Letter from Rio de Janeiro

A Welsh observer in Rio

On the 1st of January 2018, I was in Brazil with my husband’s family when Bolsonaro was sworn in as President. My mother and father-in-law threw a party, with the television blaring throughout, so that everyone could watch as Bolsonaro´s motorcade drove through Brasilia, and cheered as he ascended the stage to receive the Presidential Sash.

After a long four years, we finally manage to visit his family again. Only on this New Year ’s Day, just over half of Brazilians are celebrating a very different president. It’s one big party all across the country – concerts, speeches, excitement – but not for us. My in-laws spend the day doing their best to pretend it isn’t happening.

“I want an earthquake to swallow the Presidential Palace whole,” says my mother-in-law on our second day in Rio. Unlike what is reported to us in the Guardian, she is convinced Brazil is now on a downward trajectory. The economy will be devastated, hyperinflation will return, and bandidos (criminals) will be released en-masse from prison.

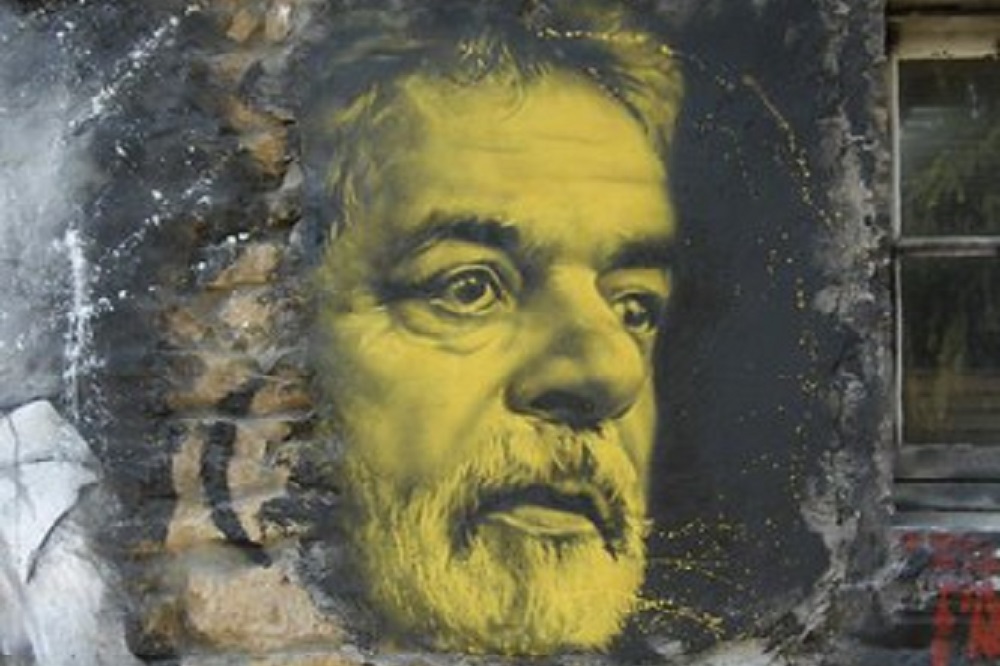

It is a strange experience, sitting with my progressive husband amongst his right-wing family, eating and drinking and saying absolutely nothing at all. Because there is nothing that my husband could say that could possibly convince them that Lula is not the devil incarnate.

We feel like spies, daring to exchange a glance, hoping that no one will ask us for our opinion. It also feels very familiar: another absolute political divide. Like a border wall that has grown bigger, taller, stronger – with no gateway or ladder. It´s Brexit Britain and Trump America, only I’ve never been so outnumbered.

“The army is a watermelon. Green on the outside, red on the inside,” says a neighbour. He refers to the Bolsonaristas disappointment in the army. They seemed so pro-Bolsonaro and now that he has been voted out (in an “unfair” election), they do nothing to bring about the coup he promised.

