Breathing fire: The making of The Dragon Has Two Tongues

Christopher Evans

The revolutionary and ground-breaking Welsh history series The Dragon Has Two Tongues recently re-emerged online. Its resurrection has reignited interest in the magnum opus of legendary Welsh director Colin Thomas.

Examining and dissecting Welsh history from two contrasting views, ‘The Dragon’ changed the conventional and accepted perceptions of Wales and its past.

Produced by HTV for Channel 4, the 13-part series, which first aired in 1985, took an unconventional approach to traditional documentary filmmaking through the use of two presenters.

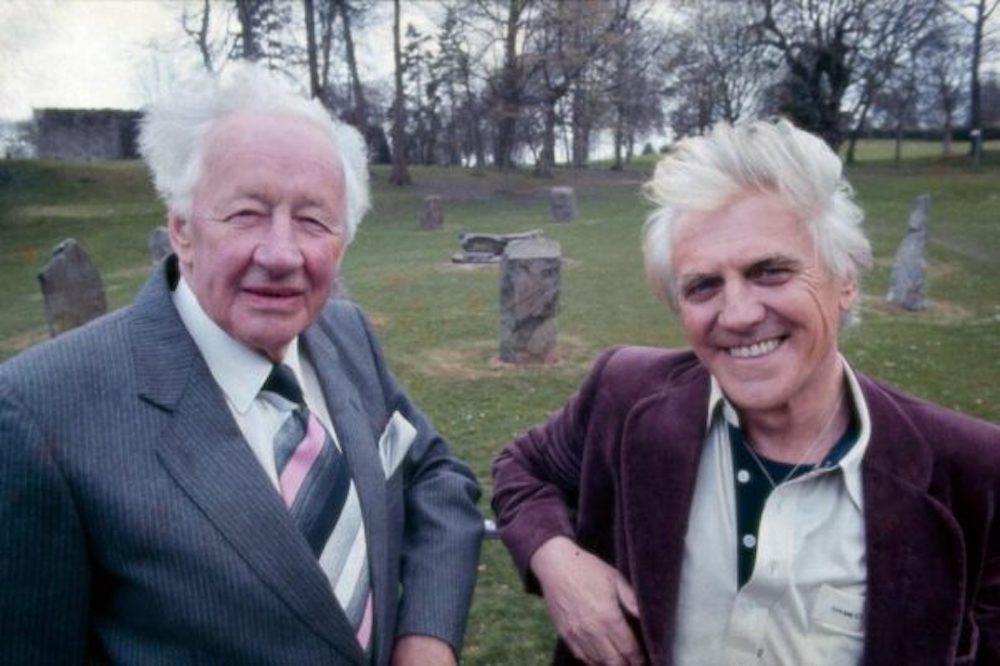

This allowed history to be explored and scrutinized from the opposing views of the conservative Wynford Vaughan-Thomas, and the Marxist firebrand Gwyn Alf Williams, both distinguished historians.

Director and producer of ‘The Dragon’ Colin Thomas says that he is “so proud of the way it has resonated with people in a way that I had never expected at the time.”

Early Years

Born in Carmarthen in 1939, the 83-year-old Thomas’ family moved to Cardiff when he was a boy.

Thomas attended Cathays Grammar School and developed an interest in film from a young age.

A socialist, he studied English and Political Intuitions at Keele University, which he says, “had this sort of lefty tinge to it, as it was the only university funded by the 1945-51 Labour Government.”

Following his graduation, Thomas applied for a traineeship at the BBC.

“I’d always been interested in film and had produced plays prior to joining the BBC in 1962. I was very inspired by Raymond Williams’ book ‘On Culture and Society’, which came out in paperback on penguin in my last year of university. I dug up my copy recently and there were certain sections of it heavily underlined. That one was of the motivations for me, it fired me up and influenced me a lot. It was the logical next step.”

Resigning from the BBC

Whilst working on ‘City on the Border’ (1978), a documentary about the troubles in Derry/Londonderry, Thomas’ burgeoning BBC career came to an abrupt end.

“There were 3 directors (Colin Rose and Philip Donnellan) for the programme. Each of us filmed with different groups for a week. Mainly the British Army, Protestants and Catholics.

I don’t think all three of us were particularly happy with the end product, but we delivered it anyway. To our astonishment, or at least my astonishment anyway, we were told it was not acceptable.

Usually in the BBC, there would be a bit of a negotiation and you could have a conversation about the content. You know, ‘amend this, concede on this, possibly lose that’. But this was absolutely clear, ‘this sequence must be removed!’.

