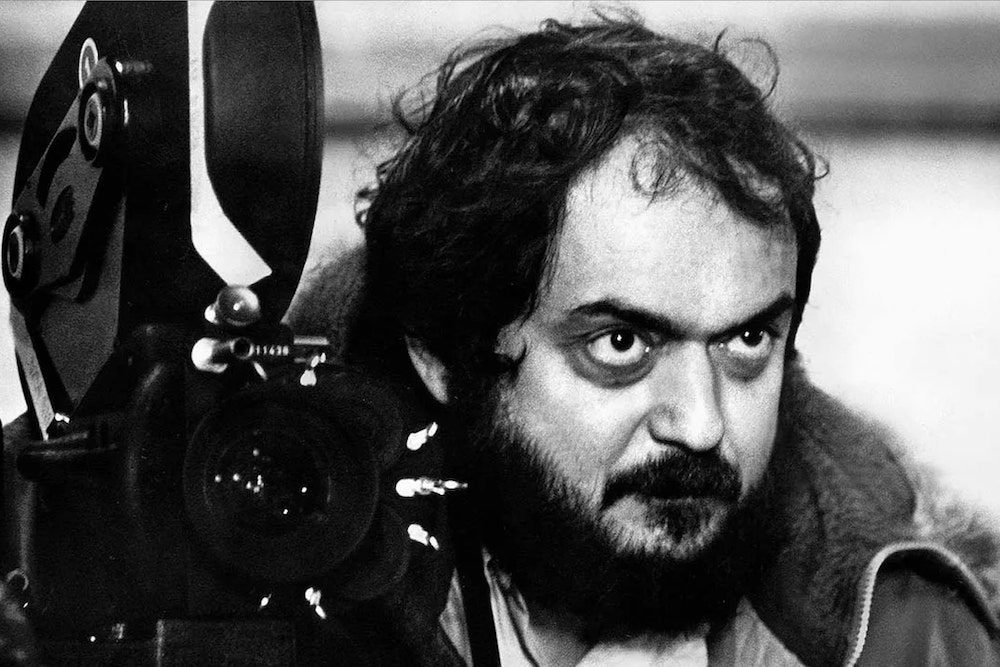

The secret Welsh history of Stanley Kubrick

Nathan Abrams

The legendary director Stanley Kubrick who died 25 years ago this month was not Welsh. Neither did he, as far as we know, visit Wales but there are many interesting connections between him and our country – some strong and some tenuous.

Anticommunism and Cymru

Kubrick’s connections with the UK began in the early sixties when he relocated there to shoot his controversial pic Lolita, an adaption of Vladimir’s novel of the same name. But his links with Wales only began with his next film, the black comedy Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb which was released in 1964.

He adapted that film from the novel Two Hours to Doom by Welsh writer, Peter George, which had been published in the UK in 1958 as Two Hours to Doom under the pen name Peter Bryant and in the US as Red Alert the following year.

Born in 1924 in Treorchy, Rhondda, George was the son of a Welsh schoolmaster and had served in the RAF during World War II, flying night missions, before being called up for the Korean War, after which he remained in the service, taking a commission until 1961 when he resigned to write full-time.

His novel narrates how a US general becomes depressed after being diagnosed with a fatal illness and launches an unauthorised pre-emptive nuclear strike on the Soviet Union when he orders his B-52 bombers to attack targets inside the country. The commander seals his base, knowing that the military will soon arrive to try to discover the recall code that only he knows. Cooperation between the Cold War powers narrowly prevents disaster. It became a bestseller and was serialised in the Saturday Evening Post and was chosen as a Book-of-the-Month Club selection.

Kubrick and George worked closely together on adapting the novel. In November 1961, Kubrick introduced himself in a modest, three-page letter outlining his background as a filmmaker and his admiration for Red Alert. He asked George to work with him in adapting his book into a screenplay. Early in the new year, George travelled to New York to begin working on the script. The director and writer could not have been more different. Where Kubrick loved cigarettes and coffee, George was morose and a heavy drinker, ‘absolutely awash with liquor’, according to Kubrick’s widow, Christiane. Nevertheless, the pair worked well together and George ultimately received a co-screenwriter credit.

