The weird Shakespeare illustrations of forgotten Welsh Victorian illustrator

Michael John Goodman

Kenny Meadows would often hold his hand up, point at it, and declare, ‘I cannot see a hand as I would draw it’.

Meadows, who was born in Cardigan, Wales, in 1790 – and according to contemporaries, spent his younger years living in a lighthouse – might just be the strangest Illustrator from the Victorian period you have never heard of. The illustrator disdained drawing from ‘nature’, preferring to use his imagination and flights of fancy.

A self-taught artist, Joseph Kenny Meadows (he would drop the Joseph part of his name), lacked any formal training and was simply not interested in creating art that did not showcase his own inventiveness and creativity.

Described in the period as being a ‘clever, erratic genius’, an illustrator who ‘did as much for illustrative art, as perhaps any artist, for the time’, ‘a witty man’, and a ‘sad Bohemian, a jovial soul, loving company and the refreshments that attend it’, Meadows was a ‘considerable celebrity’ who included in his friendship group such writers as Charles Dickens and William Thackeray. Indeed, as one Victorian writer wrote, ‘Few men of his day enjoyed so great a vogue as Kenny Meadows’.

There are no records of the first several decades of Meadows’s life and the first time his name appears in print is in 1823 for some lithographed plates he designed for King Lear. However, Meadows’s first major work that brought him to the attention of the public was a project entitled The Heads of the People: Or, Portraits of the English, published in parts between 1838-40 and then in book form that same year.

The work saw Meadows illustrating archetypical English caricatures in their different social or professional roles, such as ‘The Chimney Sweep’, ‘The Housekeeper’, and ‘The Young Lord’. A series of writers would then write essays to accompany them. The illustrations are instantly distinctive, playful and imaginative and it is easy to understand why the publication was hugely popular.

The success meant a second volume was produced the following year. But it is Meadows’s next project that brought him acclaim from his contemporaries and why Meadows remains such a unique and fascinating illustrator today. Between 1839 and 1843 Meadows produced over one thousand illustrations for Robert Tyas’s ‘Illustrated Shakspere’ (In the early Victorian period writers would sometimes spell Shakespeare this way as they felt this was more authentic to how the playwright actually spelt his name).

Tyas had been the publisher of The Heads of the People, and he was evidently wanting to repeat that success by capitalising on the Victorian’s love of all things Shakespeare as well as recent developments in printing techniques that meant images and words could be combined on the same page cheaply and effectively.

