Llyn Fawr: a breath-taking underwater discovery

Continuing our series written by John Geraint, author of ‘The Great Welsh Auntie Novel’, and one of Wales’s most experienced documentary-makers. ‘John On The Rhondda’ is based on John Geraint’s popular Rhondda Radio talks and podcasts.

John Geraint

I’m going to start this article with one of the most unsurprising, commonplace statements you can possibly think of. Boring, you might well call it. But stay with me. Because it’s led me back to something truly extraordinary, one of the greatest finds ever made within reach of the Rhondda.

A friend of mine posted a photo of herself on Facebook the other day.

‘So what?’ you’re saying. Fair enough. I can’t even claim it was a particularly good shot. To be honest, you needed some help just to spot her in the picture. “That’s me in the red jacket,” she felt obliged to point out.

She was proud of the photograph all the same. It showed her, you see, conquering one of her phobias. She was speeding at 70-miles-an-hour hundreds of feet above the Llyn Fawr reservoir on the Rhigos, thanks to Zip World Tower. The attraction is the fastest seated zip line in the world, according to the owners.

My friend did enjoy the experience, despite her anxieties, or so she claimed. Rather her than me though. I’m not an adrenalin junkie, not a thrill-seeker – well, not of that kind anyway.

Though that place – Llyn Fawr on the Rhigos – has given up a secret that really does take my breath away. And that’s what I’m coming to.

Panorama

Now, you know the place I’m talking about, don’t you? Head up past Treorchy and into Treherbert. Then, instead of bearing left for Tynewydd, carry straight on, up the Rhigos mountain road – providing, of course, it hasn’t been shut by snow, ice, rockfall or overly zealous council workmen.

Keep going, and eventually you’ll come to a viewing point with a fine panorama of the Brecon Beacons. Down below you is the old Tower Colliery – now the Zip World adventure hub. And to your left, nestled against Craig y Llyn, a reservoir.

Llyn Fawr – it just means ‘Big Lake’ and it’s called that, I suppose, because there’s a Llyn Fach, a ‘Little Lake’ just around the corner. My dad used to take me fishing at Llyn Fawr when I was a boy. The Upper Rhondda Angling Association still stocks it with what they call ‘hard fighting rainbow and blue trout’.

It was a natural lake before it was adapted for water supply. A few wild brown trout still swim there, or so I’m told.

The reservoir was created in 1909. At the time, the Rhondda was booming. Tens of thousands of people had moved in to work in the coalmines. This was ‘American Wales’, a modern industrial powerhouse, growing – as I’ve said – at a rate rivalled only by New York and Chicago.

Burgeoning population

The River Rhondda, it was becoming clear, didn’t hold enough water for the burgeoning population’s needs.

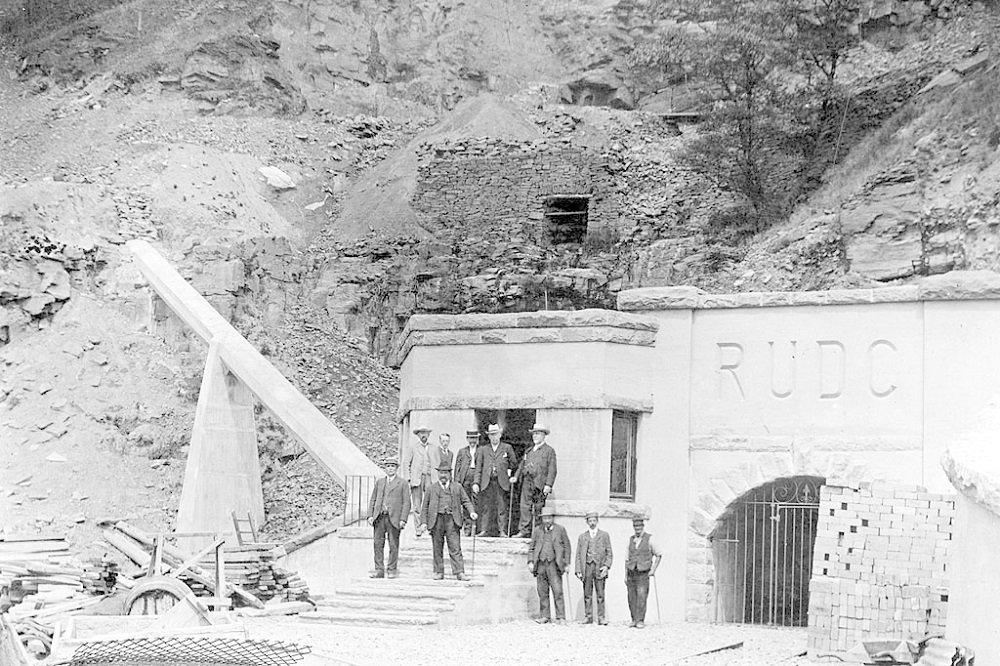

So the plan was to turn this natural lake the other side of the Rhigos into a reservoir, and then pump the water under Craig Y Llyn, through a tunnel a mile-and-a-quarter long under the mountain, to treatment works at Tynewydd. And that’s what happened.