In the film, US General Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden) describes the fluoridation of tap water as “the most monstrously conceived and dangerous Communist plot” the West has ever had to face. Kubrick possibly got this idea from the reports into the first experimental fluoridation scheme in part of Anglesey in the mid-1950s. He noted that the UK Ministry of Health had carried out a Fluoridation study there in 1955 and some of this report makes it into the draft script.

The Dawn of Man

It was really Kubrick’s next film that drew upon Wales and Welsh creativity and mythology. Although born in London, Ivor Powell’s name suggests a Welsh heritage and he stood in for the actor who played Kaminsky inside the Hibernaculum. They needed someone who could keep their eyes closed without their eyelids ‘flickering’ which wasn’t easy under ‘close scrutiny’. Annie Walker, a Welshwoman from Cardiganshire drew the director when she was working as an artist on the film. Her job was to create some of those realistic-looking models that were required in the pre-CGI era.

The source for the film was one of science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke’s short stories, ‘The Sentinel’, published in 1954. In the story, the narrator refers to ‘the old Welsh air, “David of the White Rock”’. Known in Welsh as Dafydd y Garreg Wen, this traditional folk song was said to have been composed by harpist and composer David Owen (1712–1741) who lived near Porthmadog.

Although the white rock became the black monolith in the movie, the name David remained in the lead astronaut, Dr. David Bowman. And his family name certainly suggests a harpist, or perhaps a Welsh archer at the battle of Agincourt. David is, of course, a popular name in Wales. In July 1967, one year before the film was released, Kubrick wrote to Clarke. ‘Did you see the fantastic item in TIME’s science section (21 July) about the discovery in a Welsh urinal that throws light on the existence of life on Jupiter?! Can we work that into the script?’ I do not know what was found in a Welsh toilet in 1967 that pointed to extra-terrestrial life in Jupiter but it would certainly be fascinating to know how it influenced the film.

When scouting for locations for the Dawn of Man sequence that opens his magisterial 2001: A Space Odyssey, Andrew Birkin (brother of Jane) was tasked by Kubrick to scour the British Isles for a desert-like landscape. Eventually, he located Parys Mountain, an abandoned eighteenth-century copper mine on Anglesey.

It provided a ‘spectacularly ravaged golden-orange landscape of serrated buttes and rockfalls’, wrote one observer. Birkin also came across the sand dunes of Newborough Warren – also on Anglesey — which, if shot correctly, was framed by the mountains in the distance. Kubrick was particularly taken with this idea and sent his production designer Tony Masters to take a look at it. By this point in the production, though, autumn was approaching and anyone who knows Wales knows well that attempting to recreate a sun-drenched African savannah in September was an impossible ask. Ultimately, he shot the scene in Namibia. Birkin, though, liked the area so much that he moved to just outside Pwllheli.

Leonard Rossiter, who played Soviet rocket scientist and astronaut Dr. Andrei Smyslov, was evacuated to Bangor in North Wales during the Second World War and stayed for about 18 months. (In the film, the segment following the one he appears in, takes place 18 months later…) He meets Dr. Heywood Floyd whose last name, apparently, is an English variant of Lloyd, originating from the Welsh name Llwyd (meaning grey or grey-haired).

Much ink has been spilt on the origins of the name of the supercomputer, HAL, but none have considered its Welsh meanings. I found six definitions for hâl in the dictionary: salt, filth, moor, hall, strong and the act of parturition. Certainly, the final two fit the computer who murders all but one of the crew and hence (unwittingly) gives birth to the next stage of human evolution. One of those murdered by HAL is Dr. Jack Kimball. According to Wikipedia, Kimball is Old Welsh for ‘war chief’ and Old Celtic for ‘leader of men’.

On the subject of Welsh names, it is curious that one of four key characters in Kubrick’s next film, A Clockwork Orange (1971) was called Dim. Leonard Rossiter popped up again in Kubrick’s following film, Barry Lyndon (1975), as a prim and proper English Army officer.

