On being a poet in Wales: Roberto Pastore

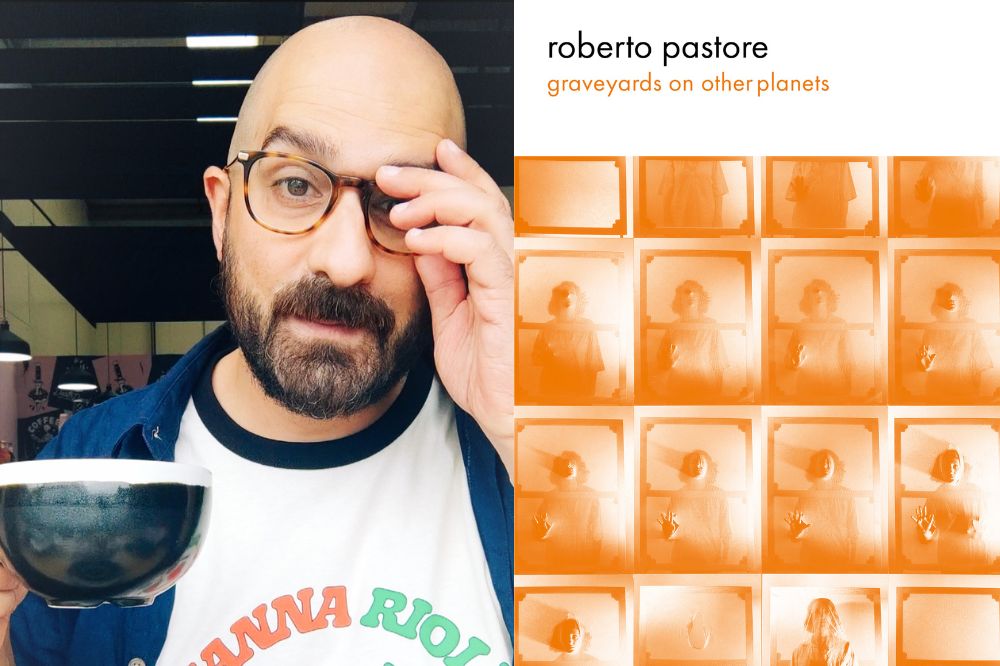

Roberto Pastore

In the days when writing poems still felt new and vital and physical to me, I would sit in my room in Carlisle and fill up notebook after notebook without any thought of craft and without shame, or praxis, and certainly no thought of audience. There was no fear of the blank page. I just wrote; it was so easy. I made note of the slow changes and rotations of each season and the always unresolved hum of traffic outside, and even though it often felt as though life itself was passé and amounted to approximately nothing, there was always plenty to write about. There was nothing better than chasing the phrase or word combination that felt most alive and true, even if it wasn’t always actually true, the right line would feel truer than the real thing if set down correctly, with intention.

Like any new addiction it felt like a secret I’d stumbled onto; something precious but also degenerate. Whatever that feeling was I knew I was only borrowing it; that it had something to do with being a stranger, a novice, young, a little lost, deluded, tender, wired, bored, and that it wouldn’t last. Through the sealed windows I’d see people who didn’t know or care about my secret but who were living proper lives with places to go, pass on their way to those places, all forward momentum while I hung suspended in my loneliness.

I don’t miss it. But I do miss the arrogance of the new addict; in Buddhism they call it ‘beginner’s mind’. It’s a mortifying but aspirational state, like anything pure. I lost it somewhere in Wales, probably Llanhilleth in the big fog. I found other more urbane pleasures; I read the theory books, the biographies of great poets, looked into form and composition without much commitment, toned down the hammy Americanisms and all the stuff about bodily fluids in favour of something cagier that maybe didn’t feel as honest but felt less vulnerable. Shame crept in, and life. You make concessions to the world you gather up around you – it no longer feels like a backdrop, but the real thing.

