Review: Welsh Saints from Welsh Churches by Martin Crampin

Nathan Munday

In Philip Larkin’s poem ‘Church Going’, the sardonic speaker steps into what Nietzsche may have termed a ‘tomb’ or a ‘monument of God’. Hatless, he removes his ‘cycle-clips’ before being drawn further into the ‘special shell’ of an English church. In the third stanza, he wonders why it is that he still gravitates, like so many artists, to these religious sites…

In Wales, our llans were never fully secularised. Churches may have closed, and chapel pews border so many of our dining rooms, but the names that follow each llan stubbornly remain.

We’re intrigued by these coracle saints and leek-eating hermits that prayed their way around our coasts; these were genuine believers that left their lug worm traces in the land. Along with their wells and cells, we find ourselves irresistibly drawn to their tales and depictions. See Benjamin Myers’ latest novel, Cuddy.

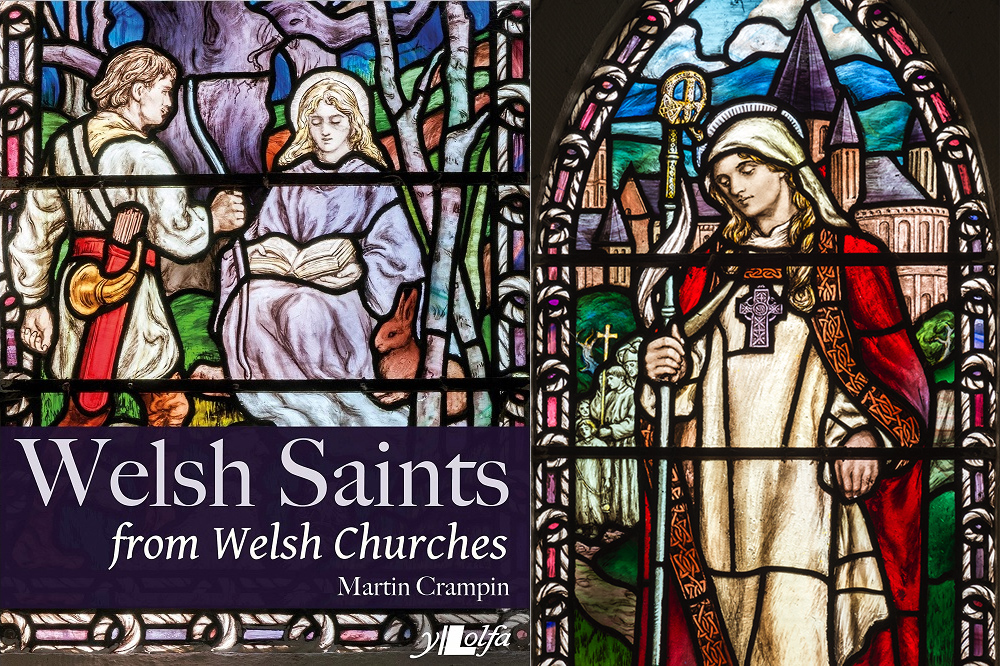

Perhaps the time has come for us to re-acquaint ourselves with these characters. Martin Crampin’s Welsh Saints from Welsh Churches is the best place to begin. His expert eye captures these curious figures, curating their depictions in a work that sits comfortably on any coffee table or on a scholar’s desk.

Photo by Martin Crampin

‘I Step Inside’

The book is exquisite. Its images illuminate the pages in a medieval way, allowing us to scan the beauty of holiness and appreciate the skill of the stained-glass artists throughout the ages.

On the front cover, an image of San Melangell – that saint who hid the hares – sits with downward eyes, deep in Scripture, unaware of the archer’s threat.

In the middle of the book, Dewi Sant metamorphoses from an ornately dressed abbot, into a Celtic seer, then a Cadfael lookalike, before turning into a kneeling Christ-like figure receiving instruction from an angel with red wings!

Each page gives us similar glimpses into forgotten stories that adorn the ivy-covered places which are now ‘let’ ‘rent free to rain and sheep’.

The Creation of the Past

As an artist and photographer, Crampin’s interest transcends the quirky hagiographical detail. In the preface, he writes:

I first became interested in the Lives of Welsh saints as examples of medieval narratives arising from oral tradition while writing about the creation of the past in medieval Welsh prose tales, and the interactions between these narratives and landscape. I subsequently made two sets of images concerning the saints Gwynllyw and Tatheus (Tathan) from 1999 to 2001, with the aim of making these saints better known in the places they were venerated.

His own journey as an artist saw him incorporating architecture, landscape, projection, audio clips, and archaeological remains into his work. A process, he tells us, that sought to convey ‘the transition from amorphous oral tradition into a fixed literary form as written hagiography’.

During his periods of extensive research, Crampin encountered the stained-glass windows which form an unlikely quarry for our nation’s story. He records the makers as well as the saints.

In so doing, he produces a robust study which functions as a chronicle of Welsh spirituality. How these saints appear is as important as who is depicted.

Dorian Llywelyn in his Sacred Place, Chosen People: Land and National Identity in Welsh Spirituality explains that:

Place as a concept is far more than a material description of territory, since it involves relationship with the divine, with particular societies and with individuals, all of whom have a temporal, intrahistorical aspect […] Place and identity – individual, communal and national – relate to each other intimately, and any attempt to describe an ethnic Welsh spirituality must include both.

What Llywelyn is referring to here is the whole concept of Wales; he argues, convincingly, that the construction of its territory, landscape, nationhood, people, and aesthetics is infused with theology.

Crampin sensitively surveys this charged landscape, gathering the saints that stare down at us from holy walls, who linger on road signs, or are mispronounced by that robot on Google Maps.

‘So many dead lie round’

Forty four saints are discussed in detail in the second half of the book. Famous names like Dewi, Teilo and Deiniol are included; others like Seiriol and Cenydd are also introduced.

Before zooming-in on these individuals, Crampin provides a fascinating study in the form of three sections. The first asks ‘Who were the Saints of Wales?’

I was fascinated by the conflicting claims, chronologies and traditions which halo these figures. Furthermore, he reveals how depictions of our saints travelled as far as their original subjects.

Photo: Martin Crampin

Crampin then considers ‘The Imagery of Welsh Saints’, tracing the evolution from sculpture and wall-painting to the glasswork which later dominated.

Well-established European iconography helps us identify many without the need for inscription. For example, St Catherine’s wheel is known to us since it rolls its reincarnation on our November nights.

Peter’s keys is another easy one as are Melangell and her hares, but it can be tricky to identify the ‘so many dead’ that ‘lie round’.

Finally, the author discusses the process of ‘Visualising the Saints and their Iconography’ which ultimately lies in the realm of imagination. Historical accuracy was rarely an important consideration:

The survival and proliferation of these stories has a long history and can reveal much about the storytellers and writers that created them, and the local and ecclesiastical communities that chose to preserve and embellish these traditions. The imagery of Welsh saints also belongs to the periods in which it was created, and cannot accurately reflect the period when the saints were presumed to have lived.

Illumination

These images and stories have become embedded in the fabric of Cymru. I imagine the author pilgriming to many secluded spots and spending hours in his scriptorium.

I imagine him meticulously compiling his work with the devotion of those who illuminated vellum or sourced that precious blue soda.

This treasury of a book reminds us that our story is a very old one, and that church going is in fact illuminating and not that boring at all.

Welsh Saints from Welsh Churches by Martin Crampin is published by Y Lolfa. You can buy a copy at all good bookshops.

You can also learn a bit more about the author here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.