Consuming Welshness: Fetishisation, mysticism, and uninterrupted life

Llinos Anwyl

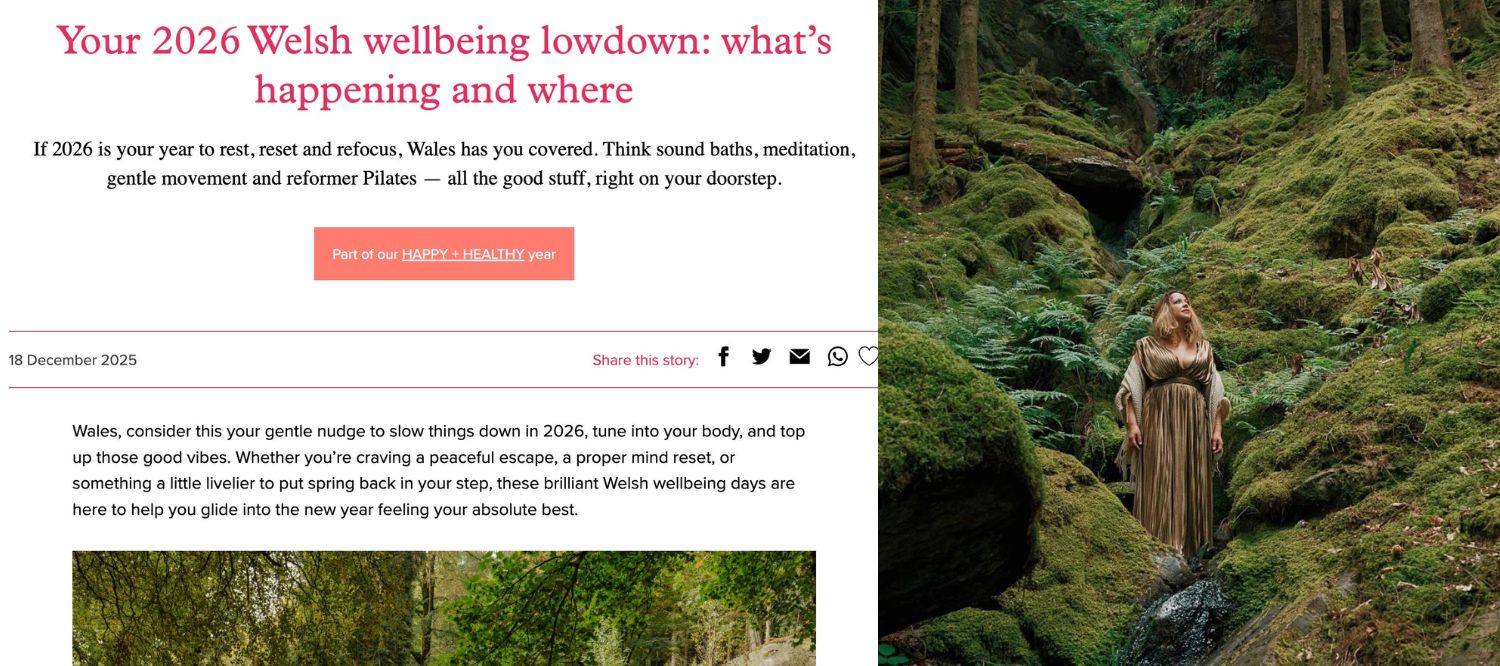

There is a particular way Welshness appears. It tends to arrive as atmosphere. Framed through woodland, ritual, and a promise of depth that never quite reaches the present. Suspended.

This essay is concerned with Welshness as something that is consumed, circulated as an object.

Something coherent, legible, available for appreciation. And how the Welsh language, Cymraeg, sits inside this process not as the main object, but as its guarantor.

Cymraeg secures authenticity while its ordinary use recedes, functioning as texture rather than speech. It’s kept near, stabilising a version of Welshness that reads as timeless, traditional, and just out of step.

In this form, Welshness is something to be sensed rather than entered into. Feeling over use, and a hyperfocus on land and intuition. The relationship between language and land is real. Of course, it matters. Languages grow in place, shaped by geography, labour, memory, and movement. The difficulty is not the connection itself, but what happens when that connection is aestheticised, stripped of social life, and returned as mood. Something you can step into briefly, without having to stay.

