Magnificent Mabinogi 7: Politics – mediaeval & modern

Dr Shân Morgain

Mabinogi politics, its power plays, are of two kinds. There is its historical context over the centuries, and politics within the tales themselves.

Political context affects how the stories are understood. Last week I outlined three main stages or schools of Mabinogi thought: Welsh, English and American.

Mediaeval origins

The Mabinogi was compiled c. 1100 from various local Welsh tales. The timing suggests a response of native pride against incoming, aggressive Norman bards.

Three surviving manuscripts appear at key political dates.

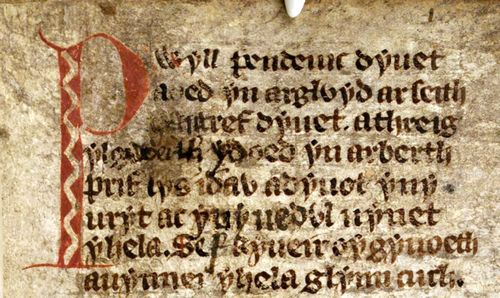

Peniarth 6 (c. 1250) scribed during a powerful period of native independence: Oes y Tywysogion/ Age of the Princes.

Llyfr Gwyn Rhydderch/ White Book (c. 1325–1400) was probably commissioned by uchelwr Rhydderch ab Ieuan Llwyd, a Ceredigion lord high in the English hierarchy, with consequently ambivalent loyalties.

English contempt for Wales entrenched. Parliament sneered ‘a nation of little reputation’ and the Welsh as ‘bare-footed idiots’ (*Brough).

Llyfr Coch Hergest/ Red Book was triumphantly created during renewed native independence: the Glyndŵr Rising (1385-1420s).

Its patron, southern uchelwr Hopcyn ap Tomas, reputedly met Glyndŵr as an adviser.

After the Glyndŵr Rising there was no native class of wealthy patrons to support further development.

Welsh tradition

Welsh scholars 18thC, 19thC used the tales as part of efforts to rebuild Welsh history and native pride. (See also last week). The 18thC London Welsh societies upgraded the Cymraeg from servant and peasant class talk to professional speech.

Diana Luft has researched 18thC scholars’ plans to publish the Mabinogi. It was asserted as among the first Romances of Europe, in a context of Welsh connections to European politics of revolution (e.g. Iolo Morgannwg).

William Owen Pughe published much of the First Branch (1795, 1799), an outline of the Second (1828), part of the Fourth (1833). He died 1835 with a full ‘Mabinogion’ ready to publish, including nine sketch illustrations for the First Branch.

Charlotte Guest, a wealthy English aristocrat, married into Wales, and published the first complete Mabinogi text (The Mabinogion series Parts 5 & 6, 1843, 1845).

In Mabinogi Studies’ accounts its ‘Welsh Renaissance’ is often overlooked in favour of Guest as a starting point.

Although English by background, Guest faithfully followed her Welsh mentors. I place her as end-point to this Renaissance, especially for her passion for the European Romances.

Anglocentric tradition

Guest and Pughe Mabinogi publications were bilingual texts, Middle Welsh and English. Guest published in Wales and London simultaneously. Even so, The Monthly Review applauded Guest for an important ‘acquisition to English literature’ (April 1843).

Only two Mabinogi excerpts had been English only text: Edward Jones (1802), and a Pughe reprint of his 1795 ‘Pwyll I’ in 1828. In 1852 Guest was widowed, departing 1855 back to England in a new English marriage.

Guest’s second edition Mabinogion (1877) was her English translation only, a drastically cut-down version. It cut the original Middle Welsh and the manuscript facsimiles. She intended it as a cheap, popular book, and it did reach a much wider, international audience.

This English-only version went from strength to strength and still flourishes today.

John Rhŷs the same year (1877), was appointed the first Professor of Celtic, Oxford University.

‘Celtic Mythology’ was part of a new movement of scholars studying the mythologies of different cultures.

These studies arose out of the worldwide conquests of the British Empire, turning a curious spyglass on the odd habits of its inferior peoples.

Matthew Arnold, an influential English poet and Government bureaucrat,, had dismissed the original Mabinogi storytellers (cyfarwyddiadau) as fools. With typical English arrogance he said they did not understand their own ancestral tradition (1866). He claimed the tales were broken remains of an ancient Celtic mythology.

The poet in Arnold fancied the idea of a lost Celtic mythology. Simultaneously as a Government schools inspector, he supported the English political programme to eradicate the living Welsh language. Mythology became a safe niche for Mabinogi enthusiasts.

Rhŷs, influenced by Arnold’s idea of ‘fragments of myth’, tried to reassemble an original ‘Celtic pantheon’ (1888).

It would provide a Welsh copy of the prestigious Greek and Roman pantheons. Rhŷs was educated in the Oxford Classics tradition which bred English snobbery.

Such a copycat Celtic ‘pantheon’ is unfounded. Inscriptions, texts by Greek/ Roman authors, imagery, legends, indicate Celtic societies did not have a pantheon. Deities were overwhelmingly local, with very few exceptions (notably Epona, Lugh).

Politically the Cymru has generally not been a centralised state.

Welsh inheritance law split estates between all children, and geography also prevented ‘unity’. Imposed English laws of primogeniture, and railways, somewhat reshaped this organic culture. Centralisation/ tyranny typically uses religious myths of unity, hierarchy, and a supreme god/dess.

Max Müller’s solar/ chthonic theory was another influence on Rhŷs. But he admitted Welsh myths did not fit.