The sequence in question that was “the crunch point” for Thomas was of a mother tending to the grave of her son. The camera pans to the headstone which reads:

‘In Loving Memory of Our Dear Son, Michael Gerald Kelly, Aged 17 Years, Murdered by British Paratroopers on Bloody Sunday, 30 Jan 1972.’

“When I was told to remove the entire sequence I just thought ‘I’m off, I’ve had enough’. I resigned from the BBC there and then. In retrospect, I had been becoming increasingly unhappy about things that I was required to do at the BBC.”

Temporarily unemployed, Thomas soon found short contracts with the Irish television station RTÉ. After a few months he left Dublin to return to the UK, where he found work initially hard to come by.

“Then Channel 4 and S4C started. Suddenly, the whole context changed.”

The Dragon Has Two Tongues

After directing a programme for ITV about the disgraced former Swansea council leader Gerald Murphy, Thomas’ status was enhanced leading to an offer that would change his career trajectory.

“I think I was just in the right place, at the right time. When Channel 4 agreed to commission a history of Wales from HTV, HTV then approached me and offered me the job of producing and directing the programme.”

Originally planned to be solely presented by Wynford Vaughan-Thomas, it was soon clear to Thomas that something different was necessary if the show was to be a success.

“Wynford was the head or controller of programmes at HTV, I can’t quite remember his exact title. We had a few discussions and I soon realised that his perception of Welsh history was quite different from mine.

I suggested to Wynford that we have a female historian as well as him. He didn’t like the idea at all (sighs). He met Angela John and was so hostile to her and the whole notion of a two-presenter approach. She decided that it would just be too unpleasant working with him for what was probably at least two years, and so she pulled out, quite understandably.”

Thomas persisted, knowing that for the show to work and be engaging, another presenter was needed.

“I kept trying to persuade Wynford, so I introduced him to Gwyn Alf Williams, who I had long admired both as a historian and lecturer and whose work I thought very highly of.

When the two of them met they actually got on really well. They both reminisced about the Second World War. Gwyn had been a solider and Wynford was a War Correspondent, so it got off on a really good footing. Although Wynford wasn’t enthusiastic about the two-presenter idea, he finally agreed to go along with it in the end as he liked Gwyn.”

Thomas says that although Vaughan-Thomas was a traditionalist, he was experienced enough to realise that it was a different and innovative way of doing things.

“I knew it was going to be innovative, and that was the great thing about Channel 4. Certainly, had I proposed that idea to the BBC, I don’t think they would have considered it, quite honestly. But Channel 4’s whole brief was to be cutting-edge and innovative. And they saw themselves, initially anyway, as publishers. We, as producers and directors, were the authors. It was such a different way of doing what I was used to at the BBC.”

Content of ‘The Dragon’

Deciding on the content for the entire history of a nation was a challenge, particularly with Wales having such a rich, tumultuous, and often not well-known, some would say hidden, past.

“Wynford had initially drafted out a 13-part series right from the beginning, but I shifted it substantially more to the present.

We had recorded meetings with Wynford, Gwyn Alf and Medwen Roberts, who was a very good researcher and was Welsh speaking. She made sure we didn’t lose sight of the Welsh language perspective.

I wanted less programmes on the past, more on the present. A friend of mine who was doing the history of Ireland said to me ‘oh, you’ve got 13 episodes, why don’t you do three pre-1900 and the rest in this century’. He meant I would have access to archive film and the job would be easier.

But I felt that this would be counter to Welsh history. I decided to include animation segments which was a way of maintaining the visual interest, which is always a problem for television history. The four of us then re-drafted it and you could see in those conversations what the lines of arguments were going to be in each episode.”

With the support of HTV’s Education Officer Bethan Eames, viewing groups were set up across the UK, not just in Wales. Educational document packs for were created in order to support and expand upon each episode of the series.

“The viewing groups had access to these document packs. The idea was that if people were stimulated by the arguments between Wynford and Gwyn, they could go back to primary sources and original documents whenever possible. I wanted people to think ‘let’s go back to the source and make our own decisions. You know, we might disagree with both of them, we might agree with Gwyn here, or Wynford there’. It enabled them to go back to those primary sources.”

When quizzed about the possibility of the content of ‘The Dragon’ being on the Welsh curriculum, Thomas is reticent.