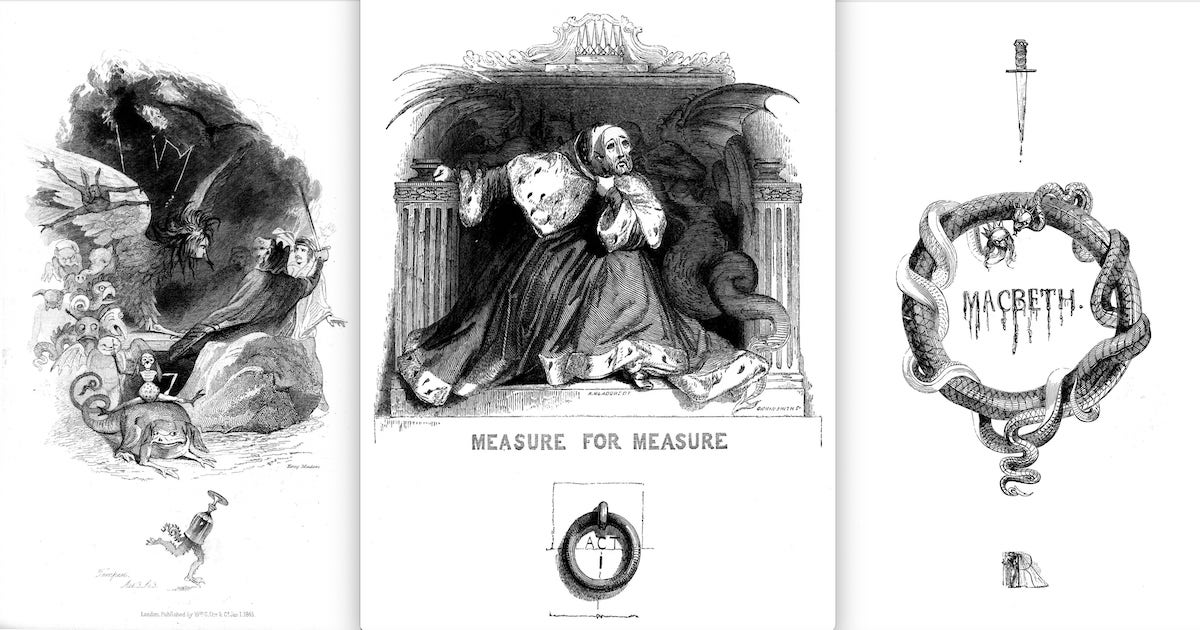

The result is an incredible visual experience in book form. It is a masterpiece of design, where Shakespeare’s characters are frequently transformed into animals, where symbolic cherubs are used to comment on aspects of the plays, and where visual motifs like flowers, discarded clothes, or broken swords are used to signify the end of a scene or act. When characters haven’t been turned into animals, they are often presented as gothic and grotesque exaggerations of themselves. All of this while both the publisher and Meadows innovatively exploit the new opportunities the technique of wood-engraving presented to them to creatively play with the relationship of word and image on the page.

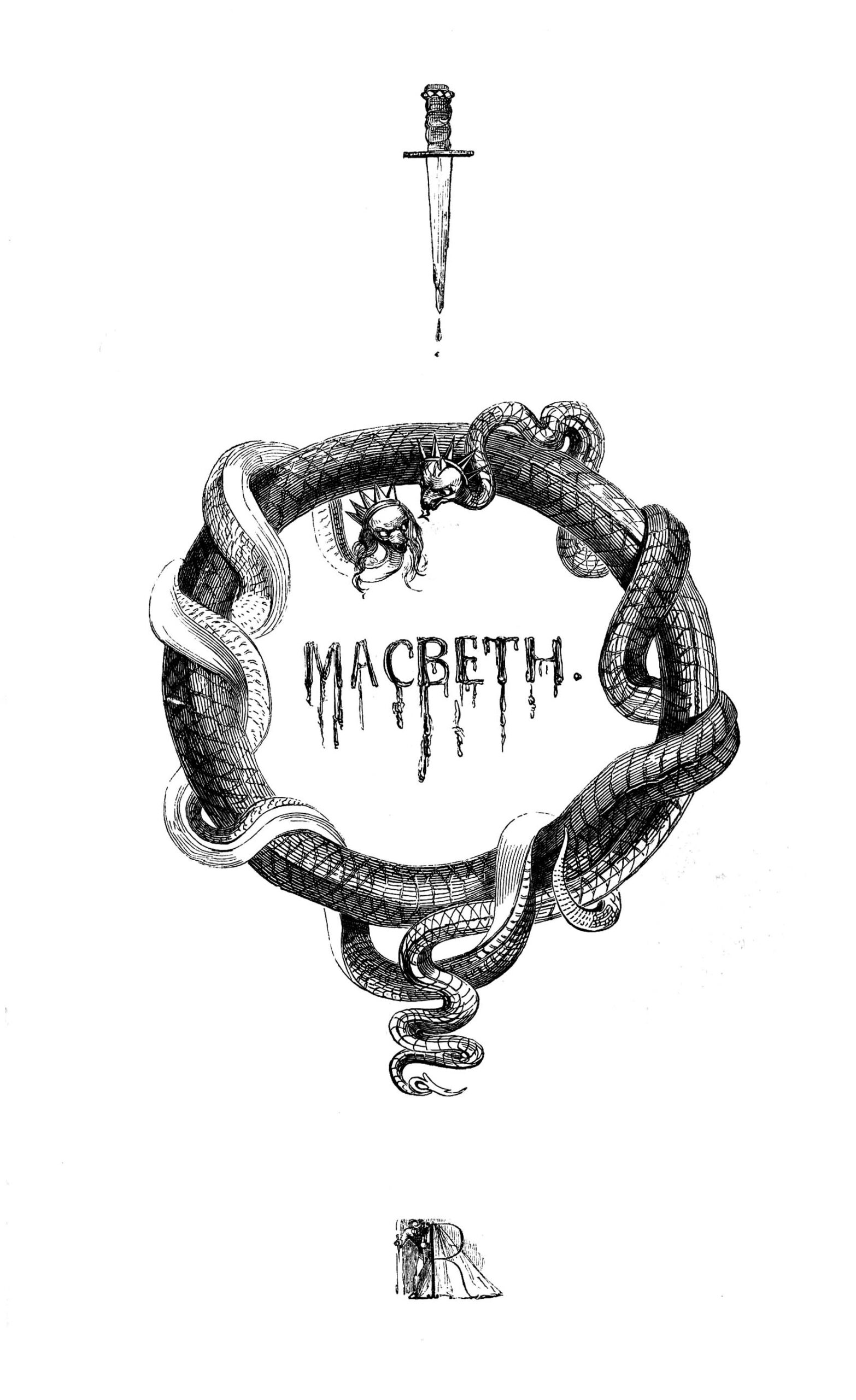

The title page of Macbeth, for example, presents both Macbeth and Lady Macbeth as snakes wearing spiky crowns, wrapped around each other in a circle, their destiny completely entwinned, while a dagger hangs above them, dripping blood. In the centre of the circle formed by the snakes the lettering of ‘Macbeth’ is also presented with blood dripping from each letter.

