On Being a Writer in Wales: David Llewellyn

David Llewellyn

Like many writers, I’ve always had a fondness for libraries. My first in my hometown of Pontypool is a lovely, musty old building near the grand Italian Gardens entrance of Pontypool Park, one of my earliest memories is of leaving behind a beloved stuffed toy, and the nice ladies there looking after it.

Through Primary School I graduated from Roald Dahl and Beatrix Potter to abridged versions of gothic horror, and later Stephen King. By my mid-teens, I was borrowing Hanif Kureishi’s The Buddha of Suburbia, having seen the television adaptation, developing a massive crush on its star Naveen Andrews.

Around the same time, from the library at Abersychan Comprehensive I took, and kept, a copy of Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, thinking I might one day write a novel set in the Gulag, a good quarter-century before the publication of A Simple Scale.

Dartington College of Arts’ library was cavernous, spread out over two storeys, with a small VHS video player and TV, on which I saw Fassbinder’s Querelle for the first time. I also borrowed a copy of Kathy Acker’s Blood and Guts In High School, one that still graces my bookshelves to this day.

Idols

The books which had the most profound and lasting effect on me were those by Derek Jarman, Dancing Ledge and At Your Own Risk, which opened up a world of creative possibilities, allowing me to become better acquainted with one of my filmmaking idols, whose work I’d seen on Channel 4 following his AIDS-related death in 1994.

I’m old enough to remember three iterations of Cardiff Central Library, from the space-age one in the original St David’s, and the temporary cabin on Bute Street to its splendid modern incarnation, a remarkable public space, opened by the Manic Street Preachers in 2009.

This was also the year when I met my partner Dan, an artist who works in the Cathays Heritage Library on Crwys Road, and in recent months, we’ve acquired a lovely new local library and coffee shop in the former chapel of Cardiff’s Royal Infirmary, a regular writing spot whenever I’m feeling cooped up in the confines of my own home.

