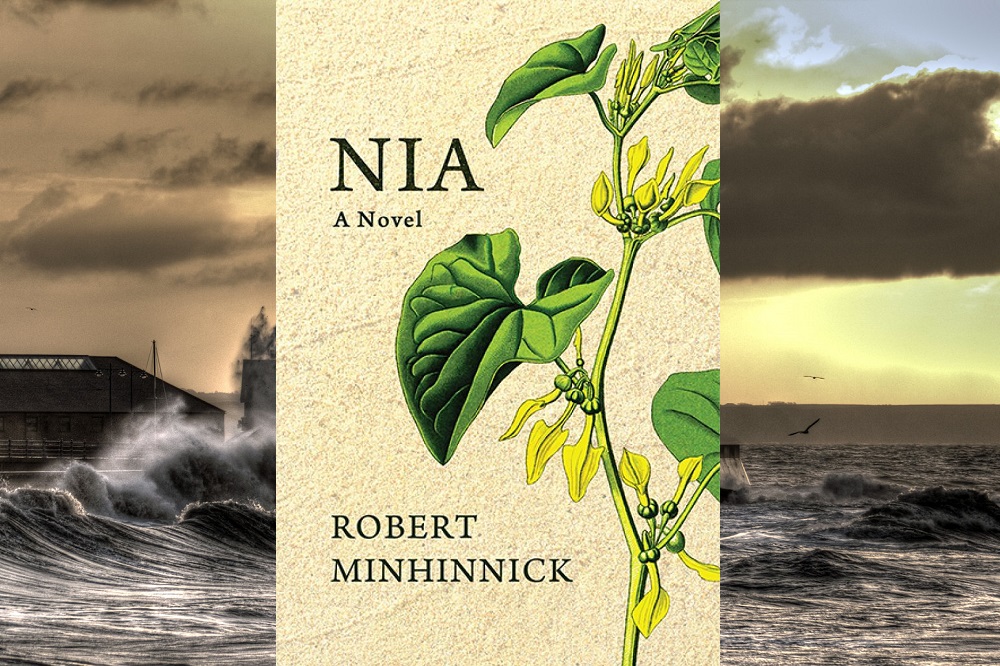

Review: Nia hymns Porthcawl into being

Jon Gower

Some writers write about the places where they live or know to the extent they become synonymous with them, be it James Joyce and Dublin, Kate Roberts and the north Wales slatelands, Proust’s Paris or Gwyn Thomas and what he described as the ‘riven gulches’ of the south Wales valleys. In Robert Minhinnick’s case, his patch of earth is Porthcawl and the seaside town has appeared consistently in his essays, his award-winning poetry and also in a trilogy of novels of which ‘Nia’ is the third part.

Nia Vine runs a shop called ‘Extraordinaria’ in the town, a place not dissimilar to the one Robert Minhinnick and his wife Margaret own in real life or the one a character called Parry runs in Limestone Man, being the second novel in the series. The town itself is changing, with tapas bars spreading along the sea-front – the Paradise Club has become Clwb y Môr – and new and exhilarating rides to challenge a full stomach at the fairground. And here Nia dreams, mental flights bordering on delirium, busily drifting thoughts in keeping with the heat hazes of what is proving to be a very hot summer. She knows this place exceedingly well, not least the sand dunes with their damp slacks and flourishings of orchids.

This was her element. It was her world. She was made of its grit, its gilt, the grains of the coming twilight. She was born into sand and her life was a dream of sand, wind and sand. Yes, harsh this place that never relinquishes its dreamers.

That sense of drift, of impermanence, is there throughout the book as Nia ponders her missing father, the upbringing of her young daughter, Ffresni or her own mother’s lack of sufficient maternal nous. It is not a conventional narrative, with one action setting up another and neither do we get complete and fulsome lives of all its characters. Things drift like the tide, people such as the Lithuanian Rizmas or scrap-metal dealer Isaac Pretty hove into view like ships up a channel. The incidents in the book are often small scale, in keeping with the rhythms of small-town life. Fishermen snag the mother of all conger eels. Someone kills a swan, possibly to eat it. Men with pikes prise sof bodied crabs from rock pools.

Self-standing

Many of the people in Nia’s orbit have seen the world, bringing reports back of life in New York, Amsterdam, Kerala, Poland or Saskatchewan but she feels that she really hasn’t travelled much. Yet she is an explorer, and some of the most atmospheric passages in the book find her deep underground in an unmapped system of limestone caverns where “No-one has been where they are going. Their first twilight was hornblende. Then pitch. The first passageway was easy enough yet solid with sand and silence.”

One of the most striking features about the book is also one of the most expected, being this gifted poet’s deft and delightful way with prose. Nuns are “busy as wrens in their brown habits.” Ice is the colour of “marrow-bone.” Water in a cave is “pittering like a rainstick.” It comes as no surprise that some of the most poetic passages in the book are in fact old poems, refashioned for the purpose, a sort of recycling that seems entirely appropriate in the case of Minhinnick, a lifelong environmentalist and founder member of Friends of the Earth Cymru and Sustainable Wales.

The book leads to an unsettling climax but there is no real sense of a trilogy being finished but rather of possibly an even longer series being set up, of yet another volume in the offing. There are sufficient loose ends to be tied up and minor characters’ lives to be fleshed out and luckily the author himself seems open to the possibility of the series having further life. I for one intend to read all three in sequence, not that you have to follow one after the other necessarily as each volume is self-standing. Together they will surely make a rich kaleidoscope, a lapidary portrait of a town with its gamblers on the slots, buried nunneries, crabsticks and cockle cones, amusement park rides such as The Sunflower, The Kingdom of Evil and The Star Chaser and fairground arcades “loud as battery farms.”

Robert Minhinnick chronicles the drifting life of the place, owns his square mile and seemingly hymns it into being. Nia is yet another fine accomplishment by one of our best writers, suggesting there’s much, much more to come, as if all that ozone-charged and seaweed tanged sea-air truly does invigorate the mind.

Nia by Robert Minhinnick is published by Seren and can be bought here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Sounds marvellous, must buy.