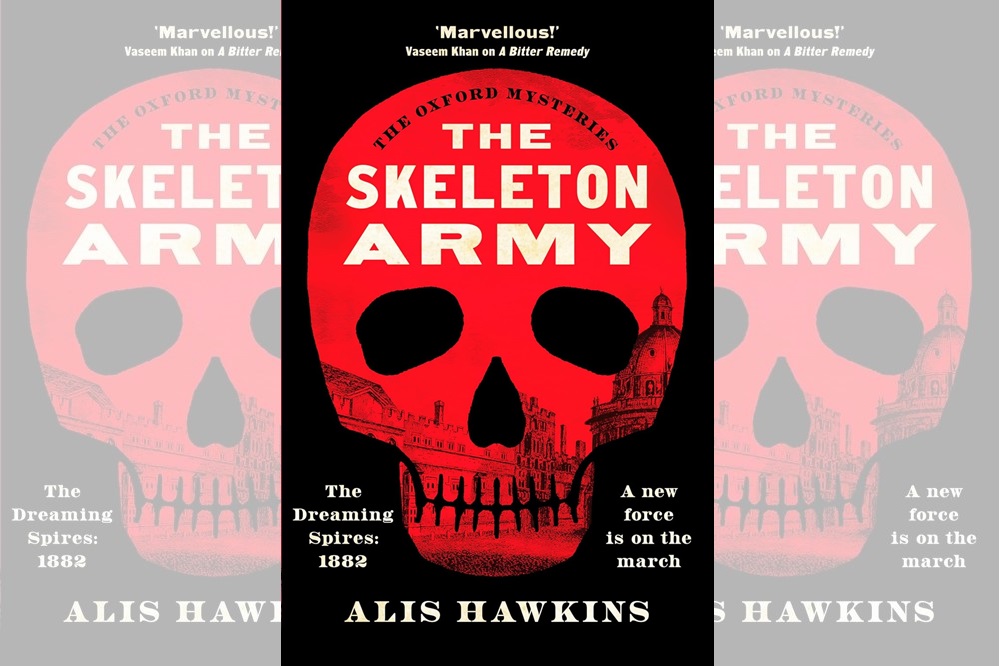

Book review: The Skeleton Army by Alys Hawkins

Myfanwy Alexander

As a lover both of history and novels, I have high expectations of all stories set in the past.

Recently, however, I have observed a depressing trend, whereby though research has diligently been undertaken, the writer totally fails to establish any sense that the inner life of characters living in the past might be radically different from the average attendee at a North London dinner party in 2024.

This tendency has become so widespread that I had almost begun to wonder if historical novel with psychological integrity had mysteriously become unwritable.

Then I remembered Alis Hawkins.

The Skeleton Army, which is the second in Hawkins’ Oxford Mysteries is, if anything, even more successful than the first, A Bitter Remedy.

We have come to expect a cleverly plotted mystery from Hawkins, a story with more twists that the staircase of an Oxford College but in this second novel, she broadens her scope, bringing in Town as well as Gown to a greater extent.

In A Bitter Remedy, the Oxford outside the walls was something of a dangerous backdrop, not unlike the Wild Wood in The Wind in the Willows, but here the relationship between the two parts of the city is explored in a political and religious context which gives a dynamic richness to the story.

Salvation Army

The context for the investigation of the murder which forms the heart of the story is the arrival of the Salvation Army in Oxford and its opposition by an organised gang of thugs funded by the brewers.

It is a sign of Hawkins’ confident familiarity with this period that she doesn’t shy away from placing at the centre of her story one of the aspects of Victorian life which seems furthest from modern sensibilities, the temperance movement.

This response to what was perceived as one of the greatest ills of industrial Britain is now seen as at best Quixotic and at worse ludicrous, but Hawkins’ story makes the reader understand exactly the conditions which spawned responses such as the Salvationist crusade against alcohol.

We tend to regard the lives of unremitting misery experienced by the Victorian poor as only able to be remedied by political change, but Hawkins skilfully invites us to consider that the notion of self-help provided an avenue for self-improvement though, as the story unfolds, the individual conversion of the head of the family might not always lead to redemption for all concerned.

And when the thugs known as the Skeleton Army start to attack the Salvation Army on the street, blood will flow.

Engaging

The novel is told from the point of view of two clearly drawn and engaging characters, Non Vaughan and Basil Rice.

Throughout the novel, Non, who is about to sit her final exams, struggles to find exactly the right direction to follow: she wants to create a more equal world but struggles to compromise.

She is a sharp study in youthful idealism and her agonizing about her own path contrast with her decisive detective work.

Non’s slow realization of the nature of her feelings towards a fellow undergraduate is delineated with almost Austenian lightness and provides another example of Hawkins’ ability to create characters who are of the age they rebel against: her protagonist does not lean in and whisper in her dance partner’s ear ‘let’s get it on, big boy,’ which is the sort of anachronism which has had me hurling historical novels across the room lately.

Emotionally bereft

Basil, an academic, is tormented by his inability to follow his heart: his former lover has married, leaving Basil not only emotionally bereft but without any outlet for the passions Wilde described as ‘the love that dares not speak its name.’

There is no leaden point-making here: Hawkins leaves her readers to decide about the cruelty of a society which does not allow Basil to love freely and in so doing, delivers her message in an emotional rather than a didactic mode.

The themes of inequality, forbidden love and personal responsibility weave through a fast-paced narrative in which the location plays a key part.

A reader not familiar with the geography of Oxford does not need to know how far Jesus is from the Sheldonian to enjoy the book and the crisis of the story, which occurs in Commem Week, has a background of a series of colourful events which are thoroughly explained.

But perhaps the very best way to enjoy The Skeleton Army is to pack it in your picnic basket as read it as you are punted along the Isis by a willing companion.

The Skeleton Army by Alys Hawkins is published by Canelo and available from good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.