Fear

For weeks, Bolsonaristas protested outside the Army Headquarters in Brasilia. My mother-in-law also protested in the streets of Rio directly after the election results.

Even now, after spending two weeks with her, I can’t say that I have come any closer to understanding why anyone would campaign for a military dictatorship. Fortunately, my Portuguese is not sufficient to enter into any arguments.

But her fear is real – fear of economic and social collapse, fear of corruption (after all, Lula was involved in the biggest corruption scandal in Latin American history), fear she and her family might lose it all.

The fear is not helped by the conspiracy theories and fake social media news she is quick to believe and share, at one point claiming that a pro-Lula politician promised to introduce a 100% inheritance tax, due to a heavily edited video that went viral in Bolsonarista groups.

At another point suggesting that Lula’s “violent” followers were setting Bolsonaro-supporting businesses alight across the country.

Rejoicing

On the first day of Lula’s presidency, we sit around the same table as four years ago. But this time, nobody talks about politics. I drink my cup of cold agua de coco, eat the delicious brigadeiros and am quietly – silently – rejoicing that brilliant environmentalist Marina Silva will now be the Minister of the Environment and the Amazonian inferno might just end.

I am quietly rejoicing that LGBTQ+ community will no longer be a target of a prejudiced government, and that Lula will finally create real ties with other countries – and resume Brazil’s role as a powerful diplomatic force…

But I am also sorry that political conflict has caused so much pain, has become so extreme, so dangerous and violent. Outside, at the end of the evening, the fumacê rumbles up the road, spraying insecticide. Soon, the floor is covered in dead mosquitoes.

Later in the week, we meet up with some of my husband’s university friends. I mention how odd it is that my in-laws assume I agree with them, even though I have never said anything to suggest that I do. “Of course they think you agree with them. You’re white,” says our friend.

We are in a park in Ipanema, letting my three-year-old run amok in the playground. Ipanema is a wealthy, bougie part of the city. There aren’t many playgrounds, and so the one we find is extremely busy. I notice that there are many more women of colour here than on the streets of Ipanema. In fact, almost all the women are.

I am told they aren’t mums – at least, not to the white children who they are caring for – but babás – babysitters looking after the young children of the Rio middle-classes.

The racial divide strikes me more than once. In a gated condominium we visit, all the workers are people of colour – the gardeners, cleaners, concierges.

Racial divide

The majority of the residents are white. I had known this before on my previous visit, but after Bolsonaro and everything that has happened in the last few years, the racial divide feels more pronounced somehow, more terrifying – because it is a vision of a Bolsonaro Brazil, where marginalised communities are further othered and oppressed.

It may also be because I have had a child and am more aware than ever of different types of work – visible and invisible – or perhaps because, on my first visit, I saw Brazil, and my husband’s language and culture, through a haze of love and excitement. Now we have been married for years, I see it as a country like any other country. Beautiful but with its own problems.

As I am writing this, Bolsonaro has fled the country for the United States. He fled the election night too. While his supporters stayed up, waiting for his speech denouncing the elections, he slunk off to bed to sulk. This doesn’t feel much different.

He is scared of being imprisoned – just like Lula was – and has made efforts to get Italian residencies for him and his family. But for my in-laws, Bolsonaro is gathering his strength for a Second Coming, waiting for his opportunity to realise his dream of the military coup he and his supporters desire.

Although I am silently celebrating, wishing I could join in the “Lulapalooza” in Brasilia, I am also painfully aware of the many millions of people in Brazil who, like my in-laws, are not watching the television. I can sense the tension in the room, the terror and uncertainty of what’s to come.

The 49% of those who voted for him are so very angry and disappointed – and this anger, I fear, won’t go away.

You can find the entire series of ‘Letters from’ by following the links on this map

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

An extremely prescient piece of writing given the events in Brazil yesterday. Through the prism of one family the writer illuminates the stark divisions in Brazil’s society. This article shows great insight and humanity. Diolch.