Breakfast with the Gladstones

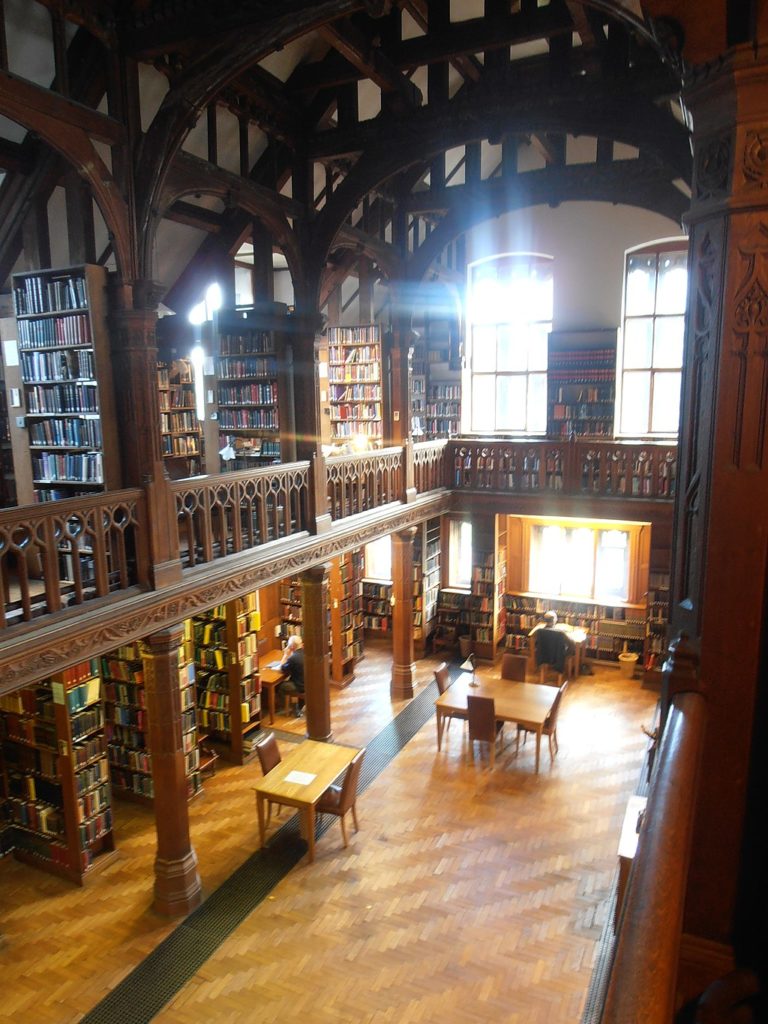

I’d heard of Gladstone’s Library long before staying there for the first time, back in May of this year. I’d seen others, including fellow writers Damian Barr and the historian Rebecca Rideal mention it, and the photos made it look splendidly Borgesian, with its multiple levels, niches and nooks.

Dan’s mother Bev read about it in a travel supplement, and thought it would be the ideal holiday destination for us. She has family in North Wales, and so it would be an opportunity for us to visit her elderly aunts, combined with a stay in one of Britain’s most splendid libraries.

With our train network hamstrung by the swingeing cuts of yesteryear we set off from Carmarthen by car, winding our way northeast across the Brecon Beacons. This was my first proper visit to this part of Wales, until now I’d only passed through it on my way to Liverpool via Chester or Crewe.

Our brief stay was wonderful. We spent much of our first day exploring the library and its environs. In the Theology Room I saw people tapping away at laptops, wishing I’d brought my own along for the trip.

I’m an early riser, and so I’d often get up before Dan and Bev, going for dawn walks around the gardens and the graveyard of nearby St Deiniol’s, to watch the sun rise over the sprawling flatlands of Deeside, the morning dew still frosty from a clear and chilly spring night.

Bewitching

No sooner were we back in Cardiff than I began planning my next stay. I’d found the churchyard and the grounds bewitching in high Spring, but knew they would be even more magical in Autumn, a time of year when I’m often desperately in need of something to look forward to.

From August till October I’m the short film programmer for the Iris Prize LGBTQ+ film festival, an intense but enjoyable few months, with a chance to watch films, talk about film, and meet filmmakers from around the world. This year, for the first time since 2019, we were able to have international guests again, bringing some familiar faces back to Cardiff.

After the highs of the festival come the months of searching for another decently paid gig. Freelance life is precarious at the best of times, but in Autumn and Winter it’s desolate. My finances always take a hit, my mental health struggling as a result, worsened by the shorter days and dismal weather.

I knew I needed something to keep my mental health in check, and so I booked myself three nights in a single room, using my Society of Authors discount, promising I would spend the time writing and reading, relaxing in peaceful surroundings, and allowing myself time to think of practical and productive ways to cope during the fallow months to come.

Throughout my time on the Iris Prize I was also working on a new novel, The Trefoil Affair, which began life in 2020 as a fictional oral history documenting events at an all-girls arts school in Carmarthen during the 1940s.

This draft was 30,000 words long, short and punchy, but it was only the scaffolding for a story, written in haste to get something finished while the idea was still fresh. I read this to my partner in a log cabin near Llansteffan, where the book is set, in January 2021, and immediately sent it to my agent, Nemonie Craven.

It was she who suggested working the idea up into a more conventional novel, and we discussed this further over the following months.

Characters who were once thumbnail sketches came to life, scenes mentioned briefly in passing became key dramatic moments, taking us from the worst of the London Blitz to the wartime Royal Academy Summer shows, post-liberation Paris and parties at the Dorchester.

Deep dive

To recreate the world of 1940s Britain and beyond I began reading up on World War 2, and doing a deep dive into everything from fashions and the realities of life in London during the blitz to the music of the day and political events and historic events as they unfolded. Verisimilitude is vital in historical fiction, especially when there are elements of fantasy.

By the time I got to Hawarden, after a circuitous train journey via Shrewsbury, I’d written almost 60,000 words, and was barely two thirds of the way into the story I’d mapped out back in January 2021.

As soon as I’d checked in, dumping my luggage in my room, I took my laptop, reading glasses, headphones and a bottle of water to the Theology Room, the heart and soul of Gladstone’s Library.

In May I’d looked at the scholars, writers and members of the clergy working away with envious eyes. Now, five months later I was climbing the narrow, creaky stairs, holding onto the rope for dear life, and searching the top deck for an available desk.

