How Wales and Welsh mythology inspired legends of ’70s rock

Leon Barton

The 1970s were – amongst other things – the decade of rock ‘n’ roll decadence. An era of Rock Gods (and the occasional Goddess) swaggering their way across the stadiums of the world in a way that simply hadn’t been done before (The Beatles played their final gig in 1966, Elvis Presley was put to work making forgettable movies rather than touring. Indeed, he never played a single concert outside of North America)

The Stones, The Who, Pink Floyd, Wings, The Eagles, Led Zeppelin, Fleetwood Mac and many more… ‘Hitlers rallies were no more than rehearsals for what was to come in the seventies’ Yardbirds manager Simon Napier-Bell once said.

But the top Welsh rock bands of the era never made it to that level.

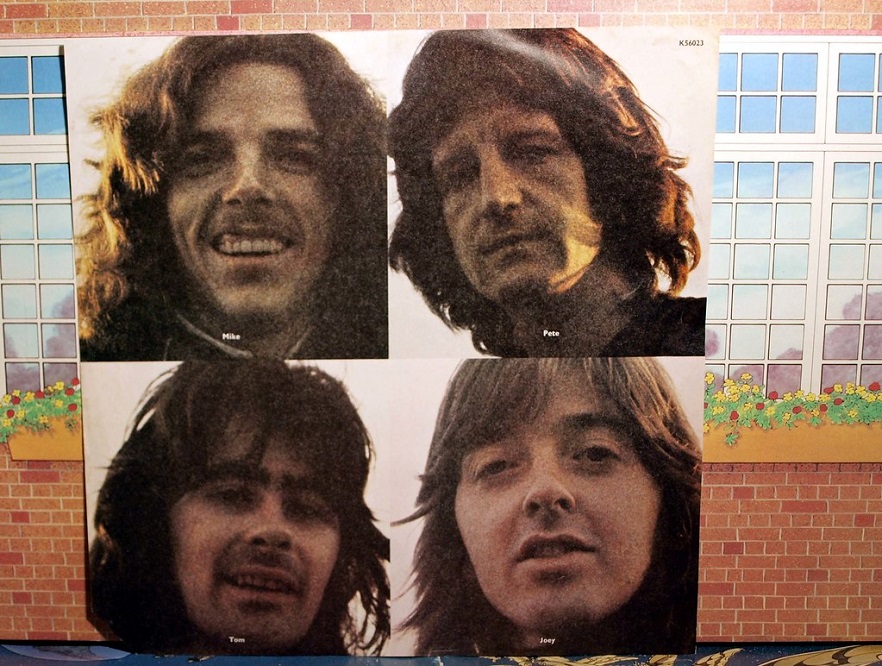

At one point Badfinger looked the most likely. In signing to The Beatles’ Apple label they seemed set to take their baton into the next decade. But, beset by wrangles with management and a lack of money, life became so unbearable that frontmen and principle songwriters Pete Ham and Tom Evans both sadly took their lives (in 1975 and 1983 respectively)

The Paul McCartney penned ‘Come and get it’ was their first single and it almost seemed to throw down the gauntlet to his young protegees; ‘if you want it, here it is, come and get it’, went the refrain. The band really hit their stride when they started recording their own material, with tracks like ‘No matter what’ and ‘Day after day’ arguably inventing a new sub-genre; power pop. The Ham/Evans-penned power ballad ‘Without you’ did become a huge worldwide hit in 1972 but that was for Harry Nillson. The insidious mechanisms of the music industry – particularly the immoral deeds of manager Stan Polley – then worked to ensure that Ham and Evans were not as financially remunerated for writing such a monster smash as they should have been.

Tragically, the baton was to remain ungrasped.

