Review: Picture Post: A Twentieth Century Icon

Julie Brominicks

I approached this exhibition with excitement and left it enriched and reflective; in short I’d had an education.

You know the magazine – black and white photography and a snappy red masthead. Yet shamefully, the only image I could muster in advance to have appeared in Picture Post was one by photojournalist Bert Hardy (1913-1995) of two white women in frocks on Blackpool Promenade, published in 1951.

Although it does deliver on a vintage middleclass British aesthetic, this exhibition is about more than nostalgia. Leisure activities and celebrities were included in Picture Post and appear in the exhibition, but the magazine was far from parochial, being international in scope.

Like its overseas counterparts such as Paris Match in France and Life in the US, Picture Post owed its existence to the largely left-wing Jewish photographic innovators escaping Germany in the 1930s.

Co-curator Tom Allbeson, who is available for guided tours of the exhibition on request, explains that the photographers were European émigrés steeped in avant-garde radical politics and that Picture Post was founded by Stefan Lorant from Hungary who fled Germany having been imprisoned by Nazis.

Coinciding with developments in 35mm camera technology, these pioneers developed photojournalism; writing essays with photographs.

Radical change

Reporting on Britain at home and abroad at a time of radical change, Picture Post both documented and influenced its readers. The magazine ran stories about the Second World War, postwar reconstruction, conflicts in Korea, Vietnam and Cyprus, and the disintegrating British empire. It explored racism, multiculturalism, poverty and gender roles, and reflected working-class lives.

Allbeson’s co-curator is Bronwen Colquhorn, senior curator of photography at Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Caerdydd – National Museum Cardiff.

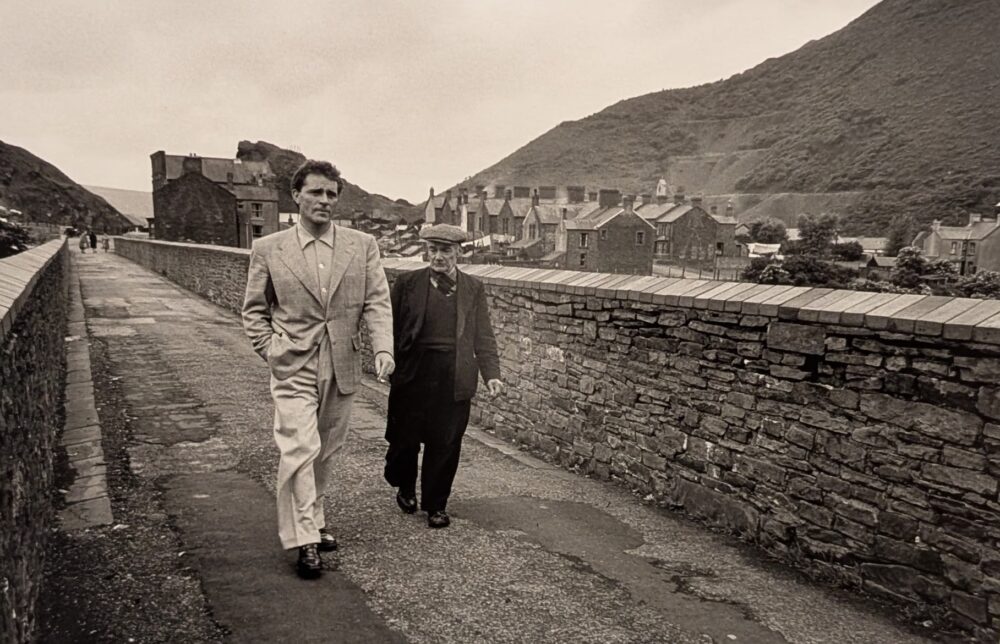

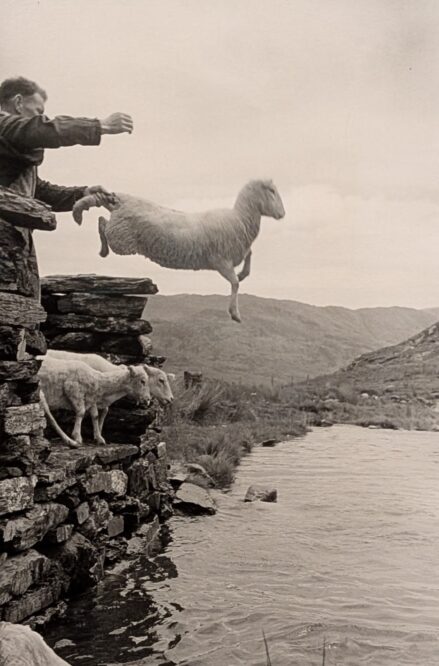

Three-dozen stories about Welsh issues and places were published in the magazine, and Wales is well represented in the exhibition, demonstrating that what Picture Post did brilliantly, was use local stories to illustrate wider social issues.

