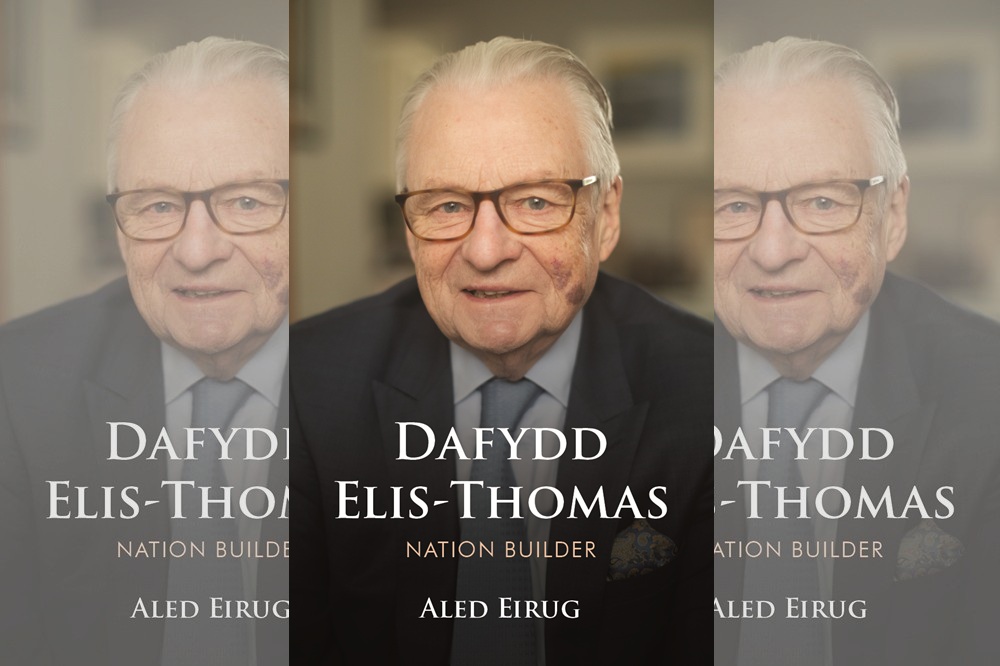

Book review: Dafydd Elis-Thomas: Nation Builder by Aled Eirug

Desmond Clifford

If Plaid Cymru is in government after next year’s election, Dafydd Elis-Thomas will be among those to whom the party owes a debt of gratitude.

Plaid was formed a hundred years ago and for decades rendered itself unelectable as a Wales-wide force. By the time Gwynfor Evans stood down after nearly half a century as leader, he left behind a quixotic, introverted and somewhat cultish movement.

In the 1980s Dafydd Elis-Thomas and Dafydd Wigley, supported by others, set about modernising Plaid Cymru, shaping something like a national agenda with broad potential appeal.

Plaid was well-served by the two talented Dafydds. They were political chalk and cheese but, between them, cast a net widely; Elis-Thomas establishing left-wing credentials, appealing to minorities, English speakers, urban, ethnic communities, gays; while Wigley projected mainstream centrist values and spoke the language of business, aspiration and social solidity.

Spadework

Immediate electoral rewards were scant but their strained and sometimes pained partnership, well documented by author Aled Eirug, did the spadework which helped make Plaid fit to compete for power when devolution eventually arrived.

Elis-Thomas, a son of the manse, was a prodigy, super-clever, bred for high achievement and burdened with expectation.

It’s tempting to feel that his sense of political entitlement combined with an almost pathological determination to cut against the grain was the product of the hot-housing effect of his upbringing and his community’s pressure to be someone.

Anonymity and comfortable humdrum were never real options.

After Bangor University he was destined for an academic career. He had just taken up a post in Bangor when he won Meirionnydd for Plaid Cymru at the first 1974 election, a seat he held, with boundary changes, until he stood down in 1992.

At 27 years old he carried the curse of “Baby of the House”, an invitation to act as enfant terrible which he didn’t ignore. His life was tough enough; a long and difficult journey to/from Westminster, and a young family combined with campaigning travel across Wales.

