Port Talbot is a crucible: Jon Doyle on writing faith, masculinity and the weight of a place

Gosia Buzzanca

Each year at the end of January, The Observer selects its list of the best debut novelists. It is the announcement I look forward to reading, because among the authors and books selected, there usually ends up a novel with the potential to become my favourite read of the year.

It is also thrilling to see a familiar face there. Last year, The Observer selected Anthony Shapland’s A Room Above the Shop, which went on to soar in praise and readers’ hearts.

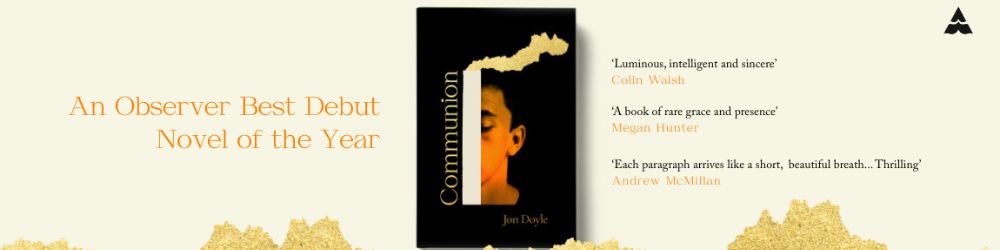

This year, Port Talbot’s own Jon Doyle has been selected for The Observer’s list.

His debut novel, Communion, is, according to the paper, “sparely told yet brimming with big themes – faith, masculinity, activism.”

Jon was kind enough to answer some of my questions about it over the weekend.

Your debut novel, Communion, is rooted in Port Talbot. What drew you to setting your debut there, and why did it feel like the right place for this story?

Port Talbot is my home, though I resisted writing about it for a number of years. Maybe because the familiar doesn’t seem exciting? Or else I didn’t want to be one of those young authors who writes a thinly veiled version of their own life.

But I found everything I worked on lacked something. I don’t know, call it authenticity. And the more I thought about it, the more I came to see Port Talbot as something of a crucible for the themes I found most interesting.

The ongoing struggle with the steelworks felt like a microcosm of the wider situation the world finds itself in. There’s a tension between the past and the future. A general confusion. A mistrust of promises.

Port Talbot is often spoken about through stereotypes. Did you feel a responsibility, or perhaps resistance, to the existing narratives while writing your book?

The images of Port Talbot are contradictory. On the one hand it is seen as this dirty, gloomy place people drive past quickly on the motorway. On the other, a place with rich cultural history that has given the world Richard Burton, Anthony Hopkins and Michael Sheen.

I think it’s natural for a person to be resistant to both positive and negative stereotypes, not wishing to see their home or themselves flattened into something overly simple. But equally stereotypes can be useful, even attractive.

Isn’t local pride, for example, on some level a simultaneous rejection and embrace of stereotypes? Likewise, if masculinity is an important theme in Communion, then it’s about how a man is expected to live up to certain expectations.

I deliberately had my protagonist Mack struggle against the weight of various stereotypes, be it as a working class man or a man of faith. The backdrop of the novel, a fictional reimagining of Sheen’s Passion, allowed me to play with this idea.

The roles we are asked to play. The sense of performance within any sense of identity.

How important is place to you as a novelist more generally?

Place is as important as anything else. Each element of a work informs the rest. The characters of Communion would be different if they were not from Port Talbot.

But equally the picture of Port Talbot might look very different had I told it through different characters. The important thing is harmony. The sense that all of the moving parts of a novel are working together.

Being selected as one of the Observer’s best debuts is a big moment. How did that recognition affect you?

I was delighted, of course, and a little stunned. A writer can work for years with no apparent progress, at least in terms of their professional career, and then suddenly things start happening all at once.

I try not to take anything for granted because I know how difficult it is to break into the industry in the first place. There are a hundred talented debut novelists who were overlooked for that particular list, a thousand more who haven’t even managed to get their novel published.

I’m incredibly lucky to have found a home for my work at all. It feels like an opportunity I want to grasp while it’s there.

