Why Newport is the true cultural and linguistic capital of Wales

Stuart Stanton

It may seem somewhat presumptuous to champion a claim that this recent city has the historic right to declare itself the true capital of Wales.

It has no obvious history earlier than the Norman Conquest and it was for over 400 years – until 1974 – legally a part of England.

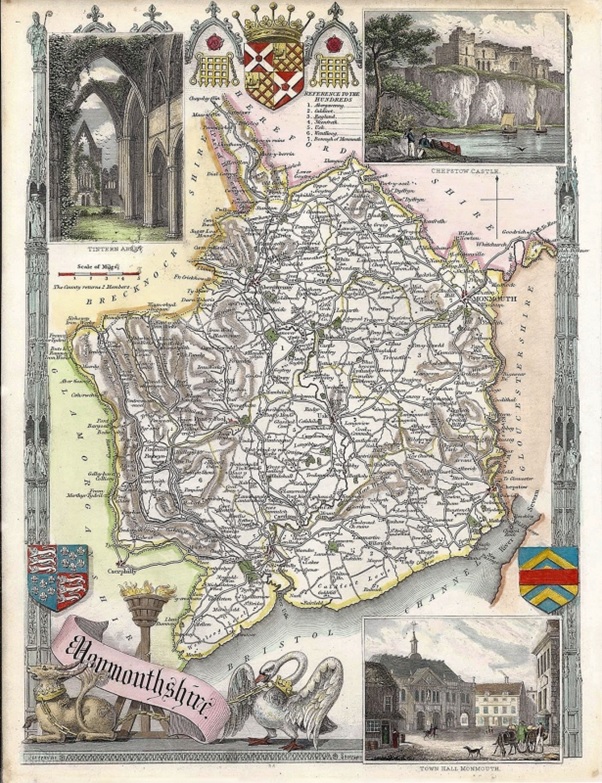

Even as recently as the 18th century, this map, the ‘Hundreds of Monmouthshire’, fails to depict Newport in any way at all.

Instead, it concentrates on the picturesque views of settlements along the Wye Valley – the county’s border with ‘England’.

But by opening the timeline vault on its past today, I aim to produce enough evidence to substantiate my claim that Newport is the true cultural and linguistic capital of Wales!

Or perhaps the area in the present-day Newport’s immediate vicinity, since for centuries the wide, impenetrable mud flats and marshlands on the banks of the Usk precluded a settlement of any size.

It is rather at Caerleon, two miles to the north of Newport’s present-day centre, that the culture familiar to everyone today as ‘Welsh’ took shape.

Here I acknowledge the work of James Mathews, Newport Public Librarian for over 30 years from 1875, who catalogued Caerleon’s – and Newport’s- early histories.

Of Caerleon, he argues that “it is questionable whether any city, town or place in the British Isles can claim an earlier date when Christianity was first made known”.

With the gradual breakdown of Roman Civilization in these islands, he argues, Caerleon became in effect the Capital City of ‘Britain’.

A city where the language evolving into Welsh – a mixture of latin and Brythonic – was very much in a majority.

New port

In the 5th or 6th century Gwynllyw, patron saint of Newport, united most of the area to the east and west of Caerleon. This is the area which is now more or less bounded by the M4 motorway and the sea.

His name peppers this same area, mostly in the mutated format of Wentloog, Pillgwenlly, St. Woolos, Wentwoods, and Gwent itself. It is arguable that this single Welsh root provides the strongest cultural identity for the present-day population.

Mathews names ‘Pendan’ or possibly ‘Pyndan’ as being the original Welsh name of the original settlement on the Usk mudflats.

There is no mention of it in the Domesday Book, but after the Normans came they were not long in bridging the river, constructing a castle – tiny by their standards – and rebuilding Gwynllyw’s church.

The bridge signalled the effective beginning of a new town, Caerleon’s ‘outport’ no less, though it is not at all clear as to when the word ‘Newport’ was first used.

Battle

What followed was a struggle over Newport’s identity over the following millennium.

Place names such as Allt-yr-yn, Maesglas, Crindau, Glasllwch, Bettws existed and indeed still do.

But the incorporation of Wales into England in 1535 and subsequent creation of ‘Monmouthshire’ as an English county could very well have spelt the end of Newport’s ‘Welsh’ existence.

That it did not is a testament to the strength of Newport’s Welsh character.

Writing about the National Eisteddfod held in Newport in 1897, J. Gwynfor Jones notes the following:

“Whatever its impact may have been on Welsh consciousness, it is clear that attention was drawn to that remarkable phenomenon, the survival of the Welsh spirit and language in even the more ‘anglicized’ parts of Wales.”

Over the following years Newport was at the centre of some of the events of most significance to Welsh history, identity and culture:

- The massive immigration from both rural Wales and England into Newport and its industrial hinterland in the 19th century

- The Cymru Fydd meeting held by Lloyd George in the town in 1896 that effectively halted the movement in its tracks

- The victory by a Welsh rugby team containing a core of genuine working-class men against England for the first time in January 1897.

Bourgeoisie

One of the most important of these events in shaping the character of Newport was the unveiling of the civic War Memorial in 1923.

Almost 1,500 Newport residents died in and as a result of the First World War.

Although it perhaps inappropriate to speak of it in such terms, a battle followed over whether Welsh in both language and sentiment was to be included on the cenotaph memorial erected at the entrance to the town via the Chepstow Road.

The South Wales Argus reported that the unveiling ceremony itself was performed by Lord Tredegar and that the presiding officer was Lord Treowen.

It is here that the Welsh connection is strengthened for this Lord Treowen was the grandson of Augusta Hall – Lady Llanover herself – perhaps the greatest champion of Welsh culture in the modern history of Newport and its county.

Tragically, Treowen lost his son Eilydr in the war and a breathtaking memorial to both him and the men of the Llanover area was built by his father.

It just could be that in the aftermath of the unveiling, the subtlest of pressures were applied by Tredegar and Treowen against the Newport bourgeoisie who, years earlier, had shouted down Lloyd George’s ‘Cymru Ffydd’ Welshness.

Letters from Tredegar and Treowen to a council meeting on 15 September 1923. A Welsh inscription on the memorial soon followed.

This then is my theory on how social classes came together to confirm the essentially Welsh identity of Newport.

Get off the train today and bilingual signs are everywhere. It is a short walk to Capel Mynydd Seion and a fully comprehensive Welsh secondary school prospers.

Just be careful inspecting the Memorial though – it is right in the middle of the road!

Nation.Cymru is currently fundraising to pay for independent journalism. Just £2 a month by 600 people would achieve this – please click here for details.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.