He therefore reworked the Mabinogi tales and others, to fit the theory, changing characters and plot. ‘Mythological Reconstruction’ was born.

Pughe and the Welsh scholars were satirised and obscured by the Oxford Welsh Reform group (1890s) led by John Morris-Jones.

William John Gruffydd (WJG), a student of Rhŷs, greatly developed mythological reconstruction. His constructed ‘edifices’ were motivated by nationalist zeal to counter the Arnoldian insult. The product was a mishmash of sheer fantasy. (1912, 1953, 1955) which dominated Mabinogi thought in the 20thC.

The New Age and Goddess Spirituality of the late 20thC adopted Mabinogi material. Both construct their eclectic systems in an international, Anglocentric culture. (See my 4th article)

An Englishified culture of the Mabinogi has been vigorously developing since the late 19thC.

Often its makers and followers (Guest, Rhŷs, WJG, Celtic, Goddess, New Age) do not intend to deny the Welshness of the Mabinogi, but that is in effect what they do.

Politics within the tales

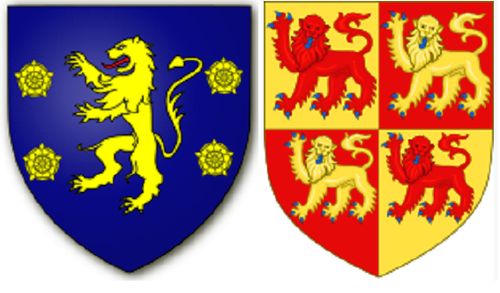

Mabinogi tales mirror mediaeval Welsh societies which produced them. The First and Third Branches feature Dyfed, the dominant power in the earlier mediaeval period. Both Mabinogi and history then move to Gwynedd dominance (Fourth Branch).

Having declared Welsh societies were historically decentralised it seems contradictory that the Mabinogi presents a unified Britain, with a hierarchy of king, princes and nobles. Its ‘Britain’ can suggests a message of restoration to the conquered, claiming the Cymru as the original, self-ruling Britons.

The Desolation of Dyfed, Third Branch, seems to resemble actual historical clearances of southern Dyfed and other Anglo-Norman features (12thC). Manawydan as New Man is a successful town trader, heralding the future.

The few ‘loan-words’ which Mabinogi language (Middle Welsh) adopted from Norman French, all relate to trade.

Another possible historical analogue is Pwyll’s stay in Annwfn, returning laden with honour.

Like him, Hywel Dda and other Welsh princes (10thC) went away to Wessex, forging peaceful alliance. Though said to be ‘homage’ there is no record of its payment.

Pwyll and Pryderi both hold Councils to negotiate difficult decisions. Advisors to princes are much respected, women or men. Advice is not always followed, the prince/ lord having the final word.

Pwyll, Pryderi, Rhiannon and Gwydion, practice the custom of cylch. A ruler moved around his/ her llysiau/ courts, collecting regional tax in kind, operating a decentralised economy. The resources were then redistributed by huge feasts organised by noblewomen.

Perhaps the most distinctive political pattern is sarhaed. The Welsh Laws did not employ violent punishments like the Normans/ English. A system of fines operated.

Everyone had their sarhaed value according to class and gender status. If you committed an offence you compensated that person (or their kin) their sarhaed. You paid in deer, cows, horses, pigs or your own bonded labour.

Arawn threatens Pwyll with sarhaed. Rhiannon’s choice to cheat Gwawl of his rightful compensation payment engines the Third Branch.

The Mabinogi is certainly no democracy. Sarhaed obviously allowed the wealthy to offend lower orders with impunity. Nonetheless, the Welsh Laws’ lack of violence took centuries for England to catch up.

………………………………………………………………………………………………

*Brough. 2 quotes given by Gideon Brough. (2017) The Rise and Fall of Owain Glyndŵr, p. 26.

All other scholars referenced can be found in my Mabinogi Bibliography; dates given above should be adequate to identify which work is meant.

Questions or comments are always welcome. You can contact me via LinkedIn or Academia.edu

The ‘Magnificent Mabinogi’ title was first used by the playwright director Manon Eames for her famous staging, Aberystwyth Arts 2008; used here with her permission.

‘Magnificent Mabinogi’ series. 1) Genius 2) Stories 3) Howlers 4) Canon & Construction 5) Places of power 6) Myth/ Literature? 7) Politics (above) NEXT 8) Everyday life

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

That’s a helpful history. I have Sioned Davies’ 2007 translation on my bookshelf and it has a useful introduction which covers similar territory.

Diolch Alan. Yes Sioned is nice, but very brief notes without anything like my detail or themes. Popular as a first step.

I would strongly recommend Bollard 2006 The Mabinogi, Legend and Landscape of Wales FREE PDF download. His Introduction and Afterword, plus useful little notes sitting conveniently right on the relevant page is all unbeatable for a more thorough read AND lavish photography by Antony Griffiths.

ps. Just checked Sioned Davies ‘Introduction’ to her Mabinogion (2007). She actually doesn’t give a history of the Mabinogi over the centuries as I do above. Not surprising for two reasons. One is her book covers the entire Mabinogion – that is the eleven prose tales, not just the Mabinogi. Such a broad coverage can’t give a history of each part in a short book. Secondly what Sioned does excellently both in her 2006 translation and her earlier 1989 (Cymraeg) 1993 (English) versions, is in depth research on the language and style of the tales. She and her mentor Brynley… Read more »