The tunnel is still an important part of Welsh Water’s infrastructure supplying the Rhondda, though it’s well over a century old by now.

There’s a wonderful black-and-white photo which I’m guessing was taken not long before the work began – two men in suits and bowler hats with a horse and cart at the lake shore. I imagine them surveying, mapping out the necessary excavations.

Fantastic discovery

Eventually, in deepening the lake to form the reservoir, workmen – in dai caps rather than bowlers, I suppose – cleared vegetation that had lain undisturbed for more than two and a half thousand years.

And in doing that they made a fantastic discovery, one that still takes my breath away every time I think about it.

What they found, buried in waterlogged peat at the bottom of the lake, and so preserved in more-or-less mint condition, was a hoard of weapons and tools from the late Bronze Age. Twenty-one metal objects altogether, all now kept in the National Museum in Cardiff.

There were carpenters’ tools – chisels and gouges. Axe heads. Horse harnesses and bits – some of the finest decorative horse gear ever found in Britain.

And two spectacular bronze cauldrons made from hammered sheets of bronze painstakingly pinned together with bossed, bronze rivets. The cauldrons are so big you can’t get your arms around them.

Craftsmanship

But something else was found too, something else that really thrills me. After all, I come from a family of ‘notable mid-Rhondda craftsmen’ as the Rhondda Leader put it, in the obituary of my grandfather (have I boasted about that already?).

Tommy John was the blacksmith at the Naval Colliery in Penygraig at the time the Llyn Fawr discoveries were made. What was found amongst the ancient hoard of treasure was… an iron sword, probably made in eastern France.

From just one look at it, you can see that the blade is superbly grooved – the quality of the craftsmanship telling us that this isn’t just a blacksmith’s first-time effort with iron. This is a master at work, despite the fact that, 2700 – 2800 years ago, iron was something really new.

New and valuable – too valuable to have been left there in the lake without thought. From similar finds in bogs and rivers and lakes elsewhere, experts believe they’re offerings to a local god or goddess.

The reflective waters of the lake were seen as a boundary between two worlds – our world, and Annwn, the Celtic underworld, where the gods held sway. These precious artefacts were given up to the deities below, payments in return for the hope of good harvests, mild winters or fortune in battle.

But how did these gifts to the waters come to be here in Wales in the first place? Are they evidence of trade or war?

Fifty or sixty years ago, an archaeologist looking at the Llyn Fawr collection would probably have said that the foreign sword was carried here by an invader.

Today, most experts tend to think that it was trade, the exchange of valued goods, passing perhaps through many hands, from the far continent to the hills of north Glamorgan.

Native ironworking

Most intriguing of all to me, and I’m thinking of my grandfather again now, are two final objects amongst the discoveries: an L-shaped sickle and a short spear-head.

When the museum analysed the ore in them scientifically, they found that they were made not in France or anywhere on the continent, but here, near where they were found.

This is evidence that local smiths are beginning to transfer their skills in bronze to work in this even more useful new metal, iron.

We have to imagine a bronze smith somehow being introduced to or experimenting with the iron ores that you can find in the geology of the rocks of the Rhigos: experimenting with smelting, forging the iron and creating new metal objects in the old, familiar style of bronze work.

So these finds herald a whole new era in the human history of these islands: we’re in the dawn of native ironworking, not just in Wales but in the whole of the British Isles and Ireland, because these are the oldest native-made iron objects ever found here.

And believe it or not, ‘The Llyn Fawr Phase’ has become the official name of the beginning of the Iron Age in Britain, between 800 and 600 years Before Christ.

And it’s called that, all because Tommy John, my grandfather – and tens of thousands of other Rhondda people who may be your ancestors – needed drinking water.

All episodes of the ‘John On The Rhondda’ podcast are available here

John Geraint’s debut in fiction, ‘The Great Welsh Auntie Novel’, is available from all good bookshops, or directly from Cambria Books

You can find the rest of John’s writing on Nation.Cymru by following his link on this map

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Wild swimming in the high lakes of Ardudwy as a lad, the isolated peace of Llyn y Bi, the tragedy retold on the plaque beside Llyn Bodlyn, the story of the lakes of Cymru should be told over and over again…thanks for filling a gap…

A mention of Llyn Cerrig Bach on Ynys Mon and the Iron Age deposit discovered during the works extending the runway to accommodate the large American Flying Fortresses in 1942 is appropriate here I think…do look after them National Museum Cardiff…

Is this in the Rhondda?

Tommy John is part of my family tree. My grandfather was William Samuel John born 1862. He was a collier. I think Tommy was my mother’s brother. Some members of the family still have the bakestones he made over a hundred years ago.