Budgie

Cardiff’s Budgie were a massive influence on the stadium-filling metal bands of the 1980s and beyond – the likes of Metallica and Iron Maiden – but only four of their eleven studio album charted in the UK, with the 1974’s ‘In for the kill’ the highest placed at number 29. The sleevenotes for ‘The Best of Budgie’ somewhat tellingly describe their cover of ‘I aint no mountain’ as ‘almost a hit single’

That song was written by fellow Cardiffian Andy Fairweather Low. As part of Amen Corner Low had enjoyed a massive hit in 1969 with ‘(If paradise is) half as nice’ but the band weren’t able to make the transition from ‘pop’ to ‘rock’ that was a requirement to fill stadiums in the seventies. Low instead became a leading right hand man to the likes of The Who, Eric Clapton and Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters, themselves of course part of the new ‘Rock’ elite.

Dave Edmunds also had a massive hit single at the turn of the decade with a cover of 1950s rhythm and blues song ‘I hear you knocking’. But he seemed happier in the studio than on stage, becoming a virtual ever-present at Rockfield, the famed recording facility just around the corner from his Monmouthshire home.

And then there was Man. The Merthyr band were continually tipped for the top, but even music journalist Michael Heatley – who ran the Man fans newsletter for twenty years – conceded that they only reached ‘the upper second division of British rock’

No Welsh act of the era achieved promotion to the Premier league.

Whilst Wales may not have produced a single seventies rock behemoth, the influence of Wales and Welsh mythology certainly played a role in shaping the sounds which filled the stadiums. Including the biggest beast of them all.

There’s a feeling I get when I look to the west

It’s 1970, and having marauded (there’s really no other word) their way around Europe and North America for the best part of the previous two years, playing bigger and bigger venues, guitarist Jimmy Page and frontman Robert Plant of Led Zeppelin decamped to a tiny cottage with no electricity or running water, on a hilltop overlooking the Dyfi valley; Bron-Yr-Aur (‘hillside of gold’).

‘From an early age my mum and dad took me to west Wales’ Plant told AC/DC frontman Brian Johnson for the latters Sky Arts show ‘A Life on the Road’. ‘I was really interested in the different culture between the original tribes and those coming in from Europe. They just pushed all the Celts and original Celtic tribes back into these hills… when I was at school I was intrigued by the difference between the two cultures, the history, the whole idea of mythology, stuff like that. Coming from the Black Country, this – compared to the industrial Midlands – was such a relief’

Later on, for Plant, Bron-Yr-Aur represented a ‘retreat from the madness of touring in the Led Zeppelin days; it was great because it was so far away from the chaos, the complete turmoil…coming to Wales gave us the kind of foundations for Led Zeppelin III, which was much more pastoral and acoustic based’.

When Plant describes touring with Led Zeppelin as ‘madness’ he’s not exaggerating. ‘It was a 24 hour a day assault on all the senses. I’m not kidding, I rarely slept’ is how photographer Neal Preston recalls life on the road with the band. ‘They lived like the Romans without the lions’ is rock journalist Mick Wall’s description. ‘Consuming drugs by the bagful, their minds scrambled in a morass of music, violence, sex and fan worship… they went beserk’ thinks Simon Napier-Bell.

Stunning

Bron-Yr-Aur provided a significant contrast. ‘Look at this place, it’s stunning…. Stairway to heaven’ gushes Brian Johnson in describing the tranquility of the Welsh countryside, whilst referencing the song that would become the centrepiece of the album which followed III, the all conquering IV.

That release also featured ‘Battle of Evermore’, perhaps the apogee of Page and Plant’s interest in the traditional folk music of the British Isles. A duet with ex-Fairport Convention singer Sandy Denny, it drips with mythological and supernatural imagery. ‘It suffered from naivete and tweeness’ admits Plant, ‘but I was only 23 and it makes up for that in the cohesion of the voices and the playing’. It was one of a number of Led Zeppelin lyrics to bear the influence of Lord of the Rings and JRR Tolkein. Tolkein himself of course was also a committed Cymrophile, famously once saying ‘Welsh is of this soil, this island, the senior language of the men of Britain and Welsh is beautiful’.

More directly, the author posited that ‘The Lord of the Rings’ was his own translation of the mythical ‘Red Book of Westmarch’ and his inspiration for this repository of lore was the real Red Book of Hergest, the early 15th century compilation of Welsh history and poetry that contains the manuscript of the Mabinogion. Bound in red leather and housed at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, the manuscript was well known to Tolkein.

