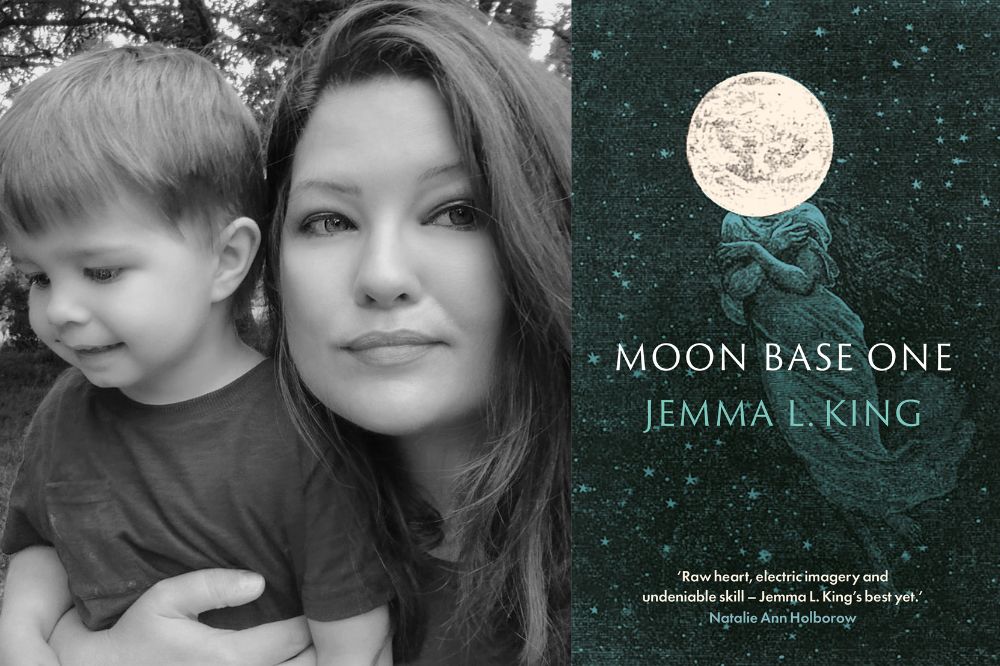

Interview: Jemma L. King on her poetry collection ‘Moon Base One’

Imogen Davies

Moon Base One is an extraordinary collection of poetry born from the most profound of human experiences – love, loss, and the fight for life itself. When poet Jemma L. King learned that her unborn son faced life-threatening conditions, her world unravelled. In his first fragile months, she turned to poetry to make sense of the impossible, asking: what happens before we begin, and what happens when we meet our most significant endings?

Spanning centuries and continents, this breathtaking collection moves through time and space – from the icefields of Antarctica to the Salem Witch Trials, from ancient Greek myths to the neon-drenched visions of Warhol and McQueen. King’s verse travels to the stars and back, interrogating the boundaries of existence, the fragility of life, and the fierce power of motherhood.

With exquisite lyricism and unflinching insight, Moon Base One is a meditation on survival, rebirth, and the ever-unfolding mystery of what it means to be alive. A cosmic, deeply personal journey that pulses with wonder, it reminds us that even in our darkest moments, we remain part of something vast, luminous, and filled with possibility.

What inspired you to write ‘Moon Base One’?

Well, the starting point, really, was the run-up to my son’s birth. About a month before he was due, we discovered that he had some life-threatening health problems, and that he’d need to be taken straight to Birmingham Children’s Hospital for life-saving surgery as soon as he was born.

Because of those circumstances, I couldn’t hold him or cuddle him because he was in an incubator and hooked up to so many machines, and in fact, for the week immediately after his birth, I was in an entirely different city to him because I was recovering from the C Section. So it was odd, like I’d had a baby, but there was no baby.

I busied my hands and stilled my mind by connecting to stories of extremity, and of inspiring people. I largely wrote about people who lived consummate lives, people like Frida Kahlo, Apsley Cherry-Garrard of the Scott Expedition, Joan of Arc, Andy Warhol, Alexander McQueen, the Salem Witches, Percy Byshhe Shelley, etc. All of that pulled me out of the confusing scenario I found myself in.