For this costume epic, the entire cast and crew travelled by train and then ferry to the Republic of Ireland. Most likely they passed through Bangor on their journey to Holyhead but we have no evidence that he alighted the train (even to use the bathroom).

Before that had happened, Kubrick had his production designer, Ken Adam, scout for locations in the Republic and the UK. Some of those considered were the Begwyns Mountains near Hay-on-Wye, Blaen Cwm Claisfer above Llangynior, Tregoyd and Velindre above Llanigon near Hay, a track off the A40 at Llansantffraed in Monmouthshire, Gilwern Hill above Abergavenny, Tor y Foel mountain above Talybont in Brecon, and Carreg Waun-Llech above Llangattock. Ultimately, none of them were used.

Thereafter the connections become more tenuous. In The Shining, there is a ghostly barman called Lloyd whose name means grey in Welsh. The boy who plays Danny Torrance is similarly called Danny Lloyd. A purple corduroy dress with purple buttons that ran up the front to the collar that Shelley Duvall as Wendy Torrance wore in the film was made in Wales.

The Vietnam War film, Full Metal Jacket, which Kubrick released in 1987 was heavily influenced by the work of photojournalist Philip Jones Griffiths. Born in Rhuddlan, his 1971 book Vietnam Inc. became a key source for Kubrick’s imagery. He even cut eighty-five pages out of the book for reference.

In 1991, Kubrick’s sword and sandals epic, Spartacus, was restored. This gave Kubrick the chance to reclaim his cut of the movie that had been bowdlerized by the studio when initially released in 1960 which was one of the reasons Kubrick abandoned Hollywood and Los Angeles. The legendary ‘snails and oysters’ scene, in which Crassus attempts to seduce his ‘body slave’ Antoninus, had been cut from the original release.

It presented a particular problem as it had to be reconstructed but Laurence Olivier, who played Crassus, was dead. His widow, Joan Plowright, recommended Anthony Hopkins, whose impressions of the great actor used to drive him crazy. Hopkins agreed to help and dubbed Crassus’s dialogue, directed by Kubrick via fax.

Among the preproduction research materials for Kubrick’s final film, Eyes Wide Shut were pictures of the druidical robes worn during the Eisteddfodau. While making that film, Kubrick was given the Directors Guild of America’s highest honour, the D.W. Griffith Award, recognising his lifetime contribution to cinema. Griffith had been born in 1875 to Welsh parents in Kentucky. In his acceptance speech, Kubrick explained the appropriateness of naming the award after Griffith, whose career was marked by both cinematic and financial success as well as a sudden downward turn.

He was always ready to fly too high. And in the end, the wings of fortune proved for him, like those of Icarus, to be made of nothing more substantial than wax and feathers, and like Icarus, when he flew too close to the sun, they melted. And the man whose fame exceeded the most illustrious film-makers of today spent the last seventeen years of his life shunned by the film industry he had created. I’ve compared Griffith’s career to the Icarus myth, but at the same time I’ve never been certain whether the moral of the Icarus story should only be, as is generally accepted, ‘Don’t try to fly too high,’ or whether it might also be thought of as, ‘Forget the wax and feathers and do a better job on the wings . . .’

Nathan Abrams is a Professor of Film at Bangor University and the co-author of Kubrick: An Odyssey which can be ordered HERE

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

So, none then.

I learnt a few things there, Thanks Prof…

A few copies of Red Alert about, not cheap…

Great article. Very interesting reading. It seems Wales and Welsh mythology has influenced many of note but rarely gets a mention or the credit deserved. And yes, some connections can be construed as tenuous, but most are because Wales played its part in historical For example. The real life James Bond came from Wales , in particular , Pontypridd via Swansea , who became Ian Flemming’s world famous secret agent. His name was James Charles Bond. He served under Ian Flemming as a Special Operations Executive (SOE) during WW2, and although Flemming stated that his character was named after an… Read more »