Mysticism smooths reality. That is part of its appeal.

The British gaze that encounters Welshness this way did not appear by accident. It is shaped by a longer history in which Wales is positioned as internal other: close enough to be familiar, different enough to be aestheticised. The shift is not away from exploitation, but from production to consumption. Welshness becomes something to be visited and felt. A cozy jumper to be worn.

From that gaze, Welshness is most easily encountered as difference. The most obvious marker of that difference is the language, and this is where fetishisation gathers. Cymraeg signals depth, authenticity, alterity. Its presence lends landscapes an added sense of antiquity, people a presumed closeness to nature. This is where the loose language of the ‘Celtic’ appears. Rarely defined. Widely invoked as atmosphere, not historical facts. The language does not describe the land so much as enchant it.

For those raised within Welsh-speaking communities, this framing doesn’t feel abstract. It lands as displacement. You become an oddity. At the same time, Welshness is offered as a form of wellness. Restorative. Grounding. Land-connected. Learning Welsh is not the issue. My discomfort sits elsewhere, in the sense that Welshness is most visible when it feels curated rather than lived. As if its appeal has been decided in advance, and amplified in place of a contemporary culture that exists.

This version of ‘Welshness’ feels generous and narrowing at the same time. I keep trying to sit comfortably with that, and I can’t. Because the issue is not misrepresentation. It is a mode of attention. A way of being close without consequence. At its core, the problem is this: Welshness is not misunderstood. It is enjoyed in ways that prevent encounter.

Within this structure, the language is present enough to authenticate Welshness, but never active enough to require reply. It secures depth without introducing reciprocity. You can admire it indefinitely without ever having to answer it.

It is useful to think of this relation as parasocial. A one-sided intimacy with an object. Welshness is encountered as something familiar, emotionally charged, even cared for, without any requited relation to the social reality it emerges from. The attachment feels real precisely because it is insulated. It allows projection without consequence. Welshness becomes something people feel they know, while remaining untouched by its mundanity, its politics, or its demands.

What makes this relation so comfortable is that it appears to sit outside politics altogether, offering relief from the present rather than any demand to change it.

I understand the appeal. A gong bath in Charlotte Church’s forest looks deeply relaxing, I won’t lie. Part of me would love to believe that crystals could do my emotional work, because that would be far less effort than unpacking a messy, loaded past with a therapist.

That’s the point. The fantasy promises relief without labour and healing without history.

This is the logic of fetishisation. Not ignorance, but partial knowing. Enough to sustain enjoyment. With no intention to disturb it. The object is preserved so that the relation does not have to change.

Under contemporary capitalism, this kind of soothing difference is actively produced. Cultures are not flattened into sameness, but curated into forms that can be enjoyed without friction. Difference becomes an affective resource: something to feel through, retreat into, and emerge from unchanged. Welshness fits this logic neatly when it is rendered spiritual and timeless.

Welshness is managed through temporal containment, granted atmosphere and history, and therefore denied a future that might make demands.

Much cultural critique in Wales has focused on (mis)representation. On accuracy, respect, tone. That attention has mattered. But fetishisation doesn’t depend on distortion. An identity can be rendered sympathetically, and still be held at a distance.

What matters here isn’t depiction so much as relation: the kinds of approach that are encouraged, and the ones that are quietly closed off, with enjoyment doing much of that work. Ideology functions here not by lying, but by organising what doesn’t have to be confronted. No one is being tricked into thinking Welsh is dead or irrelevant. What’s organised instead is a form of relation that makes confrontation unnecessary.

People often know perfectly well that Cymraeg is a living language used daily. That knowledge doesn’t unsettle the structure. It sits alongside it.

I know very well Welsh is spoken every day, because I spam my friends with messages.

I know very well it is contested, political.

But still, I feel the pull of the version where it appears as mood, ritual, woodland, feeling. Because that version doesn’t look back. And it doesn’t look forward either. Fantasy doesn’t just soothe. It keeps things exactly where they are. What this enjoyment quietly suspends is not only obligation, but implication. The question of who bears responsibility for history, for power, and for the material conditions that would make Welshness something lived rather than merely felt.

