Carmarthenshire’s Politician-Novelist

Adam Pearce

The idea of a Politician having written a novel in their earlier years is nothing too unusual these days—who remembers Boris Johnson’s cringeworthy Seventy-Two Virgins?—but the idea that a politician’s novels could actually have a small but important place in the literature of a nation—surely not?

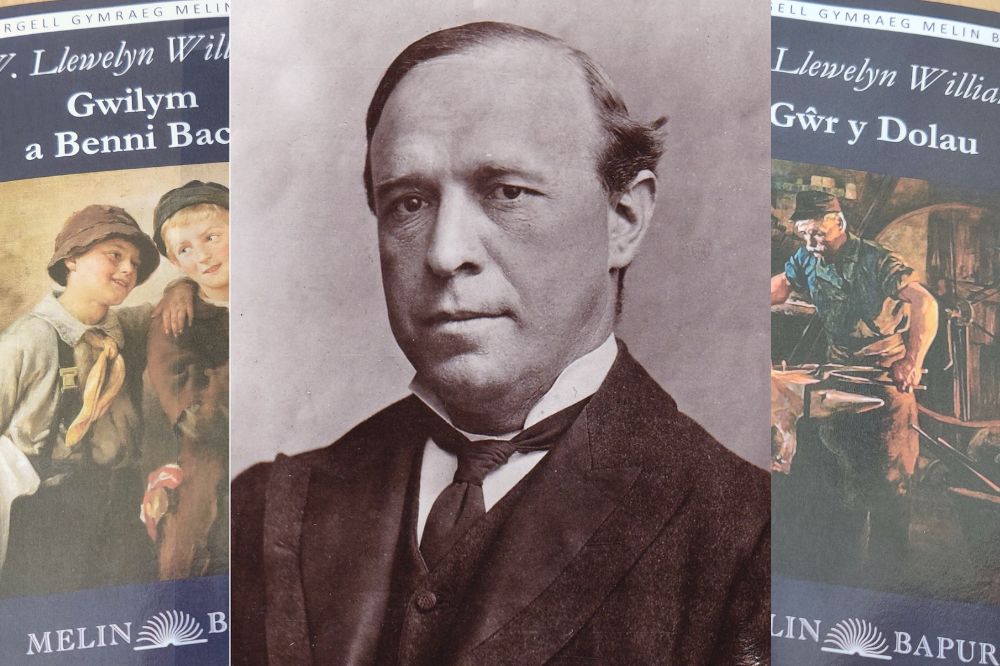

Well, here in Wales, there was one who did. William Llewelyn Williams’s (1867-1922) entry in the history books will doubtless focus on his twelve years as the Liberal Member of Parliament for Carmarthen Boroughs from 1906-1918, and his role in the decade before that as part of the early nationalist Cymru Fydd movement, of which he would found the first branch in the south of Wales.

The son of fairly well-off middle-class parents in the Tywi valley, Williams had the good fortune to take advantage of an Oxford education, perhaps uniquely among the Welsh novelists of the nineteenth century.

As a member of the radical nationalist wing of the Liberal party he was initially a major ally of Lloyd George, though later would very publicly fall out with him over the issue of the First World War, which Williams opposed, going on to stand against George’s preferred candidate in the 1921 by-election in Ceredigion.

“Bona fide classic”

But his literary legacy, small as it is, is perhaps the main reason Williams deserves recognition in the twenty-first century. During his time as a journalist in 1890s he completed two novels—at least one of which is a bona fide classic—which we at Melin Bapur are very pleased to bring back into print.

The first of these, 1894’s Gwilym a Benni Bach, is something of a student effort—here is a novelist still working out his craft—but within its limited scope and allowing for its short length it is a charming little work.

Structured as the memoirs of a young doctor visiting his nephews, the book has very little plot, being more of a series of scenes with the same characters tied up with a lovely happy ending; one could very easily bill the work as a series of short stories rather than a novel.

Right from this start though we see some of the author’s strengths in evidence, strengths which would come to fuller fruition in his second novel: specifically his lively dialogue (mainly in wonderfully realised Carmarthenshire dialect) and his use of humour, which prevents the story ever from skipping into mere kitsch by ensuring the reader is never allowed to take things too seriously.

Not to say that there is nothing more serious about the book, though: of particular note is a scene early on where a rebellious child stages a school rebellion against the Welsh-not wielding schoolteacher.

The scene is played for laughs, and it is a funny scene; but beneath the humour is a clear undercurrent of social commentary: how can we, Williams seems to ask, as Welsh parents allow this abuse of our own children?

As Dafydd Jenkins identified it is a book about children, not for children, and in this respect it is the definite predecessor of later, better known works about children by Welsh authors like Kate Roberts’ Te yn y Grug.

R. T. Jenkins correctly identified that with Gwilym a Benni Bach Williams had repurposed the plot of an English novel, Helen’s Babies by the American John Habberton; but beyond the basic premise the two works share very little: Gwilym a Benni Bach is not any kind of translation or adaptation and is very much a novel of its place.

It is a very short and straightforward work that may well appeal to those taking a first step in the literature of this period, or those learning the language: something of a Stori Sydyn for the 1890s.

Ambitious work

Williams’ second novel, Gŵr y Dolau, which first appeared as a serial in 1898, is an altogether more ambitious work, and harder to define.

Although set in the same village as the first novel, we are following a different and larger cast of characters, adults this time.