In addition to those ‘other people’ poems, I had a thread running throughout where I tried to make sense of the situation itself. One of the metaphors that I kept returning to was that my son was on a different planet or satellite to me – I used space and mythology a lot to explain my emotions to myself. Hence the title of the book, ‘Moon Base One’.

What was the creative process behind writing ‘Moon Base One’?

Basically, I sat next to Sol’s incubator in the hospital and wrote like hell!

I’m generally quite a spontaneous writer – I’ll just write where the mood takes me. And for the poems in the book that are about my son, that was still the case. I’d put pen to paper and whatever happened, happened. Sometimes, he was an astronaut on the moon, sometimes he was the planet Mars, losing its atmosphere. Sometimes, he was a whale calf floating quietly through the sea, sometimes, I was Andromeda, chained to the rocks about to have my unborn child stolen from me. And sometimes, the poetry from these sequences was just plain, stark.

But then the bulk of the book was a very deliberate process, given that it was to serve as a form of catharsis. I wrote a big list of fascinating historical figures, or scenarios that have interested me. I tried to get up close to these people and events in my mind, to try to understand what the point of everything was. It was a big question and I make no claims that I’ve been successful, but really, every poem about other people was a conversation with them, mentally, to glean their wisdom. It’s all fiction, obviously, but it felt like the best way to try to make sense of the world. And in that period, it all helped.

Given that ‘Moon Base One’ is your third collection, how and in what ways has your writing changed and developed since penning your first, ‘The Shape of a Forest’, in 2013, and your second, ‘The Undressed’, in 2014?

That’s a really good question and one I’ve been thinking about quite a lot.

I don’t think I’ve ever been a ‘confessional’ poet by any measure, I’m too interested in other people and other lives. Hence my first collection being about Amelia Earhart, Genghis Khan etc. And my second being all about naked Victorian women!

For me, this book is my most personal yet. This is as close as I get to confessional. I still balance it up by keeping a foot in the lived experiences of others, but I also just wrote about what I was going through. In some ways, that was quite hard – whenever I imagined an audience reading the book, that gave me pause for thought. Have I earned the right to just talk about myself?

But that’s what I’ve done so this feels like a markedly different project to The Shape of a Forest or The Undressed.

‘The Valley’ and ‘Blodeuwedd’ are two poems that capture a specific element of Welsh culture, ‘The Valley’ commemorates the Elan Valley which was flooded in 1896 to create a dam that would supply water for Birmingham, while ‘Blodeuwedd’ is a reference to the female character from the last branch of the Mabinogion. How has Welsh cultural history as well as your own relationship to Wales impacted and shaped your writing?

I’m half-Welsh and half-English, and being that faultline has always been a strange position. I’ve lived in Wales for longer than I’ve lived in England, but when I’ve achieved things relating to Wales (such as being shortlisted for The Wales Book of the Year prize etc.) I have had Welsh family members (!) complain that I’m ‘not even Welsh’. I get it on both sides, I’m not English enough, not Welsh enough. Perma-interloper!

So I’ve always had that back and forth, understanding and appreciating both sides of my history, I suppose to understand the fractals of my identity as perceived by others.

There’s no tension in it for me though, I love exploring Welsh culture and I think I’ve read The Mabinogion so many times now, that the mythology is a part of the internal tapestry.

So when writing about leaving an abusive man, Blodeuwedd is the reference I naturally turn to. And in The Valley, I suppose I’m still thinking about that intersection between England and Wales. It’s always been a difficult relationship, and that story typifies the exploitation and disrespect that has made it uneasy – to this day!

Your collection spotlights various women from throughout history, from literary and mythical figures such as Blodeuwedd, to Elizabeth Howe, accused in the Salem witch trials, and reference to Evelyn McHale, whose suicide inspired Andy Warhol’s artwork, Suicide: Fallen Body (1962), which is depicted in your poem of the same name. What is it that interests you about women’s lives? And why do you think they are important to commemorate through poetry?

Clearly, women have had a rough run through history. We either get ignored, or we are window dressing, or we are chained to rocks to be sacrificed to sea monsters!

I’ve always been interested in returning voices to women whose stories we think we know, but don’t.

