Review: Merthyr rhyming – Anonymous Bosch and Ballad of the Black Domain

Jon Gower

Once an industrial powerhouse and revolutionary hotbed, the town of Merthyr Tydfil is the eventful epicentre of both of these new collections of poetry.

Indeed, with literary cartography being all the rage – mapping the territories which writers claim, or continuously explore – you could put a big red pin specifically in the Heolcerrig area as Alun Rees was born there and Mike Jenkins lives there now.

They both share a sense of outrage at the fate of the town and there is a common anger which flickers through their words.

Rees rails against the multiple injustices of the town’s history, stating that ‘When you’re born in Merthyr Tydfil/you’re brought up in grief and pain’ while Jenkins shows us the town as it now is, vivid snapshots of life presented in what is now his trademark demotic of local accents: it’s as if Jenkins overhears the whole town, making of it his own post-industrial Llareggub.

Indeed Jenkins’s verse can collectively be seen a a form of local reportage, a contemporary snapshot of recent events in a town full of people who ‘ewse vapers/ave masses of tattoes’ and ‘even-a churchyard’s full o them druggies.’ So we have the independence march of September 2019 considered through the chatter on a local bus:

‘Well, I dunno, there’s no buses

An-a roads ‘re all closed!’

moans this ol woman.

‘Independence? The driver joins in,

‘ow cun e afford it,

we get more ‘an we put in?’

Trago Mills

The news-in-verse covers subjects such as the possible art work by Bansky in the town, Nigel Farage’s visit to the out-of-town shopping mall of Trago Mills summed up one of the attendees who describes the protestors with their banners including one saying ‘Immigrants Made Merthyr’/with-a loadsa names on,/Italians, Spanish, Irish–/but now they’re takin over!’

There’s the arrival of a new drug, Black Mamba on the streets and the slow disappearance of local characters such as Omo, who has been previously commemorated in verse by Jenkins.

As with so much local news a story can change a lot as it passes person to person as ‘Merthyr Bridge Incident’ attests as ‘tha kerfuffle down by-a bridge’ is pronounced to be someone spraining an ankle trying to commit suicide, then a car driving off the road to a washed up body.

A bus driver turns out to be a reliable source, informing people it was a fisherman who had broken his leg being taken to Prince Charles Hospital.

The poem closes with a couple of locals seeming a tad dissatisfied with the mundanity of the event:

‘Truth is always borin Dave.’

‘Aye, but I bet

Ee wuz ewsin an arpoon.’

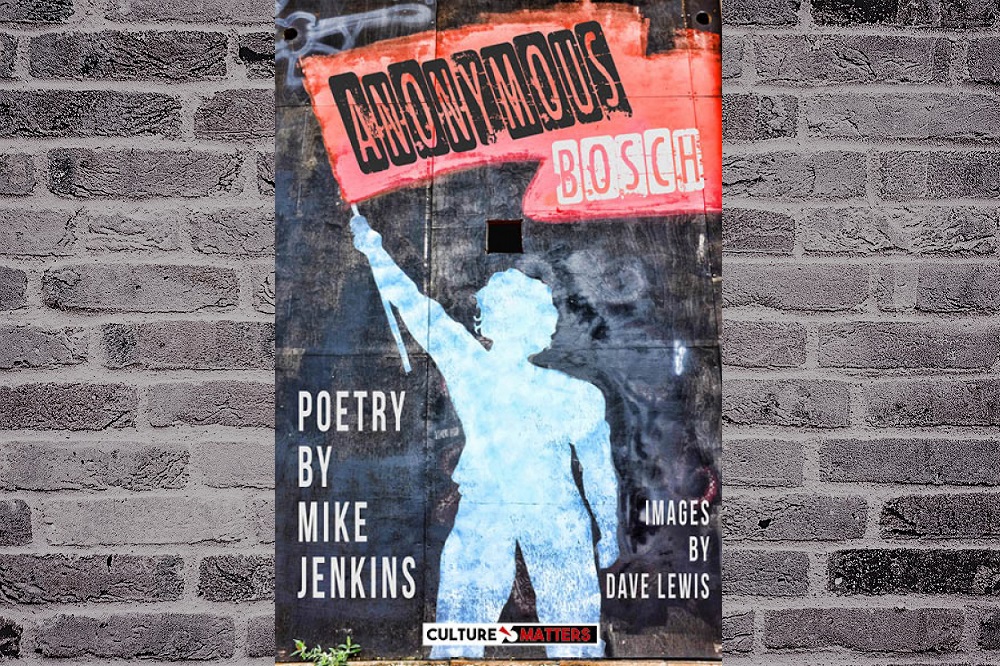

The poems are complemented by superbly arresting photographs of graffiti by Dave Lewis, which meld with the poems and add their own grain of street and underpass, surreptitious artistry and paint-can sloganeering.

