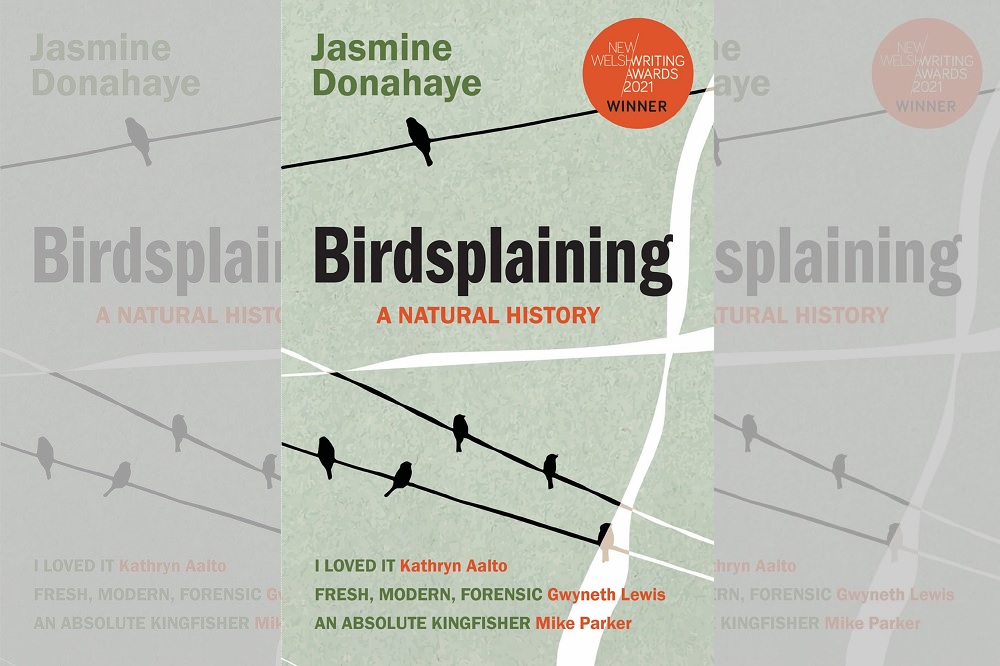

Review: Birdsplaining – A Natural History by Jasmine Donahaye

Lottie Williams

A flock of emotions spark furiously within the essays of Jasmine Donahaye’s new collection, Birdsplaining: A Natural History. Anger, fear and the tragic are skillfully balanced against a curiosity and passion so unapologetically alive that her words form wings and smack you across your face as they take flight, leaving a mark.

Beautifully and precisely written, Donahaye allows you access to an incredibly honest peeling of layers. Feminism and nature abound, these essays are a contemporary fusion of memoir, ornithological and eco writing centred around the reality of being a brown woman in a rural setting and, let’s face it, society in general.

There is a sense of longing and heartache, what ifs and regrets, and Donahaye paints a strong motif of moving from dark to light. As the wren in her chimney escaped from the ash of the stove and ‘flung itself towards the light outside’ she too experiences change, transitioning from feelings of entrapment to enlightenment.

Donahaye questions the notions of space, identity and belonging throughout. She pulls apart various field guides which quietly yet insidiously encourage and bolster existing views of bird-watching being a typically male space. More explicitly white, middle-age and middle-class. She outs many male gazes, from explorers to critics, birders to writers, who embody the given right that it is men who should occupy the natural world.

Intelligence

So what about us? What about the women who ‘seek in wilderness…a space in which we can return to ourselves, rather than a place in which we have to experience hostility and indifference’. I fist pump the air as she reacts to unsolicited advice from stereotypical ‘male experts’. You know, the ones who point the biggest lens. Her annoyance is formulated with intelligence and sharp argument.

She writes about being ‘brown in a rural place’, including the experiences of both women and men. Here Donahaye shines a spotlight on equality, ‘how the right of entry into rural and wild places is not the same for everyone’ and how we can not and must not ‘ignore the experience (and expertise) of people of colour in the natural world’.

She recognises and gives space to several individuals, including an indigenous man called Gemil who provided invaluable support to a white European explorer, but was repeatedly dismissed as ‘savage’. Donahaye highlights this imbalance and the effect it had, and still has, today. Let’s say his name again. Gemil.

Peril

She focuses on the local and familiar, not just the grand and spectacular. What is wildness and wilderness and what can happen if we all have access? ‘Maybe they begin to notice other birds, too, and rivers, and news stories about water companies releasing effluent, or slurry run-off that kills osprey food’.

These warnings simmer throughout. The future of nature (and life as we think we know it) is in peril. The swallows no longer return to her home to nest. Drowned mammalian bodies are floodwater debris. Fires rage in California, painting the sky red. It is heart-wrenching.

I believe these painfully truthful warnings are not intended to shock the reader, rather make us think. Like, really think. Facing the fear of anxiety is needed for action, and this book acts as a timely warning.

How do we continue in these states of uncertainty? How can we look to the starlings that evade a sparrowhawk for clarity? How does a coasting gannet become a spirit animal, providing strength, and ultimately allowing her to feel ‘euphoric and giddy with the endorphin rush of overcoming fear’?

Donahaye can always bring it back to birds. The ‘comical, endearing trundling delight’ of puffins, the ‘spectacular’ ospreys, the ‘churring’ sound of the nightjar, and the ‘swoop and clatter’ of the jackdaws. Heavenly.

Boundaries

Time is just one of many narrative threads interwoven throughout the essays, like a bird building its nest in Spring. She nostalgically recalls childhood moments and old, welcoming bookshops juxtaposed against the horror of domestic abuse and uneasy encounters at sun-down on an otherwise empty path.

With love she writes about her home – her old bwthyn – and its porous walls that provide shelter for wood mice, pipistrelle bats and solitary bees (but not sheep, wasps or slugs – there is always a limit).

She questions the role of barriers whilst at the same time retaining her own personal boundaries, both in nature and human (sometimes she pushes them but there is always a limit).

A curiosity of death is present throughout. An image of the tortoiseshell butterfly is as beautiful as it is alarming, ‘I know they can’t survive, but they batter at the condensation-wet window panes, wanting out into that killing light’. A reflection of her own state.

In acrid detail she describes the ewe’s leg that she finds and takes home, the vivid description of smell evaporating off the page, ‘less a smell than a coating on the air’.

Rather than morbid, Donahaye uses death as a counterbalance to becoming ‘sharply alive’, and it is no accident that the arc of the book begins and ends with her own health.

Understanding

Donahaye is painfully honest and always reflective. She is not afraid to contradict herself when she misremembers facts, or how she herself responds to other humans. She knows that she is being unkind to the woman in the hospital bed next to hers, yet she continues anyway.

She knows that she is judging others in the same way she feels judged by them, but can widen her lens and attempt to fill in the gaps of why people behave in the way they do, ‘exploring birds as a means of understanding social relationships and human relationships to the living world’. Hence the clever title ‘Birdsplaining’, a take on the phrase ‘mansplaining’ in which a male speaks to a woman in a condescending and patronising way.

Towards the end, Donahaye reaches an almost epiphany of her life whilst understanding her sister’s death and giving a huge nod to the wonderful healthcare staff who now stand in her Pantheon. The tone becomes gentler, softer. Kinder, in fact.

It is interesting and enlightening to read how Donahaye reflects and views her identity in the final essay: as a brown woman living in rural Wales; as someone who still bears the metaphorical scars of domestic abuse; as a daughter, a sister, a mother. As someone who absolutely loves birds.

Birdsplaining by Jasmine Donahaye is published by New Welsh Review. You can buy it from all good bookshops or you can buy a copy here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.