Evelyn McHale is a good example. She threw herself from the top of the Empire State Building, and a passing photographer took a shot of her dead body lying on top of a Cadillac at the foot of the skyscraper. Her last wish, in her suicide note, was that her family shouldn’t see her body, and yet that image of her death (which became known as ‘The most beautiful suicide’) was turned into an artwork by Warhol, and is now one of the most enduring images of the twentieth century. It even ended up on the cover of Time magazine. Her wishes, even in death, were not important, because she was deemed attractive.

So that’s why it’s important. Ditto with the Salem witches. A narrative was ascribed to them that just isn’t true. They weren’t in league with the devil – it was simply that the harvests of Salem were blighted with ergot, a hallucinogen, or at least, that’s the latest theory about what happened there. But they swung for it. So I wanted to return power to them.

As well as Andy Warhol’s work, you reference other art forms such as the fashion of Alexander McQueen’s ‘Joan’ Autumn/Winter collection from 1998 and Eduardo Paulozzi ‘Vulcan’ sculpture. Do you think ‘Moon Base One’ could be expressed in any other form apart from poetry or is poetry the best form for the collection?

I’m synaesthetic so for me, the written word contains colours, tastes, shapes etc. My brain is probably quite spicy but I haven’t been diagnosed with anything because I’ve never bothered pursuing that.

But given that everything has texture and movement to me, I do tend to imagine all of my poems visually. I do toy with the idea of creating sort-of-music videos for my poems. Spoken word but overlaid with images. Basically, there’s not enough time in the day. But eventually, I might try that.

I am conscious, when I’m writing, that I’m trying to really get across what’s going through my head, which is why I crunch through so many images per poem. It might be fun to do something with image and music in the future.

The collection reads as a very personal documentation of time passing during pregnancy and motherhood, beginning with the poem ‘3-month scan’, followed by poems such as ‘Today they scalp you out’ dated, 14.02.22, 1pm, ‘Telford Women and Children’s Unit, 1am’ and ‘Arrival at Birmingham Children’s Hospital’. What role did writing and poetry play for you during this time?

It was serious self-therapy.

My life is permanently busy. I always have about 7000 things on the go at the same time, and when you have a baby, you prepare to stop. The schedule was entirely cleared, for the first time in adult life, to focus on the baby.

And then there was no baby to look after. And also, I’d had to relocate to a city that was pretty alien to me, for an indeterminate length of time. Everything was frightening and intimidating. I was simultaneously forced to live in the moment (too scary to look forwards) but I also had nothing to do in the moment, except stare into space.

So the book gave me a practical way to deal with everything, and it took my mind off all of the ‘what ifs’ that kept running on a loop, through my mind.

What do you hope readers will take away from this collection?

I hope they read hope into it!

I’m ever an optimist and most people who know me would describe me as having a sunny, glass-half-full personality. So this collection, despite the origins of it, isn’t a headlong descent into defeatism.

It’s the opposite of that – it’s about roaring in the face of adversity.

It’s about sitting with those difficult moments and facing right up to them, but essentially, being grateful for everything that adds up to the sum of our life and our inheritance as human beings.

Even as we face all of the manifold challenges that we all do, our species is still aiming to take our place amongst the stars, and that’s the overriding thing about humanity to me. We never lose hope.

‘Moon Base One’ is available now, published by Parthian Books.

Jemma L. King won the Terry Hetherington Young Welsh Writer of the Year Award and was shortlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize, the Wales Book of the Year Prize and the Sundress Prize for her haunting debut poetry collection, The Shape of a Forest. Her second collection, The Undressed, was inspired by a cache of antique nude photographs of women, returning voices to those previously lost to history. The first prize winner of the 2024 International Cambrian Mountains poetry competition, Jemma’s latest work has been published by magazines including Acumen, Littoral, and Seaside Gothic. Moon Base One is her third collection. Jemma lives with her husband, son and dog in the Welsh countryside.

Imogen Davies is a writer and creative from Aberystwyth, currently undertaking a masters in modernist literature at the University of Edinburgh. Named as one of sixty New Welsh Poets ‘to watch’ by Poetry Wales, her first collection, DISTANCES, appeared in 2024.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.