While Elis-Thomas was profoundly shaped by his community he was determined not to be imprisoned by it and rejected the politics of grievance and exclusivity.

New Left

He made friends in the Labour Party, established the New Left as a group to nudge Plaid leftwards, instinctively seeing that the party had to appeal in the south-east if it was serious about power. Even in those early days, as Eirug describes, Elis-Thomas felt uncomfortable with nationalism as traditionally expressed by Plaid Cymru – an obvious infelicity for an MP in a nationalist party.

Elis-Thomas was not fully formed when he went to Westminster. He began life as an anti-European, bizarrely since “Wales in Europe” came to define his later politics.

Wigley was clear-sighted on Europe from the outset and saved Plaid from a blind-alley.

Elis-Thomas became alienated from Gwynfor Evans, awkward given Gwynfor’s semi-divine status among some. Elis-Thomas thought Gwynfor’s threatened hunger-strike on the S4C issue was an indulgent distraction which held Plaid’s political progress back years.

The 1970s/80s were turbulent. Economic gloom, the collapse of industry, the Miners’ Strike, Meibion Glyndwr, language protest, the Falklands War, Europe, Thatcher; it was difficult terrain for Plaid to negotiate.

The devolution referendum of 1979 was disastrous. Plaid had been luke-warm about supporting it at all because of the weakness of the proposals. When they did, they found Welsh Labour MPs, Neil Kinnock most prominently, campaigning against their own government’s policy.

It was a painful experience for Plaid, and hard lessons were learned. Eirug gives a good account of this era and its complex forgotten battles.

On page 197, the author reports Tony Blair coming to Cardiff on the day of the referendum count in 1997 “in order to publicly celebrate the result.”

Building site

Actually, he didn’t. The Labour Party set up a celebration outside the city hall, which took place in pouring rain, but Blair opted out of coming because the result was so close. He spoke to Ron Davies by phone. Ron was on the roof of the Hilton Hotel, then a building site; I know because Downing St called on my phone (I worked for the Welsh Office at this point) which I handed to Ron Davies when Blair came on the line.

Eirug correctly lauds Rachel Lomax as an impressive Welsh Office Permanent Secretary and a strong support for Ron Davies, but strikes a jarring note when he describes her as “Davies’s trusted lieutenant”;

Lomax was robustly independent and no one’s lieutenant!

The author is unfair about her successor, Jon Shortridge, describing him as “less enthusiastic” in his commitment to devolution. Shortridge was a very different character to Lomax, lower key for sure, but there’s no basis for questioning his commitment.

He’s dismissed as “a town planner from Shrewsbury”. Again, unfair in its implication. The outstanding Lomax worked in Wales for around three years in her entire career and the remainder in London – and nothing wrong with that; Shortridge worked conscientiously for 25 years plus for the Welsh Office and the National Assembly, so the implication of half-heartedness is mean-spirited and unfounded.

Elis-Thomas and Shortridge had a poor relationship, and no doubt this is what Aled Eirug is reflecting.

Civil service

Elis-Thomas was elected Llywydd in the Assembly – he was by far the best choice – and set about trying to correct a constitutionally daft arrangement where both the Llywydd and the Welsh Government took advice from the same civil service.

Since the First Minister (I’m using today’s titles for clarity) was in political charge of the civil service, this greatly compromised the Llywydd’s capacity to act independently.

Elis-Thomas was right to oppose this and demanded change, successfully in the end. It was one of his major lasting achievements. However, Eirug presents Shortridge as deliberately obstructive, unfairly in my view.

Elis-Thomas was right on the central argument, but little effort is made to see things from Shortridge’s viewpoint. He was a civil servant, not a free agent, it was his job to take instructions from the First Minister and to implement the law as he understood it.

This was the essence of the problem; he couldn’t serve two masters with separate and sometimes conflicting responsibilities, and that’s why the original devolution model couldn’t work.

Elis-Thomas leaked correspondence undermining Shortridge to the media – a rotten thing to do since he knew that Shortridge, as a civil servant, couldn’t defend himself against political attack.

