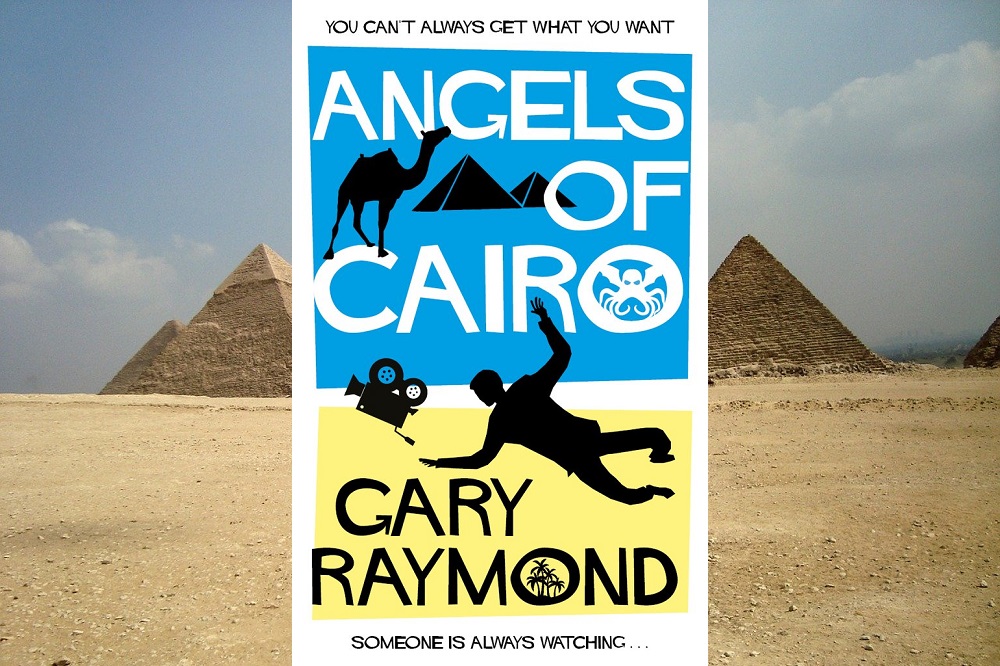

Review: Angels of Cairo is an artfully constructed tale of anxiety and impending doom

Sarah Morgan Jones

Anxiety dreams may find you turning up late to an important event, getting lost on the way, being the wrong side of soundproof glass, unable to break through, or arriving to give an important talk dressed only in your underwear. That helpless, breathless feeling that builds just before you wake in sheer panic is probably a familiar feeling to many.

From the start of Gary Raymond’s latest offering, Angels of Cairo, this lead-heavy anxiety starts to build, slowly and relentlessly, doom impending, as the reader and the protagonist bang fists against a window, trying to be heard.

Robert Clifford, known variously as Rob, Robbie and Cliff, is a debut feature film maker, who has been invited to present his film to be judged at a film festival in Cairo. He begins his wide-awake anxiety dream on the red-eye flight to Cairo, unexpectedly accompanied by his producer’s socially inept nephew, Lewis, “who speaks in diarrhiffic waterfalls” without pause or punctuation, about his own life and embryonic film project. Itching through Cliff’s day, it is completely possible to empathise with his humorous, sporadic and furious urges to tip Lewis over the mezzanine, as the emotionally stunted blatherer makes every part of his day worse.

Relentless

Raymond’s novel, chapter-less and relentless, creates a world in which Cliff is experiencing an existential battle between his heart and his head. His forgettably named film, The Last January, is his weapon against mediocrity; his attempt to be a somebody, to give his time on earth some meaning. He is a man in fear of invisibility. The production process has cost him dearly in his relationships, and the pressure for it to succeed is immense.

By the time Cliff and Lewis arrive at the festival, guests of the flamboyant festival founder, Sammeh, Cliff is already unravelling, a process which accelerates when he realises, he hasn’t actually brought the all-important film with him. This oversight, and the attempts to rectify it, form the dramatic imperative which, along with the infuriating Lewis, drives forward the most important day of his life. Cliff teeters on the edge of control.

Cliff’s back story – of loss, hope and blinkered ambition – is explored against the pre-pandemic turmoil of Trump and global politics; while Sammeh speaks of Cairo in terms of the ongoing repercussions of Egypt’s recent revolution, including a glimpse of his sorrow and pride for his son who fought and died in the uprising. His daughter, Rana, his nephew, and other unnamed family members, form part of his creative empire. Sammeh believes that the revolutionary passion of the youth combined with the wisdom of elders – along with a good western filmmaker, for good measure – offer hope for the future of Egypt.

Tension

The mounting tension throughout the tale, cleverly and wittily managed, is littered by a number of supplementary characters, who carousel in and out of the story, feeling occasionally two dimensional, almost caricatural; they arrive somewhat threateningly and then disappear without the promised ado. They serve to layer up the feeling we share with Cliff, that something is going on – and as Lewis thornily points out, just because you’re paranoid, it doesn’t mean they’re not out to get you.

Some of these characters – a zany Italian documentarian, a femme fatale style, chameleon-esque producer and a right-wing-MAGA-spouting-white supremacist film-maker – arrive with well-formed pen pictures; whereas the various Egyptian women, despite being powerful and professional, are too frequently described in terms of rich flawless skin, deep inviting eyes, mysterious smiles, framed by tightly wrapped headscarves. After several such introductions, the author seems to step in and attribute these shallow observations as a flaw in Cliff’s character – as described by his ever-patient partner, Marie.

The authorial voice makes another unexpected and incongruous appearance, just when the tension is stretched to the limit and we can’t really see a resolution for Cliff: the reader is suddenly noticed and offered the choice of potential endings. Having travelled with Cliff this far, the sudden switch is discombobulating; the proposed endings derail the artfully constructed tension and diminish the impact of the much-anticipated denouement.

The final words are those one would find in a film script, and indeed, this is perhaps its rightful medium. Embellished with character vignettes and a cultural tapestry, the spectacular sights and sounds of a pulsing cityscape, presented on the big screen, would satisfyingly add flesh to the tantalising bones of a good story: a film about a film at a film festival…just as long as he remembers to pack it.

Angels of Cairo is published by Parthian and can be purchased here

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.