What was the biggest challenge you faced when writing your first novel?

Communion might be my debut novel, but as with most authors, it wasn’t the first I had written. The biggest challenge is to persevere through knockbacks and disappointments, to motivate yourself and continue to develop your craft without validation from outside.

Writing a novel can be difficult enough, but trying to start again the day after your previous attempt was roundly rejected is another matter entirely.

You have to have a certain stubbornness, I think. Plus a desire to do the work for the sake of the work alone. Recognition is nice, but not the end goal. More a means of being able to continue my career.

Did your upbringing in Wales shape your sense of what stories felt urgent or worth telling?

Certainly. Port Talbot is a strange place because in many ways it feels like a pocket of industry within a wider post-industrial landscape.

We can see where the neighbouring communities were left after their main source of employment was removed. Which means the stakes are all too apparent as we watch global corporations make huge decisions with barely the blink of an eye.

I walk past Dic Penderyn’s grave most mornings. None of this is new.

But equally I’m all too aware of the environmental cost of this mode of living. The steelworks are a massive source of pollution. Coal must be left in the ground. Even the rolling green hills of Welsh postcards are essentially barren.

The most urgent stories of today are those which grapple with these competing facts and how they are tied up in Welsh identity. Workers and communities cannot be left behind, yet we cannot ignore the emergency of the present.

How do you see your work fitting into contemporary Welsh writing today?

I’m proud to be a part of this exciting new wave of Welsh writing. The likes of Cynan Jones, Sophie Mackintosh and Tom Bullough have led the way, while the arrival of things like Folding Rock magazine has been a breath of fresh air.

I was part of a Literature Wales scheme called Representing Wales a few years ago along with Anthony Shapland, so watching A Room Above A Shop win such acclaim has been great.

That Representing Wales cohort alone was packed with talented writers. Alex Wharton, who continues to take children’s literature by storm, but also people not yet published like Ben Huxley, Rosy Adams, Simone Greenwood, Hattie Morrison, I could go on.

The future of Welsh literature is bright, it just needs adequate support. You only have to look at countries like Ireland to see what happens when artists are valued.

How do you approach writing about working-class communities?

I approach it the same way I would anything else. My uncles were steelworkers, my grandfathers, my great-grandfathers, the boys I played football with and knew in school.

If there was any difficulty it wasn’t because the community is working class but because it is so close to home. To write a simple celebration or criticism would do a disservice to reality.

Much of the literature marketed as ‘working class’ fiction seems more concerned with an imagined idea rather than reality, be that overly romantic or pessimistic. I wanted to be sincere without being sentimental.

What writers or other cultural influences helped you believe this book was possible?

Talking on a purely artistic level, there are too many to list properly. The likes of Marilynne Robinson, Jon Fosse and Graham Greene showed you can write about faith without ending up on the preachy shelf of a bookshop.

Olga Tokarczuk and Rachel Kushner that you can be political without sacrificing nuance. Eugene Marten how ordinary, flawed men can be written with great energy.

What do you hope readers who come to the book without prior knowledge of Port Talbot take away from it?

This is a good question. Of course, Communion is a work of fiction, so it’s not exactly Port Talbot as it exists in the real world.

But I hope some sense of the town comes across in the sentences. The strange combination of fondness and foreboding that the steelworks represent. Of course I’m just one person in a big town, I couldn’t hope to convey anything other than my own limited view.

But Tom Bullough once told me that if I don’t try to tell the story of Port Talbot, then someone else might. Someone not from here, who through ignorance or ulterior motivation might set the wrong impression.

That seems to me a particular danger for somewhere like Port Talbot, given the current situation, but also applies more generally. Communities being spoken for. Realities simplified. People being told how to feel.

Jon Doyle is a writer based in Port Talbot, South Wales. He was part of Literature Wales’ Representing Wales scheme in 2022/23, and won the Writers & Artists Working-Class Writers’ Prize 2023. He holds a BSc and MRes in Zoology, an MA in Creative Writing from Cardiff University, and a PhD in Creative Writing from Swansea University. Communion is his first novel and is available to pre-order here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.