As First Minister, Rhodri Morgan, to his credit, provided proper public defence of his official, as Eirug accurately records.

Elis-Thomas’s association with Plaid Cymru can be divided into two parts, his service as a Westminster MP 1974-92, and his service in the Senedd from 1999.

It seems clear now that the Westminster period represented his primary constructive contribution. For all his shifting opinions, free-lancing and policy contortions – as Plaid institutionally saw it – he remained focussed on the bigger picture and essentially loyal to Plaid.

By the time devolution arrived, his politics were more ambiguous. He was the natural choice as Llywydd and excelled in the role over three successive terms.

He exerted a combination of charm, authority and sophistication and give gravitas to the institution.

He handled the demise of Alun Michael with firmness and clear-sightedness.

Senedd building

Working with Finance Minister Edwina Hart, their combined determination ensured that the Senedd building was constructed and paid for (though the account here underplays the part of Ron Davies who, before devolution began, had secured the land and commissioned the design competition which produced the Richard Rogers blueprint – all the incoming Assembly had to do was build it, which was nearly fluffed thanks to Rhodri Morgan’s blind spot about it).

Dafydd’s long and successful stint as Llywydd masked the widening trench between him and Plaid.

When he stepped down from the role, he became an unhappy member of the Plaid group, semi-detached and difficult. Some supporters (in Plaid) thought it would have been better had he ended his political career when he finished as Llywydd.

He left Plaid altogether in 2016, ostensibly in protest at their decision to nominate Leanne Woods for First Minister with the support of the Conservatives and UKiP (it was certainly a bizarre position; was Plaid proposing to run a coalition with UKip?!).

Elis-Thomas became an Independent, arguably formalising what he had long been in any case, and eventually joined Carwyn Jones’ administration as Culture and Tourism Minister, a role for which he was admirably suited.

He was a good minister, properly cultured, liked by ministerial colleagues, respected in the sector and popular with officials – though some felt he could be a little dismissive; a charge which would have surprised few of his erstwhile Plaid colleagues.

Although a successful minister, it seems sad that his long career finished outside Plaid Cymru, the party to which he gave so much, and which gave him his status and platform.

Some former supporters, who had backed him through difficult periods in his life, felt a sense of betrayal. His sister, it seems, was among those who felt alienated by his political journey.

“Dafydd El”, as he was universally known, was certainly among the major figures of modern Welsh politics, keeping the cause alive at Westminster during the bleak 1980s and bridging into devolution in the 21st century.

Alongside Rhodri Morgan, he was the powerful personality of devolution’s first generation and left his mark on the institution.

Complex

His politics were complex and increasingly opaque. He was a non-nationalist nationalist, and if he was elliptical on the independence question, he failed to explain – at least in layman’s terms – quite what model he had in mind.

He spoke engagingly about the “Tudor settlement” but struggled, or avoided, translating this into the practical politics of today.

He was a man of immense charm and, in a way, maybe this was part of his problem; it meant he got away with a lot and he felt, perhaps, that he could push boundaries a little further, and a little more often, than he should.

He was at times genuinely courageous, for example moving the writ for the by-election won by Irish hunger-striker Bobby Sands in 1981. He rarely lacked conviction even if his policy swings could confuse.

I attended Dafydd’s funeral at Llandaff Cathedral in March along with around 1,000 other people. It was the closest thing to a state funeral that a non-sovereign Wales can currently offer, with two Archbishops officiating in the presence of three First Minsters and his successors as Llywydd. The author Aled Eirug gave the funeral address.

Aled explains in his preface his long and close friendship with Elis-Thomas. Dafydd had always rejected the idea of writing a memoir – strangely, for a man with such literary acumen.

Perhaps there were truths he preferred not to confront. Sadly, he never got to read Aled’s book because of his untimely death.

A test for the author was whether he could provide enough perspective and critical judgement on his close friend to avoid hagiography. For the most part he is even-handed.

He sought out Dafydd’s critics (sadly, all in Plaid; he was held in high affection elsewhere) and gives them fair rein. The book is well-researched and well-written, the picture presented is balanced and captures both its subject’s capacity to frustrate and his rare talents.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.