Welshness, in this form, becomes something you can care about intensely without it ever asking you to care differently. What’s protected here isn’t Welshness, but the comfort of those who want proximity without response. A living language is inconvenient. It requires reply. The version of Welshness that circulates most smoothly asks for none of this.

What gets lost in all of this is not only political urgency, but social reality. A language does not survive as atmosphere. It survives through use, friction, and repetition. Through being slightly inconvenient. Through being the thing you have to navigate when you’re tired, distracted, irritated, or in a hurry.

Languages do not disappear dramatically. They thin. They lose domains. They are eased out of ordinary situations and confined to places where they can be admired rather than relied upon. The mystified version of Welshness contributes to that thinning, even when it appears supportive. Especially when it appears supportive.

There is a quiet contradiction here. Cymraeg is held up as proof that Welshness is validated in an ancient and deep sense. But the same framing implies that its natural home is elsewhere: in the past, in the landscape, in feeling, in retreat. The language is respected, but not trusted. Valued, but not relied upon.

This is where the othering becomes structural. Welsh speakers are included as custodians of something fragile and special, rather than participants in something ongoing. That inclusion carries an expectation: keep it beautiful, keep it soothing, keep it unthreatening.

When Welshness is curated this way, it becomes easier to celebrate the language while resisting the conditions that would allow it to function fully. Celebration fills the space where responsibility might otherwise appear. This is why inheritance matters. Not whether Welshness is admired, but whether it is allowed to persist as a lived, shared, argumentative, contemporary practice. A culture cannot survive on affection alone. And a language cannot live if it is only ever encountered as a feeling.

My discomfort sits here. Not in land, or care, or spirituality, but in the insistence that Welshness must always arrive reduced to a simplistic sludge.

This discomfort isn’t personal. It’s diagnostic.

Welshness survives, in this frame, as aesthetic and feeling. Practice and presence is elsewhere.

What worries me isn’t simply misrepresentation, but inheritance. If this soft-focus image becomes the most visible trace of Welshness, it begins to function as a record.

Is that all we are meant to be?

A note on fantasy

Some of the questions in this essay are already being worked through elsewhere, in different registers.

Jimmy (The Welsh Viking) a research archaeologist, has been thinking publicly about how Welshness is portrayed in romantasy, and about what gets borrowed, flattened, or aestheticised in the process. Drawing on his background, the video I reference here picks at a question that runs alongside this essay: what does it mean to draw atmosphere, myth, and feeling from living cultures without engaging with the conditions they exist in now?

For readers who want to push the question of fantasy further, this lecture by Slavoj Žižek offers another angle. Speaking on the transcendental constitution of reality, Žižek moves through Freud, Lacan, and Badiou to think about dreams, subjectivity, and fantasy not as escape, but as the structure that makes reality bearable.

It’s dense and occasionally infuriating, but it circles a familiar problem: how fantasy doesn’t distract us from what we know, but organises our relation to it so that nothing has to follow.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

I didn’t enjoy this world salad.

I get the sentiment but who cares if Welshness is aestheticised and commodified? If this stuff didn’t exist the void would be filled by even more generic Anglo-American guff.

Rydw i’n cael trafferthion mawr gyda’r erthygl yma. Efallai fod hynny â rhywbeth i’w wneud gyda’r ffaith fod yr erthygl yn yr ail gyflwyniad ( yr un gyda hysbysebion a lluniau), yn goresgyn yr erthygl gyda’r lluniau a hysbysebion hynny mewn un cawdel o eiriau a lluniau annealladwy. Felly rydw i wedi mynd yn ôl a’i ail-ddarllen yn y fersiwn moel sy’n cyrraedd drwy’r ebost. A dydw’i ddim callach! Yn fy nghartref, rydw i’n byw drwy’r Gymraeg. Fyddai fy ngwraig na minnau byth yn ystyried defnyddio’r iaith fain heblaw wrth ddyfynnu rhyw eitem papur newydd neu ragen deledu. Ond ar… Read more »

Yn union

Thank you – this is something I’ve been grappling with (as someone who has moved to rural Wales) but not had the words for!