Collective

In Wales I stopped feeling so much of an outsider. There’s something about this place that is undeniably collective. I know stereotypes, even those we embrace, are reductive and cheap but you can’t help reflecting on the years of working-class resistance, of unionised solidarity that make up the psychological stratigraphy of Wales and see the current rise of Reform as a failure of spirit. I celebrate the Wales of R.S. Thomas’ ‘foot-rot and the fat maggot’, Cate Le Bon ‘writhing in the reeds’, the bruisy heaviness of Josef Herman’s Evening, Ystradgynlais, Icons of Filth singing their anti-nuclear dissent; ‘You’re better active today than radioactive tomorrow’.

So how do we write now? How do we express these times? Why bother with poetry in the face of genocide, pandemics and authoritarianism? Do we have a responsibility? How do we continue to tend to the project of the future? For four years I hosted the Lufkin Poetry group here in Cardiff, and these were questions that arose, or at least they did for me. Good, serious questions. Here are some thoughts I’ve come to over recent years. Poetry has no responsibility to offer answers. I reject poetry as a vehicle for ideology. Poetry shouldn’t feel like propaganda, but it should be engaged – politically, morally, emotionally, but also with pop culture, trash, the vernacular. I’m immediately put off by poetry that tells me only what I already know or feel, as if seeing my own views reflected back at me on the page or in a room full of people (who also feel the same way) is anything but complacent back-patting. I see that as a minimising of poetry’s function.

Poetry should always strive to get beyond the initial, most obvious response or thought. I always say to poets just starting out, if you feel the urge to write about something, whatever it is, disregard your first thought because it will almost always be the product of conditioning – write it down anyway, but then forget it. Aim for the next thought, and the one after that, and so on, until you reach the thing that you couldn’t have got to without the poem itself. In other words, what comes after the cliché? The poem will tell you what it wants from you. A poetry whose sole purpose is to espouse a system of belief, even your own, is a misunderstanding of poetry’s parameters. Poetry is bigger and more unwieldy than that, just as we are.

Syntax

I’ve met many warm, kind, engaged poets in what might loosely be called the local poetry scene here in Cardiff. They attend book launches, host poetry workshops, perform at open mics, teach, uplift each other and put their energy into it. I should probably put more effort in. Because I also feel welcome here. Go to a poetry reading now, you can feel it in the room, the need for each other. Remember that listening is a form of care. Deep listening is the covenant between the poet and the receiver. Paying attention to someone’s changes, to someone’s rage, maybe someone who doesn’t have anyone else in their life who will really listen. It’s a trip that we get to perform that kind of care.

So, as a kind of answer to the questions I asked earlier, how do we write in and of our times; we pay attention, to the hour and to ourselves. Louis Zukofsky expressed the writer’s task as that ‘of isolating the mutations and implicit historic metamorphoses of an era’. When we are present to what life feels like, right now, this morning, the writing can’t help but contain something of the era. The tone and tenor of the moment are indivisible with the mode of the poetry, the attitude, the choice of words; it’s in the air so you can’t help but breath it. John Giorno said something like: the way you know you’re dead is you breathe out but can’t breathe back in. The great Welsh poet Lynette Roberts wrote ‘I follow the death that stands on my breath’.

The breath is syntax, and the task of the writer (and reader) is to find the syntax that feels most natural to them, the one that feels closest to your own weird unreplicable BPM, taste, internal voice. Maybe beginner’s mind is a recurring state and we’re perpetually making small breakthroughs, dismantling preconceptions, always starting over, from scratch. I feel like that today, with this new collection about to hit the shelves and find its way into people’s bags. I began writing Graveyards On Other Planets with some pretty lofty goals and intentions. Then I remembered how to write like me. And to allow that. It was like being back in that small room in Carlisle again, except with the windows wide open. My copy arrived this week, I open it and there I am, each one of me, messy and multitudinous, breathing out.

Roberto Pastore’s sophomore poetry collection Graveyards On Other Planets is available from Parthian Books.

Roberto Pastore is a poet based in Cardiff. He studied Art History & Creative Writing in Carlisle where he was part of the renowned Speakeasy spoken word scene. His first collection Hey Bert (Parthian, 2019) was highly commended by the Forward Poetry Prize and subsequently appeared in the Forward Book of Poetry 2021. In 2022 he released a poetry pamphlet entitled Absolute Joy which led to a collaboration with artist Rob Churm. Graveyards On Other Planets is his second full collection.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.