Review: The Covenant reminds us how recently we have come to expect a long life

Sarah Tanburn

Cwmderwen is one of those narrow, steep-sided valleys rich in stones and scrub. The Owen family are proud tenants of twenty-four acres, one rood and eight perches. Led by patriarch Thomas, they work hard on the small farm in the week and pray hard in chapel on a Sunday. Near the start of the book, a blazing rainbow confirms their conviction that the land is theirs by divine right.

Leah, youngest and brightest daughter sees her beloved preacher become a missionary in China. She is resigned to the limits imposed by her sex, but dreams of becoming a teacher. Tragedy strikes the family, though, and everything changes. Leah, not seeing the risk, is caught at home as the unmarried girl kept behind to look after her parents. Silent and determined, she takes up the reins of the farm; it is Owen land, she fervently believes, and she will hold it for the next generation, come what may. Leah is almost daunting in her resilience and her apparent ability to rise to every challenge. Moore keeps her fallible enough to keep our attention, as allies and enemies swirl around her.

Covenant is the prequel to Moore’s first novel A Time for Silence. I must confess, I haven’t read that yet, but here’s the good news: you can enjoy this one all on its own.

As you would expect from the title, this novel explores many promises, spoken and unspoken. The vows exchanged or withheld between men and women, long-nurtured commitments to revenge and many others drive the plot.

This is also very much a story of death. For this community, death in infancy is so common that the children are barely remembered by any but their grieving mothers. Harder to swallow are the deaths of teenagers and youngsters. Long before the engulfing slaughter of the 1914-1918 war, the families of Cwmderwen lose loved ones to injury and illness. Some of these deaths are forgiven, but some are not.

Reading it now, as the country endures so much death which could have been avoided and we brace ourselves for more, Moore’s work reminds us how recently we have come to expect a long life for most of us. Covenant’s tales of mistreated wounds, undiagnosed disease and unaffordable medicine are a grim memory of times still (just) within living memory.

Curse

Of course, alongside death and promises, there is sex. In this enclosed, religious world, sex is everywhere. Even the most gentrified of ladies knows that sheep must breed and lambs cared for. The upright deacons of the chapel condemn lasciviousness, gambling and drink, but it doesn’t stop the reality tumbling in the streets of the local market town and seducing the youngsters away from righteousness.

In another sense, too, sex is of overwhelming importance. Leah would inherit the tenancy from her father if she was a son, but as a mere girl he dismisses any such option. Her brother must instead take on work he hates. This curse extends to the next generation, as young Annie flees her home into service to escape a worse fate. We have, thankfully, travelled some way from that predetermination, at least in this part of the world, and Covenant reminds us how precious, and maybe fragile, those changes are.

Equally changed is the religiosity of Wales. The novel is set during a wave of religious revivals; the fervour of seeing the light is itself mirrored in the passions of the family, even as loss of faith is crucial in their fortunes. Today that overwhelming importance can be hard to reimagine as Wales has become one of the least observant countries in Europe. (By some way, Wales now has more people declaring ‘no religion’ than any other UK nation, according to the Office for National Statistics.)

I grew up in a religious household, albeit in which one where the tambourine was as important as the organ, so I recognise some of Leah’s pain in doing her duty, the importance of the bible in their daily lives, and the hierarchy of deity, land and family. Moore draws this out beautifully, an education for anyone wondering why and how faith has shaped this land.

Stubborn

In all this change – of mortality, conduct and expectation – the landscape remains the same. The valley of the Owen farm is fictional, but any explorer of the Welsh countryside has been there. If you walk in the hills, you will know the steep sides and scrubby trees, the sudden explosions of rain or the mizzle drifting across the slopes. You have seen the intensity of green which fills the eyes till they brim at the beauty of it all.

And of course, the noise of wind and falling water which accompanies you everywhere. Moore gives us this hard-working, stubborn landscape as itself the character of the family and community. Without them, the land would be different, but they could not be who they are without the land on which they live.

Enjoy Covenant. In the meantime, I am adding A Time for Silence to be my ‘to be read’ pile, as I’d like to know what happened next.

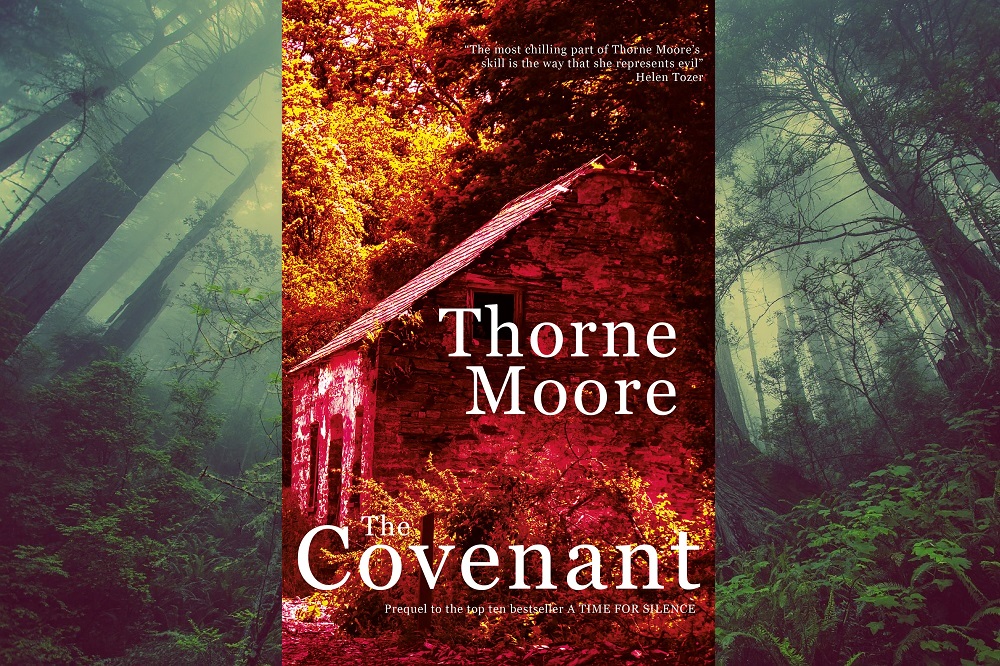

The Covenant by Thorne Moore is published by Honno and can be bought here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.