Whispers

It’s the silence you notice first. No-one speaks, the only sound the gentle tapping of keys or muffled sounds from the corridor, and the occasional church bell. Queries are spoken and answered in whispers, and one feels self-conscious zipping and unzipping one’s bag.

Once everything was set up, finding a plug point, turning on the overhead light, and putting everything square I was ready to begin. I’ll often visit coffee shops with good Wi-Fi and plug points, or public libraries back in Cardiff, but absolute silence was what I needed for the next chapters I would write.

One sequence in particular, in which a key character dies, was something I’d been dreading for weeks while working on the novel at home. It needed time and focus to do it justice, to get the tone and the style of it just right, and I took frequent breaks, to gather my thoughts and steel myself.

If I was still a drinking man I’d have gone in search of a single malt to take the edge off once I’d finished writing those scenes.

Three months sober, I instead bought a hot chocolate and went straight to the Gladstone Room to read some more of the British Library collection Evil Roots: Killer Tales of the Botanical Gothic, which has been one of my mood board books for the work in progress, alongside films such as Małgorzata Szumowska’s excellent feminist folk horror The Other Lamb.

Political cartoons

Gladstone is everywhere in the library bearing his name, in the form of busts and statuettes, and delightful political cartoons in frames. He’s there in his words, too, with choice quotes framed on the corridor connecting the theology room and the library’s restaurant.

The irony of staying in a library founded by one of Britain’s greatest Prime Ministers, and a liberal, at this moment in our history became a recurring feature of many conversations I was part of, or overheard, few of them flattering about the recent incumbents. Gladstone may be long dead, but his words, his ideas and his library will long outlive all those who follow in his footsteps.

My writing routine was quasi-regimental; rising early, wandering around the churchyard or the grounds, or sitting and reading in the Gladstone Room till 8am, when the kitchen’s shutters came up, revealing the delights of a continental breakfast.

There are more cartoons and statuettes of Gladstone in the library’s restaurant, and one morning I found myself seated next to a charming illustration of William and Catherine Gladstone taking tea outdoors at Hawarden Castle, feeling that I was in very good company.

Suitably fed and caffeinated I’d go to the library, find my spot, perhaps one different to the day before, and start writing again, working on some of the most emotional chapters in the book. For these I donned my headphones, listening to the appropriate music to help me set the tone.

Playlists

Some authors, notably the irascible Philip Pullman, hate the idea of listening to music while writing, saying that it pays too little respect to the music question, but some of my best writing has been done with music playing in the background, and I’ve made entire playlists for specific projects.

For The Trefoil Affair I needed something suitably melancholy and stirring, settling on a playlist called ‘Dark Academia Classical’, its description reading, “Quiet hallways, dusty sunlight, cosy sweaters and hot tea.”

The theology room offers a delightful snapshot of the people who visit and use Gladstone’s Library throughout the year. I saw at least one clergyman, and countless students of history, politics and theology, many of them half my age, all hard at work, often until the library closes its doors at 10pm.

Working there in the twilight hours, the wind buffeting the windows and a distant church bell marking each passing hour, I couldn’t ask for a better place in which to write a gothic thriller set in rural Carmarthenshire.

While walking around the corridors and stairwells of the library you get to recognise certain faces, exchanging good mornings and hellos.

When a waiter in Food for Thought mistook me for another bald, bearded, spectacle wearing gentleman, giving me his curry, and not my goats cheese salad, he and I spent the rest of our time there grinning at one another whenever our paths crossed.

Encounters

One morning, while waiting for breakfast and coffee, I got talking to Heather Thelwell, a Canadian cheese connoisseur who came to this part of the world to visit family, and experience Britain’s only Prime Ministerial library.

She and I bonded over a mutual need for good coffee first thing in the morning, and had breakfast together, talking about each other’s work and our love of libraries.

Our fast friendship was to be short-lived, though we may meet again – the world is funny like that. Later that morning I saw her getting into her cousin’s car, her time in Hawarden at an end. After visiting an elderly aunt she was setting off for Pembrokeshire to visit its many independent cheesemakers.

