Daniel G. Williams: Why the political thinking of Raymond Williams remains so relevant

Daniel G. Williams with the first in a series to mark the 2021 centenary of Raymond Williams’ birth.

Raymond Williams begins his ‘Notes on Marxism in Britain since 1945’ (1976) like this:

‘The neo-Marxist Left which now dominates the Labour Party’, said a speaker at this year’s Conservative Party conference. Or it may have been ‘near-Marxist Left’, given the difficulty of ruling-class English with the consonant ‘r’.

As John Barnie notes in a recent moving memoir for the Raymond Williams Foundation, Williams – born and brought up in Pandy near Abergavenny – ‘spoke with a gentle Herefordshire bur of the kind you find in the border country when you near the Golden Valley’. To read Williams’s writings with an awareness of this background is to encounter, repeatedly, instances where an oppositional perspective – of class, nation and accent- is being deployed.

In recalling the gestation of his career-making volume Culture and Society (1958) – a dissection of the meaning of ‘culture’ in English thought since industrialisation – Williams noted that ‘my distance from Wales was at its most complete’. But even here, the ability to discuss English intellectual culture as an object of analysis, as opposed to an unarticulated position from which to speak, required an outsider’s perspective.

This is presumably what Williams meant when he noted that, despite that distance ‘my Welsh experience was nevertheless operating on the strategy of the book’. Indeed, Williams’s position as a Welshman writing about English culture in a British state was somewhat like that of two other colonial outsiders discussed in his book for their resonant accounts of English culture; T.S. Eliot and George Orwell.

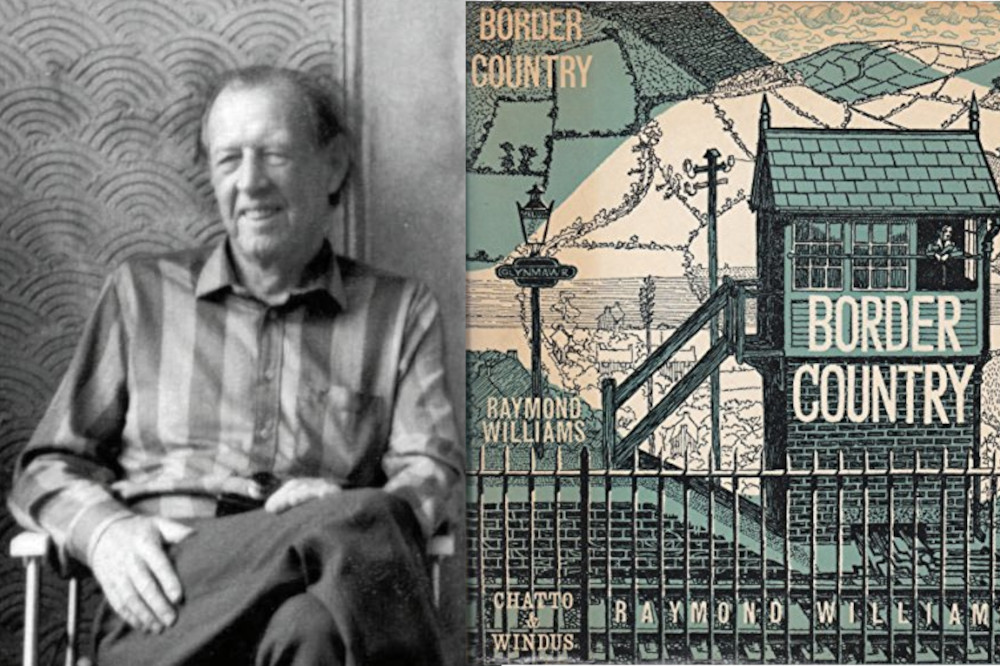

That unconscious underpinning became overtly conscious as Williams’s work developed; informing the action of all seven of his novels from Border Country (1960) to the two posthumous volumes of The People of the Black Mountains (1989), and increasingly and insistently evoked in the introductions to his seminal works of literary and cultural criticism.

‘Shift’

Readers of Nation.Cymru might be particularly interested in the shift in political allegiances that occurred in the 1960s. Having been a Communist on going to Cambridge in 1939, Williams was unaffiliated after the war – in which he was captain of an anti-tank regiment in the Normandy campaign – though he broadly shared his father’s allegiance to the Labour party and campaigned for Harold Wilson in 1964.

The May Day Manifesto – developed in collaboration with historian E. P Thompson and critic Stuart Hall, distributed for discussion and commentary by socialist groups in 1967 with a fully revised version appearing as a Penguin paperback under Williams’s editorship in 1968 – reflected a profound disillusionment with the Labour government and aimed to unite a range of influential socialist voices around a coherent programme that would revitalise the Left within the party.

The manifesto was ignored (even by the Labour Left’s journal Tribune) and by 1969 Williams had joined Plaid Cymru. In the essays collected in Who Speak for Wales? (2003 – with a new Centenary edition released this year), Williams located the language activism of Cymdeithas yr Iaith and the ‘radical minority nationalism’ of Plaid Cymru within the broader coalition of movements – Civil Rights in the USA and Ulster, feminism and the nascent ecology movement – that constituted the New Left.

Informed by this new perspective, The Country and the City (1973) is an impassioned critique of dominant, metropolitan, ways of seeing the periphery, and mounts a case for anti-colonial struggle and peasant revolt. Those struggles are, as always for Williams, cultural as much as political or economic, and in this volume the ‘selective tradition’ of the English literary canon is brought up against not only Welsh and Irish texts but also African and Indian sources of inquiry.

Raymond Williams’ intellectual career can be seen to cover a decisive period in the history of the Left: beginning as a key contributor to a New Left seeking a third way beyond Stalinism and social democracy in the 1950s, moving from the anti-war and student movements of the 1960s to Eurocommunism and the new social movements of the 1970s and 80s which saw his greater interest in Welsh intellectual and political debates coinciding with an increasing engagement with European Marxism.

Throughout, Williams responded to the intellectual and political changes around him while remaining committed to a politics of class, an assumption of equality with ordinary people and a resistance to the tendency – manifest in the writings of the Frankfurt School, the New York Intellectuals and of key strains of European Marxism alike – of treating the working class as passive victims, irredeemably corrupted by TV and mass consumption.

In an era of dogmatic divisions, Raymond Williams’s instincts were towards conciliation and bridge-building, whether between the humanist and theoretical Left in the 1960s, or the nationalist and socialist strains of Welsh thought in the 1980s. This tendency, which we desperately need to learn from today, may account for the way in which he is continually turned to as a resource of hope for the Left, particularly in periods of retreat. Writing in 1963 he foresaw our current predicament, and identified the need for an alternative:

“It will be a bloody tragedy if we betray Europe by being pseudo-Europeans, or by being so ‘English’ that we find ourselves in the wrong century facing the wrong problems. Still, to have two parties, locked in amplified combat and both wrong, is what we’ve had to get used to for years. It’s time for a change, don’t you think?”

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Good piece, thanks Prof, we desperately need to apply some intellectual rigour to our current predicament.

Diolch, Daniel.