“Well there has been ‘The Story of Wales’ since then, of course. I mean, I have my criticisms about that, but I don’t want to…how old is ‘The Dragon’ now? 1985…it’s probably dated a bit. I have heard people suggest and argue for it to be shown in schools, but I don’t really want to get involved or upset the people involved in ‘The Story of Wales’.

Filming and hopes for ‘The Dragon’

Although nervous about how the series would be received, Thomas says that the longer that it went on, the more confident he became that it would be a success.

“I was worried right up until the moment we finished it. But by the time we started editing it and senior people from HTV were coming in, I began to think ‘oh, this is going to work’.

With a healthy budget, ‘The Dragon’s’ innovation was enhanced through animation scenes, something that was expensive and new at the time. Thomas says this “brought the history to life in a way that a drawing or picture couldn’t.” He laughs when talking about having the presenters filming on location in a helicopter. “I can’t complain, HTV let me do what I wanted!”

Filming wasn’t always straightforward, sometimes to Thomas’ despair, as the passionate and confrontational presenters would often want to ensure that they had the last word.

“What tended to happen was that the arguments got more intense the closer we got to the present. For instance, Gwyn would do a piece about the 1930’s and he would talk about the unemployed workers movement. It was a very powerful piece and is in the programme. Then I would say to Wynford, ‘well, Gwyn has done a piece about this…’

Wynford would say ‘an unemployed workers movement? I was working in the Rhondda in that period and I’ve never heard of it! I’ve got to do a piece to camera countering that!’

Then I would record a piece with him. He was involved in a benefit organisation that was helping the unemployed in that period, so he recorded a piece giving his perspective on unemployment in the 30’s.

I would go back go Gwyn and tell him that Wynford had done a piece that the unemployed workers movement was of no significance. Outraged, Gwyn would be like (put’s on brilliant Gwyn impression) ‘WHAT?! I’ve got to do something countering that’, and it became a bit of a nightmare (laughs).

I’d be saying ‘Gwyn we have got to get it all into 28 minutes you know, I can’t go on endlessly (laughs). Those were the sort of problems I had when filming!”

Tensions

Tensions could also spill over after filming, with one incident in particular etched into Thomas’ memory.

“We edited all 13 programmes first without the dialogue scenes. All the dialogue, all the confrontations between the two presenters, all happened right at the end. We went on a tour of Wales at the end doing them in the different locations. It was going reasonably well, although it could sometimes be a bit acrimonious. Usually what I did was show them the programme as edited without the dialogue, without the confrontation, and then set them off!

On this particular occasion we were at Aberystwyth University. We were going to do a dialogue piece to camera early the next morning, so we showed them it the night before. They had both had a couple of drinks (laughs) and they watched the programme. I could feel Wynford getting more and more irritated as we were watching it.

He started muttering ‘Oh God, more of this Marxist claptrap’, and Gwyn hearing him just suddenly exploded (imitates Gwyn shouting), ‘I have to put up with your reactionary bullshit Wynford, for God’s sake!’ and he stormed out of the hotel.

I rushed after him to try and pacify him. Gwyn was not to be pacified and headed off to another pub. I came back and then Wynford was annoyed with me for trying to pacify Gwyn! He felt he was the one who should be appeased. I thought ‘oh god the whole thing is going to fall apart.’ I had a sleepless night worrying about it.

I came down for breakfast in the morning and Wynford was tucking into his bacon and eggs. Gwyn came up and knelt at his table. He took Wynford’s hand, kissed it, and apologised (laughs). It was all resolved, and we were back on again!”

‘The Dragon’ was well-received by viewers and critics alike, with even the UK National newspapers giving it favourable reviews. Thomas says he was relieved, particularly as he thought it may only appeal to a Welsh audience. “I think that the two-presenter approach raised issues about history, historiography, as it were, rather than just about the specific concerns of Wales. It raised issues of how the same events could be interpreted in a different way.”

Legacy

Nearly 40 years on, Thomas is surprised by ‘The Dragon’s’ continued influence. He thinks one of the reasons for its continued popularity may be due to its unconventional approach to history.

“I had read a pamphlet produced by the BFI called ‘Television and History’. It’s by Colin McArthur. He criticises most television history programmes for more or less saying that ‘this is the truth about the past’. The idea that there is ‘the truth’ – that is what I wanted to grapple with above all, to open it up and say there are differences. You might agree about the fact of what happened, but you can disagree fundamentally about the interpretation of those facts. And that is a really important point to get over about history. I think that is part of what made it so influential. And Gwyn, of course.”