It was just another of those brief but memorable encounters that can only happen in a place like Gladstone’s Library.

On my second night I hopped on a bus to Chester, instantly wishing I’d caught the train, as it bumped and rattled its way along the roads. I arrived in time to grab a coffee at Caffé Nero, a five minute walk from Chester Cathedral.

Before settling down to wait for evensong I lit three candles, one for my mother, one for my Auntie Margaret, and another for my friend, the writer and educator Philip Wyn Jones, all of whom would have enjoyed a night of choral music in such a beautiful setting.

My mother and aunt were born in Blaenafon and both fine singers, Margaret performing in a women’s choir well into her retirement years.

Stained glass

Philip, a lifelong film buff and Hitchcock devotee who I met through the Iris Prize, was a regular attendee of the Three Choirs Festival, sending me postcards from Gloucester and Hereford.

Though I’d probably describe myself as an agnostic, I have a lifelong love of sacred buildings and stained glass, and find the medieval gothic cathedrals of Europe fascinating. An innovation of the 12th Century, their tall, tapered windows and fan vaulted ceilings hint at the influence – and perhaps involvement – of Arab stonemasons during the time of the Crusades.

The visiting choir, from Harrogate’s St Wilfrid, sang beautifully, their voices soaring into the Cathedral’s upper reaches, inviting the listener to look skywards, as if that were the music’s source. Those medieval architects understood the spiritual power of acoustics and light.

Staying till the very end and stopping to thank Rev. Tim Stratford on my way out made me late for my booking at Blue Bell 1494, a tapas bar in one of the city’s genuine Tudor-era buildings. Fortunately, they were still able to squeeze me in, on a table in the heated garden and the food was sublime.

Killer tales

I was too late getting back to Gladstone’s Library to make use of the theology room, and so I retired to the Gladstone Room, reading some more “killer tales of the botanical gothic”, and called it a night.

The following day I rose early, waited for breakfast, and made the most of my last full day in the library, working through the morning, afternoon and evening, until late, when there were only a handful of us night owls sitting in little pools of lamplight and the glow of laptops on both sides of the Theology Room’s upper tier.

On Thursday I checked out after breakfast, handing over my luggage and key fob at reception. Via a whispered conversation with the librarian I acquired a temporary pass to the Theology Room, so that I could carry on working through the morning and early afternoon.

At some point during the day I lost my Bluetooth earphones. Not a problem, I thought. I can always read my book. How wrong I was. The first half of the journey was nightmarish. Without music in my ears the bus rattled and clattered and shook its way to Chester.

The train out of Chester was packed, and I found myself pressed against the window by a fellow passenger who promptly fell asleep. The air conditioning wasn’t working, and the windows were shut, making the air unbreathable.

Anxiety

I’d gone from the peace and tranquillity of Gladstone’s Library to the noise, heat and discomfort of an overcrowded train full of people talking at full voice and before long I was in the grips of an anxiety attack, crying and hiding my face from the other passengers.

After an hour of this they opened the windows, and the train started getting quieter from Hereford on. My nearest neighbours were a young father and his daughter, playing games on some device. The panic attack subsided, but left me shaken, and I got on with reading my book, relieved to find that in no time at all we were passing Abergavenny and Cwmbran.

Beyond the train’s windows, across Britain’s darkling plains, Rishi Sunak remains our de facto Prime Minister, while his Home Secretary Suella Braverman travels from London to the internment camps of Dover not by train but in a dystopian black Chinook.

It’s comforting to know that long after those in power have become the stuff of footnotes and appendices, Gladstone’s bust will still welcome guests as they climb the creaky staircase to the bedrooms, the kitchen will open at 8am sharp, strangers will meet one another in the Gladstone Room, and scholars, writers and members of the clergy will forever be found working by lamplight in the monastic silence of the Theology Room.

As I was leaving Gladstone’s Library, my heaviest bag on my shoulder, a long journey from one end of Wales to the other ahead of me, I took one last look around the place, taking in some of Gladstone’s quotes, singling out my personal favourite.

“The principle of liberalism is trust in the people qualified by prudence.

The principle of Conservativism is mistrust of the people qualified by fear.”

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.