Page and Plant loved their time in the Welsh countryside so much that the name of the cottage at which they resided was to feature in two songs. ‘Bron-Yr-Aur’ is a gentle instrumental that appeared on 1975’s ‘Physical Graffiti’. ‘Bron Y Aur Stomp’ (the misspelling was accidental) is an acoustic hoedown, with Plant eulogising his ‘blue-eyed Merle… the finest dog I ever knew’, and was one of III’s most straightforward moments.

But more generally, the likes of ‘Friends’ and ‘That’s the way’ are far more reflective than the material on the first two albums. Those records sound fantastic but ‘Dazed and confused’ is basically a rip off of Jake Holmes 1967 song of the same name, II’s ‘Whole Lotta love’ lifts the vocals from Muddy Waters’ ‘You need love’, and so on. Of ‘Friends’ Plant told The Guardian’s Jude Rogers ‘there’s something really splendid and otherworldly about trying to touch bigger ideas… to go past the idiom of singing about bars and chicks and all that crap, which unfortunately is the lingua franca of popular song. There are other dynamics of life, and we started to recognise that here’.

Downtime

It could be argued that the downtime at Bron-Yr-Aur was what turned Page and Plant into proper songwriters.

Now in his seventies Plant has retained his love of all things Wales, with 2014’s ‘Embrace Another Fall’ even featuring a verse in Welsh, courtesy of Fernhill’s Julie Murphy. That section of the song is based on a folk tale about a nightingale accidently killed in battle, whose body is brought back on the instruction of Owain Glyndŵr. Plant is an active member of the Glyndŵr society, something he describes as ‘basically me and a load of retired teachers in a coach looking for his grave… “Let’s pull into this layby, boys, it’s time for sandwiches!”

Which sounds utterly surreal but it’s this kind of activity that the septuagenarian Plant sees as much healthier than embracing the absurdity of the Rock God status bestowed upon him in America; ‘there’s no respite there… it’s so important to unhitch that ridiculousness’.

Wales quite obviously still helps him unhitch as much now as it did when he was a child.

Welsh witch music

It’s 1974 and Fleetwood Mac are floundering. Four years on from the departure of founder, frontman and guitar genius Peter Green the one time British blues superstars of the late sixties were lacking direction, having gone through a series of replacements for Green. The latest – Bob Welch – had just departed. Then drummer and defacto bandleader Mick Fleetwood thought he’d found a lifeline in the shape of Californian singer songwriter and guitarist Lindsey Buckingham. Following Fleetwood’s approach, Buckingham agreed to join the band on one condition; his girlfriend and musical partner Stevie Nicks could join too. A desperate Fleetwood acquiesced.

With her father’s job as president of Greyhound busses meaning the family constantly moved around the USA, Nicks spent her adolescence obsessively playing records, and living in her ‘own little musical world’.

Nicks’ ability to conjure worlds in songs was present in something she’d recently been working on, something she’ll soon take to introducing onstage as ‘a song about an old Welsh witch’.

‘I got the name out of a book that I read about two months before we joined Fleetwood Mac. And it was just about a lady who lived in Wales that had two personalities. One was called Branwen… which is a Welsh name also… her real name was Branwen… and this other personality that came in and took over was Rhiannon. I read the name and thought, ‘that’s really a beautiful name’…sat down; tap, tap, tap…about ten minutes later wrote the song’

That book was ‘Triad’ by American author Mary Bartlet Leader, a novel about a writer who becomes convinced she has been possessed by the spirit of her dead cousin.

Rhiannon was one of the most memorable moments on the eponymous 1975 record which was to turn the bands fortunes around, eventually becoming Fleetwood Mac’s first US number one album, fifty-eight weeks after first entering the chart.

Blitzed

But Rhiannon truly came alive onstage. ‘It’s a heavy-duty song to sing every night’ Nicks told Crawdaddy magazine in 1976. ‘It’s really a mind tripper. Everybody, including me, is just blitzed by the end of it. And I put out so much in that song that I’m nearly down. There’s something to that song that touches people. I don’t know what it is but I’m really glad it happened’.