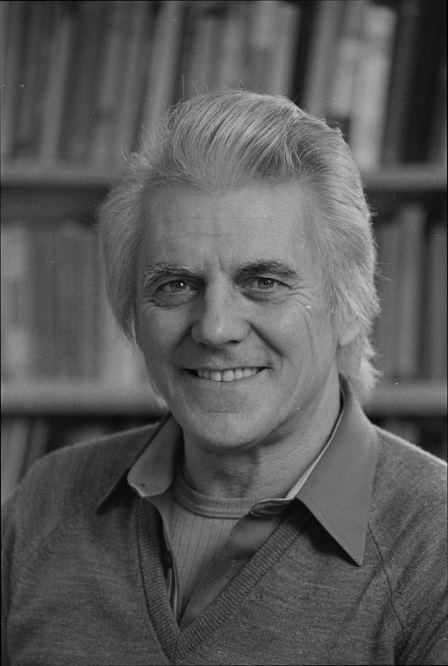

Gwyn Alf Williams

Legendary historian and television presenter Gwyn Alf Williams on ‘The Dragon Has Two Tongues’

The effervescent and captivating presentation skills of the late, great Gwyn Alf Williams played a huge part in the success of the programme.

“I always admired Gwyn’s way of communicating. He could shift even an academic journal into the language of ordinary people. He managed to break out of that dreadful academic jargon that sometimes clogs up communications by academic historians. He could get out of that and yet still be sound and solid about his history.

Gwyn was such a wonderful television presenter. I think his excitement and imagination came over so powerfully.

Thomas’ voice cracks slightly as he remembers his old colleague, and most importantly, friend.

“In the end we made twenty-nine programmes together. He was a joy to work with. I mean, sometimes very difficult, but mostly it was wonderful. I’m emotional just talking about him. He became a close friend. I loved him. He was a lovely man. I can tell you, we did have some terrible arguments and ups and downs, less so in ‘The Dragon’, but later on. But he was such a wonderful man and I miss him.”

Whilst talking about his late friend a memory is triggered that sums up the wit of the late historian.

“I had tried to get Gwyn and Wynford to do a joint book to coincide with the programme, but they wouldn’t have it. They both wrote books on Welsh history. At the end of filming, Gwyn gave a signed copy of his book ‘When was Wales?’ to Wynford. He had written in it ‘to my beloved enemy’ (laughs).

The Future

When asked about a possible remake or return of ‘The Dragon’, Thomas chuckles. “I’m 83! Those days are long over!”

However, the evergreen Thomas is still working, most recently promoting a number of events around Wales entitled: ‘Putting Wales On Television – S4C and Channel 4: The first 10 years.’

“I see it as a way as defending public service broadcasting, which is under attack by this government. The idea is to remind us of what those channels have contributed, which is fantastic. You could push boundaries, do new things, be innovative. It’s a reminder of what was achieved during those years.”

Thomas’ documentary Hughesovka and the New Russia (1991), again presented by Gwyn Alf Williams, won him a BAFTA-Cymru, but he is adamant ‘The Dragon Has Two Tongues’ is the peak of his oeuvre.

“It has resonated and stayed in people’s minds. I never envisaged that. You know, the nature of most television is here today, gone tomorrow. To see it come back to life again has been really heartening.”

A revolutionary both on and off screen, Colin Thomas’ creativity and intelligence continues to bring history to life.

Colin has also created a free app on the history of Welsh film and television, co-authored by Colin and Iola Baines, it is entitled “Picturing Our Past/Fframio’n Gorffennol”.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Another great piece from N.C’s Culture page…

Gwyn’s smile is contagious, it brightened my gloomy morning no end, bless him…

When I was a Hanes Cymru student years ago my tutor wanted to show us The Dragon Has Two Tongues but HTV wanted so much money the dept. said it was beyond their budget…

On reflection I think that was a form of Anti-Marxist Claptrap censorship on HTV’s part.

“s it was the only university funded by the 1945-51 Labour Government.” Incorrect! Harold Wilson’s Labour Govt, surely?

Was it not the Open University that Wilson founded…’the white heat of technology’…You could have mentioned “Political Intuitions”?

‘The Dragon has Two Tongues’ was a milestone and had a very original format that worked successfully, namely the two-pronged thesis and antithesis approach. It should certainly be made available to all secondary schools in Wales.

A friend told me, incidentally, that Wynford Vaughan Thomas was in reality a little more sympathetic to some of the interpretations presented by socialist firebrand Gwyn Alf Williams than the programme leads us to believe; but the format of the series required two contradictory points of view.