To the extent that Gŵr y Dolau can be said to belong to any genre at all, it is a temperance novel—a late example thereof—in that we see Dafi Jones, the titular owner of the farm Dolau Gwynion, meet his downfall due to his inability to control his drinking.

If this sounds tedious and a turnoff, don’t worry though, because we spend very little time in chapel or bar-room either and for most of the story we see little of Dafi Jones at all and instead spend our time with other, more interesting characters, like the mischievous blacksmith Nat and the pompous but insecure poet Robin o’r Llwyn.

This simple fact exemplifies the novel’s obvious flaw: the lack of obvious direction to the plot. The prologue and the first chapter set up Dafi’s arc, but it is then abandoned for most of the novel, to be picked up again only towards the end.

There is almost a sense that these are a series of interconnected scenes rather than a properly structured novel. This is the same issue from which Gwilym a Benni Bach suffers, but it is more obvious here because of the larger canvas; it robs Dafi’s arc of much of its impact, making his sudden deterioration at the end feel unconvincing even by the standards of Victorian novels.

This inability to construct a novel is a flaw Williams inherited from his main influence, Daniel Owen, though fortunately here again Gŵr y Dolau is a short enough work that it ultimately doesn’t matter too much: it is enough for us to simply to spend time with these characters, getting to know and to love them.

And you will want to: because despite this quite serious flaw as a novel, the things that are good about Gŵr y Dolau are so, so good. The prose holds up brilliantly, being extremely fluent and naturalistic, with none of the affectation and pseudo-literariness that afflicts so much writing of the period (in English as much as Welsh).

The comedic scenes are brilliant, equal to anything in Daniel Owen, and Williams has the same talent for character-based humour. Take Robin o’r Llwyn, for example, a brilliant parody of the bardd gwlad: he speaks in an affected literary register, dropping lines of cynghanedd casually into conversation, and constantly seeks the “honest opinion” of others of his work only to blow up in indignation should they offer the slightest criticism.

His services are hired by Rowlands the curate for whom he writes a love poem (to order) to woo Gladys, the object of Rowlands’ affections: Gladys responds in verse, cleverly demolishing both Robin and Rowlands in the ultimate poetic mic-drop.

There are lovely, brilliant switches in tone for comedic effect, like this wonderful passage describing Gladys: Pe gwelsai bardd neu arlunydd hi ben bore yn rhedeg allan i’r clos â phadellaid o geirch yn ei llaw—a’r gwynt nwyfus yn chwarae â’i gwallt ac yn codi gwrid i’w hwyneb… a’i gweld yn bwydo â llaw dirion y fronrhuddyn a’r aderyn y to, ac yn ysgwyd ei ffedog yn wyneb rhyw hwyad daeog neu iâr reibus a’i gyrru ar ffo i’w lle eu hun: pe gwelsai bardd neu arlunydd hyn, meddaf, coronai hi ar unwaith yn Frenhines yr Adar.

Ond nid oedd bardd neu arlunydd yn y Gelli, ac ni thynnodd sylw neb ond Leisa wrth fwydo’r ieir a’r adar. Ac ni ddywedodd Leisa ond hyn:

“Dir safio ni! Garw mor ffond o ffowls mae Miss Bowen.”

Dialect

It’s not just comedy, either. The novel ends with the obligatory deathbed scene—a man laid low by that most deadly of Victorian afflictions: narrative justice—probably intended to be the emotional climax of the novel.

But this moment in fact comes a couple of chapters earlier, when, summoned to a hearing at which he is to be cast out of chapel for his drunkenness, Dafi and his wife take a walk through the forest to the chapel, reminiscing about their earlier courtship: it is such a powerful, understated and beautiful passage and expression of matrimonial love and forgiveness that it elevates the scene well above it’s function within the derivative plot.

Despite its obvious issues it is extremely difficult to read this book and not to like it, and what higher praise can there be?

No discussion of W. Llewelyn Williams’s literary legacy would be complete without a word on his use of Carmarthenshire dialect. Other writers had used dialectical Welsh in their books before, but none so extensively, and none veering so far away from the standard literary form.

It’s a wonderful touch that really roots these novels in Dyffryn Tywi, and the one respect in which Williams really was an innovator and for which he deserves wider recognition.

Using regional dialects of Welsh in fiction is commonplace now—some would argue too common—but this is a tradition which really begins with W. Llewelyn Williams.

All those interested in Welsh dialects will want to read both these novels, as will anyone with an interest in the development of the Welsh novel, or the literary tradition of Sir Gâr!

Importance

Gŵr y Dolau was a popular and critical success—it is a classic in Cymraeg, or at least deserves to be—and Wales might have hoped to have found in W. Llewelyn Williams a worthy successor to Daniel Owen’s crown.

Sadly, it was to be his last novel, as he gave up fiction to pursue his political career full time. One can only speculate what he might have written had he not done so!

Still, whilst they are by no means perfect, the two novels he did write are an important part of our literary tradition, and a worthy addition to any Llyfrgell Gymraeg.

Gwilym a Benni Bach and Gŵr y Dolau are available from www.melinbapur.cymru and priced at £7.99 and £8.99 respectively + P&P.

Bricks & mortar stores interested in stocking Melin Bapur’s books are requested to contact the publisher at [email protected].

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

There is an English novelist who has an even more distinguished than Llewelyn Williams,namely Benjamin Disraeli.

Between ‘distinguished’and ‘than’ please insert ‘career’.