Former sports correspondent and newspaper columnist Alun Rees’s valleys are likewise tough, a landscape tensile as the metal that flowed out of Merthyr’s foundries as the poem ‘Steel Butterflies’ attests:

‘This rock-ribbed,

this flinty land,

this land of flinty winds that stone

each day to ragged ruin demands

a fierce love.

Here be violent twilights. Barbed hills

impale a plunging sun

and sacrificial streams

redden the weasel’s path.’

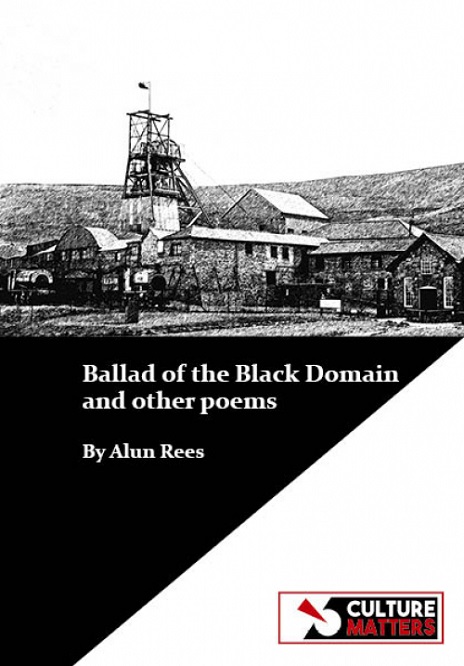

As the long-standing Red Poet charts the ‘Black Domain’ of the south Wales coalfield Rees sees an ‘iron land’ and there’s a staccato run of adjectives that amplify that quality of hardness.

The landscape is ‘begrimed and gaunt and grey.’ Merthyr is ‘brawling and brutal and brash’ and it’s set in a ‘grim world’ where ‘ex-colliers, badged with blue scars’ haunt the streets like their own ghosts.’ Meanwhile the ‘Song of Samaria’ suggests that of all the black spots in the land there was nowhere darker than Samaria, and as Rees adventurously rhymes it, ‘nowhere on earth was scarier.’

The Alamo

There is a searching clarity to Rees’s verse – these are illuminating ballads, heart-felt and true – as he celebrates libraries, the only Welshman at the Alamo or the Merthyr laugh which is a cross between ‘a cracked cackle and a baffled scream.’

The cadences of Rees’s poems are nothing like that unnerving sound but are rather the sound of no nonsense plain speaking, as he rails against social injustice or takes a pop at the arch-capitalist, Lord Baron Merthyr of Senghenydd or turns his withering gaze on the ‘Millionaires’ Row’ of Llandennis Avenue in Cardiff, where the wealthy cower.’

The closing stanza of his ‘Tumbledown Town’ which sing-songs a portrait of a Merthyr which was ‘always in pawn’ pretty much sums up the defiant, unbroken spirit of the town:

‘It’s mucky, it’s messy, it’s tin-tacked together.

It’s a battered old boxer who’s had too many fights.

Yet it survives the worst of history’s weather

through grim chill days and long bitter nights.’

That defiance is there in the staccato, scattergun chatter of Mike Jenkins’ townsfolk just as surely as it is the unbroken backs of the hills which surround the town, where, as Rees puts it the bondsfolk of ironmaster Robert Crawshay ‘were penned on the banks of Shit Creek.’ Two poets’ rhyming and chiming views of one indomitable, revolutionary town.

Anonymous Bosch is published by Culture Matters and can be purchased here.

Ballad of the Black Domain is also published by Culture Matters and can be purchased here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Complete rubbish

This is complete rubbish