Review: Skomer Island is a loving account of this jewel in the Welsh wildlife crown

Jon Gower

This doorstopper of a volume might easily be described as Everything-You-Ever-Wanted-To-Know-About Skomer-And-Then-Some and given its weight might be just the thing you need to peg down a tent in a gale. The culmination of a decade’s worth of research by a former warden of the island, it is a painstaking account of its human history, from its earliest settlers to the last of its farmers and of course its natural history.

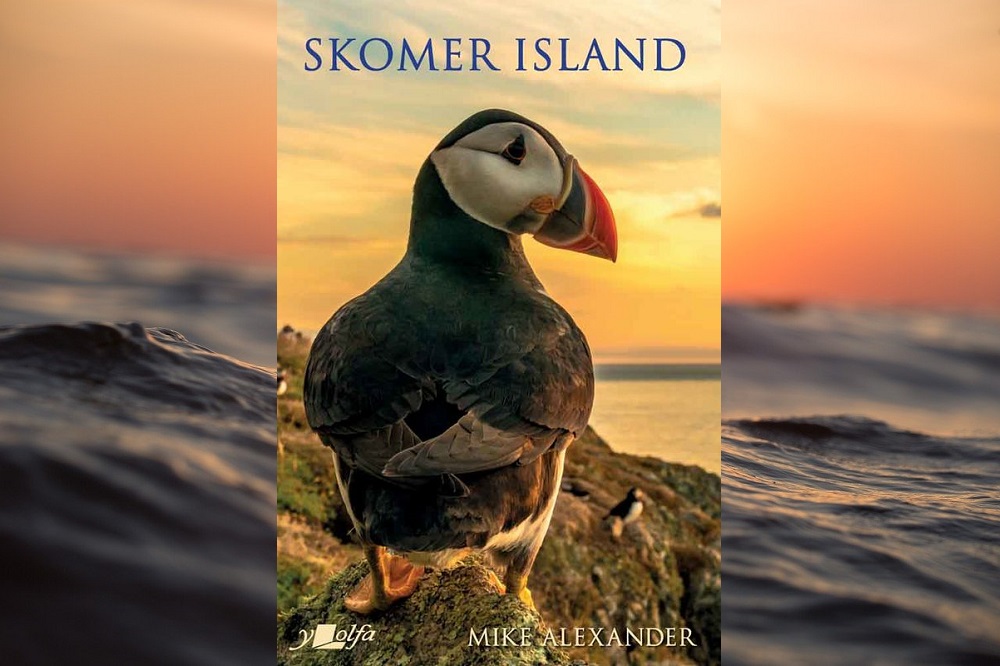

Skomer is one of the best of our nature reserves, where thousands of visitors enjoy the spectacle of its busy seabird colonies, especially the puffins which are emblematic of the place and dutifully adorn the volume’s cover. But although the day visitor will see these and other seabirds such as guillemots, razorbills and a selection of gulls there are some birds which only land here at night. One of these is the Manx shearwater, a small albatross-like bird which nests in burrows which it visits after long fishing trips out into the Irish Sea. Just before they make landfall they congregate in great rafts which Alexander elegantly describes from the perspective of an open boat drifting among them:

“There was a heavy but lazy swell: rolling hills of shiny grey water. Soon, perhaps a mile offshore, we began to see an occasional Shearwater. Then suddenly, we were surrounded by a huge flock of birds, wheeling past us on both sides of the boat, flashing black and white as they turned, constantly changing direction as they navigated through the hilly waves.”

Spiritual home

Mike Alexander first visited this island – which is home to a third of the world’s population of Manx shearwaters – when he was a 13 year old, a day’s school trip which ended with the young man deciding he would someday be the island’s warden. In 1976 he realised that ambition and then spent what he describes as the best ten years of his life there, in what will always be his ‘spiritual home.’

The research that has gone into this book is staggering, although the author wears his learning well as he presents a small, fecund world, 3kms long, surrounded on all sides by the sea in prose that is unfussy and clear, turning stacks of scientific reports and studies into accessible accounts. So we encounter the unique Skomer vole, so tame it will settle unworriedly in a person’s palm, or thrill at the spectacle of thousands of young guillemots taking their first plunge into the sea together.

It is a book that tells of the human history as well, from the prehistoric farmers lived in hut circles to the last of its farmers. They include colourful characters such as Vaughan Palmer Davies, a former captain of an ocean-going brig who followed thirteen years at sea engaged in the opium trade with thirty years farming and shooting on Skomer. There was also Reuben Codd, who was one of the many islanders who found a source of income in harvesting rabbits and of course, Ronald Lockley, the sometimes irascible author who enchanted Alexander with his accounts of island life just as he did many thousands of delighted readers.

The island has attracted many notable naturalists over the years and one of them, Robert Drane wrote entertainingly in the Transactions of the Cardiff Naturalists Society about the tail end of a night out among the shearwaters on an island he only refers to as Golgotha, perhaps a reference to the birds skulls which litter the ground on Skomer.

“Who’s that calling? – it was the Oystercatcher, the warder of the east, who cries ‘The dawn! the dawn! The next to wake are the gulls, the Puffins next, and we go home about 3.15, knee deep in bracken, drenched with dew. We then had some whisky and water. I drank the whisky and Mr Neale had his dew. I went to bed feeling I had seen the world of the shades, and when I come to stand by the dark river’s side I shall feel that I have been somewhere thereabouts before.”

The book is crammed full of fascinating facts, such the Irish name for the aforementioned Oystercatcher is Giolla Brighde, which means ‘Servant of St Brigit’ a saint whose name became San Ffraid in Welsh and St Bride is English and of course Skomer is to be found at the southwestern tip of St Bride’s Bay.

Henry VIII

We learn about the longest seal journey, when a tagged male from Pembrokeshire in September 1960 was found in Santona, Spain just three months later and how the rents from the islands were gifted by Henry VIII to Anne Boleyn just a few years before she was beheaded in 1536.

The text is complemented by a wealth of photographs by the author, some revealing scientific images which show such things as the changes in the vegetation as well as a fine trawl of family history snaps, which document domestic life on the island before it became a National Nature Reserve, so we have turkey-feeding and cows being miked in the open air, and of water being collected by servants from the well in a wooden pail.

But it’s the wildlife which will draw readers to this fine, compendious and, well loving account of this jewel in the Welsh wildlife crown. It’s a book to get lost in, one that takes the armchair reader into her or his own memories of this sea-girt isle, with its chattering ranks of seabirds and if one is lucky the sight of a day-flying short-eared owl quartering over the island, its long wings flapping like a big moth. Or a close encounter with a puffin. Or a razorbill, often overlooked because of its comical cousin and yet the symbol of the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park.

This is a splendid book to grace the shelves of anyone with an interest in natural history and a meaningful souvenir for anyone who has been to Skomer and marvelled – in the fullest meaning of the word – at its wildlife wealth, which can give the spectacle of African game more than a run for its money.

Skomer Island is published by Y Lolfa and can be purchased here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.