Butetown, (which along with Cardiff Docks formed part of the area known as Tiger Bay; Wales’s first multicultural community), appeared in a 1952 issue with photos by Hardy. Allbeson, who is a reader at the School of Culture, Media and Journalism in Cardiff, invited Butetown residents to select photographs for the exhibition. Delightfully, the accompanying film of this process features a woman called Gaynor Legall, who is seen dancing in one of the photographs.

Documenting a Welsh multi-cultural community well represented among the exhibition visitors, these images serve to make negativity about migrants from contemporary far-right commentators particularly abhorrent.

Perhaps the Welsh story I found most stirring is “The valley that waits for drowning or reprieve”, which was published in 1957, eight years before the village of Capel Celyn was flooded to become a reservoir. “Liverpool’s plans would end his” reads the text accompanying Alex Dellow’s photographs of Cadwalader Jones who “has bred a pedigree dairy herd, improved land, remodelled his house (and) built a new shed and barn”.

As an English immigrant to Wales very aware of the political and emotional legacy of the valley flooded to provide Liverpool with water, I am somewhat comforted to discover that Picture Post, a London-based magazine, took a concerned interest.

Ephemera including Hardy’s Leica camera and daybooks, negatives and contact sheets, offer a fascinating insight into how skills such as splicing photographs were undertaken manually in a pre-digital world. I’m intrigued by the ledgers in which photographers kept sometimes very brief notes, and by the chipper tone used in the magazine text, which as a writer, I’d have liked to see a little more of.

Opportunities

Indeed, one of the challenges for the curators was how to represent the magazine in a gallery environment. Whereas a magazine is something to be thumbed in private by the reader, framed photographs on public view become art that is not to be touched.

But the challenge came with opportunities, such as featuring “unused” images. While the magazine’s editors chose images that worked together on the page, the exhibition curators selected photographs that stood alone.

With the concise introductory text panels providing just the right amount of context, the curation follows an effective ‘show don’t tell’ approach. The role of women for example does not have its own section or commentary but is a powerful sub-theme throughout, ranging from the photo-story “Should Women Wear Trousers” from 1941, to “Teenage civilian girls are instructed in handling a rifle by an Egyptian soldier” in a Hardy image from 1956.

Today, our visual environment is so dizzy with moving images, we are reminded how powerful a single still photograph can be. The viewer has to imagine the motion around it.

Particularly startling is how these twentieth-century images highlight and give context to contemporary events. ‘A meeting of the British Union of Fascists, at Earl’s Court, London’ by Humphrey Spender in 1939, seems at first to be a Nuremburg rally, until closer inspection reveals the Union Jack suspended above a huge audience. A chilling image given subsequent events, and the current popularity of Reform UK. This exhibition is one that everyone can learn from.

Protest

Post exhibition, the iconic Blackpool image is eclipsed by others filling my mind. One photograph in the ‘Beginnings’ section (title unknown), taken circa 1935 by Austrian émigré Edith Tudor-Hart (1908-1973) piqued my curiosity. It shows Rhondda Valley women on the street with umbrellas and placards.

A little digging, revealed the women were protesting against unemployment and poor living conditions, and that Tudor-Hart was later exposed as a Russian spy. In the Picture Post era, both female roles and the political environment had complexity and depth that resonate today.

Far from being something I saw, enjoyed and forgot, this exhibition has stayed with me long after my visit, inspiring further research and contemplation.

First published in Museums Journal, Vol 125, No 5

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

On the same page here Julie, inspired, I bought a bundle of ten off e-bay to add to the few I have had for years. Nice father and son photo, a similar vintage to me, I suspect my mater may have had a thing for Dic Jenkins’ boy…

Pleased that pioneering photographer Edith Tudor-Hart mentioned, not only for her own work but because she was step-mother to pioneering GP Julian Tudor-Hart – Guardian obit here https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/jul/12/julian-tudor-hart-obituary; Wiki entry with list of JTH publications here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julian_Tudor-Hart

Well well! Thanks for that.

My thanks for the Obit, a timely reminder of the man and the path to take…

And thanks as always to you MM