That process of ‘putting out so much’ manifested in something that appeared close to an act of possession. Even talking about the song seemed to take Nicks into a different realm, as evidenced by an interview with Rolling Stone magazine in 1979; ‘This is Rhiannon, without a doubt. (The picture, of Nicks, does not look like her) Well, you see, it turns. It goes right into…(she pulls out another photograph, of herself on stage with Lindsey) This is the killer. And the pale shadow of Dragon Boy, always behind me, always behind me. (She is speaking almost to herself, in a hoarse whisper) You see, I just want to make you realize that when I get carried off, really carried off into Rhiannon, it doesn’t necessarily mean I’m not carried off into Fleetwood Mac. ‘Cause I’m just as carried off into them. Rhiannon has to wait. She just has to wait…’

Nicks told Mojo magazine in 2013: ‘It wasn’t until 1978 that I found out about The Mabinogion and that Branwen and Rhiannon are in there too, and that Rhiannon wasn’t a witch at all; she was a mythological queen. But my story was definitely written about a celestial being. I didn’t know who Rhiannon was, exactly, but I knew she was not of this world.’

In this way, by twisting the story, and taking it in another direction, Nicks was adding to the tradition. The tales which eventually made up the Mabinogion were told orally for centuries before anyone thought to commit them to writing. ‘They had thus no fixed and involuable form, but took shape and colour from a hundred minds, each with its human disposition to variance and mutability’ wrote Gwyn Jones and Thomas Jones in the introduction to their 1949 translation.

‘This legend of Rhiannon is about the song of the birds that take away pain and relieve suffering. That’s what music is to me’ Nicks confided, although music was not the only tool she used as pain relief. After all, we’re talking about a woman who once described cocaine as ‘a bit more-ish…like Sara Lee cheesecake’. But seemingly no substance could match the power of the spell cast by her fictional celestial heroine. As Mick Fleetwood recalled, ‘her Rhiannon in those days was like an exorcism’.

Nicks obviously relates to Rhiannon, so much so that she named her publishing company ‘Welsh witch music’. She even put in a tongue-in-cheek appearance as a witch in the ‘American Horror Story’ series ‘Coven’ in 2013. This, mercifully, showed an ability to laugh at the once-rampant rumours that she was an actual practitioner of witchcraft, rumours that had once caused a great deal of anguish and forced a change of wardrobe. ‘I just wear black because it makes me look thinner, you idiots!’ But, for a few years at least, Nicks swapped black for apricot, at least until the noise died down.

So, even if Wales failed to produce a single Rock God or Goddess for the duration of the seventies, a strong Welsh influence – whether through passion or theatrical possession – was, thanks to Plant and Nicks, to reach the stadiums anyway.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

What an excellent article, nice to know Mr Plant still remembers his time in Wales, and the background story about Rhiannon is very interesting.

Robert lived in Wales for a few years while recording solo albums at Rockfield.

He STILL lives in Eglwys Fach, Dyfi Valley

The story of how it all ended for Badfinger, has to be the saddest in rock history, young talented musician’s taken for everything, including their lives.

I feel sorry for the young people of today for missing out on the best times of the 60s /70s that they will never see the young people of today have missed the best times and they would be a lot happier people than they are today

A very enjoyable, fascinating read – can we add other moments such as Ballad of the Beacon by Wishbone Ash? A celebration of Eryri by a colossal band!

Knew some of it, but not all. Very good, diolch. Is thr Bron Yr Aur music shop still in Bangor?

Stevie Nicks ‘Rhiannon’ 1975 is what broke the Mabinogi out of its Welsh home into an international following. The original work had been translated into English since Pughe in the 18thC but it took rock to blitz the world with it. Most who enjoyed ‘Rhiannon’ knew no more than Stevie about the original Welsh stories. But gradually this, together with Evangeline Walton’s 70s fantasy novels, and the Goddess movement, built more awareness.// ………………………… However it is still assumed these are myths, fables, when they are also one of the pioneering literatures of the world. This was the first time stories… Read more »