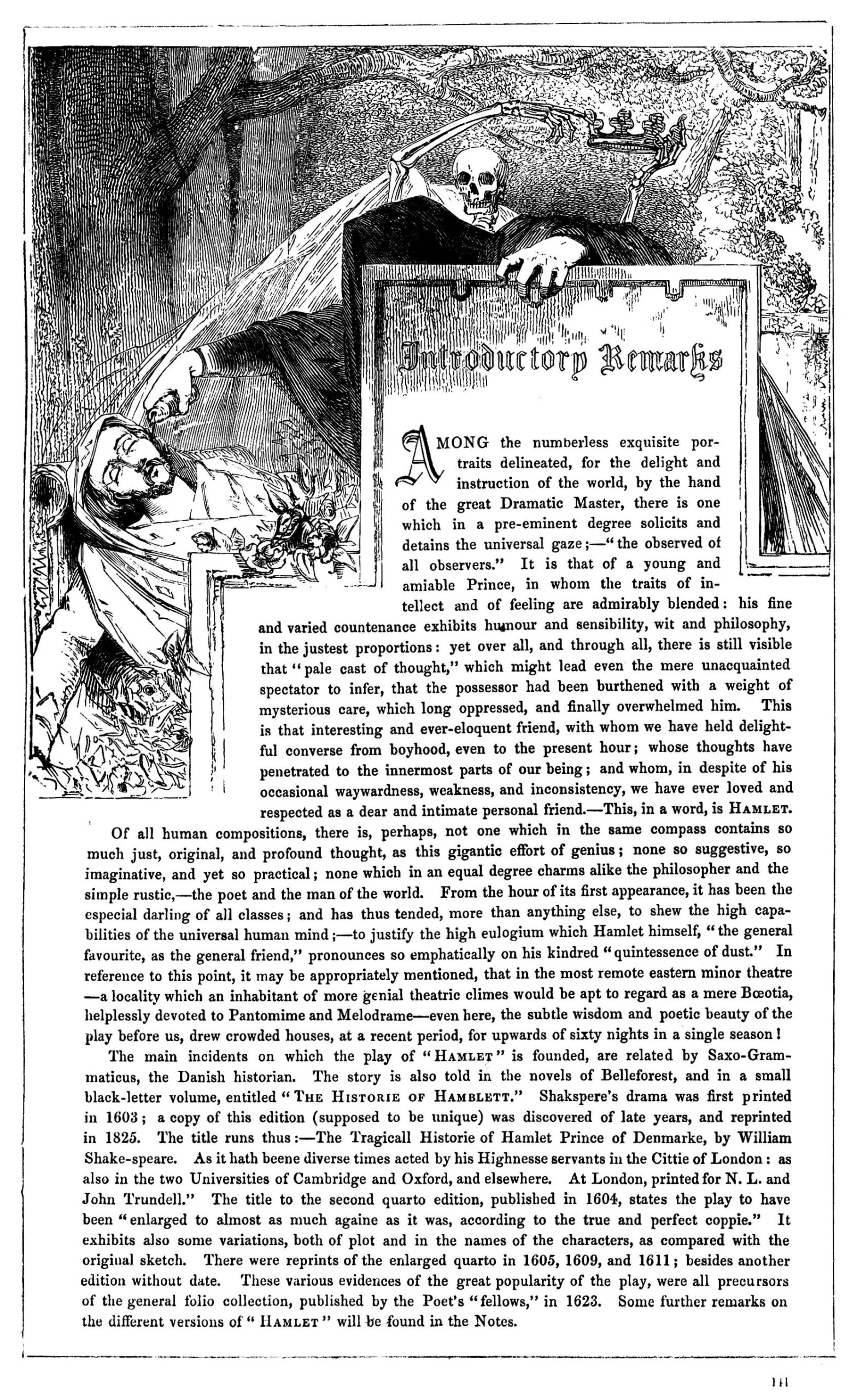

Another remarkable illustration is on the ‘Introductory Remarks’ page of Hamlet, where a skeleton is depicted as standing behind a shrouded Claudius as he pours poison into his brother’s ear. The skeleton looks on with pleasure as he grabs the crown. Meadows uses the page imaginatively so that the aforementioned ‘Introductory Remarks’ are written on a grave that Claudius is on holding on to, using the full scope of the page to express his creativity.

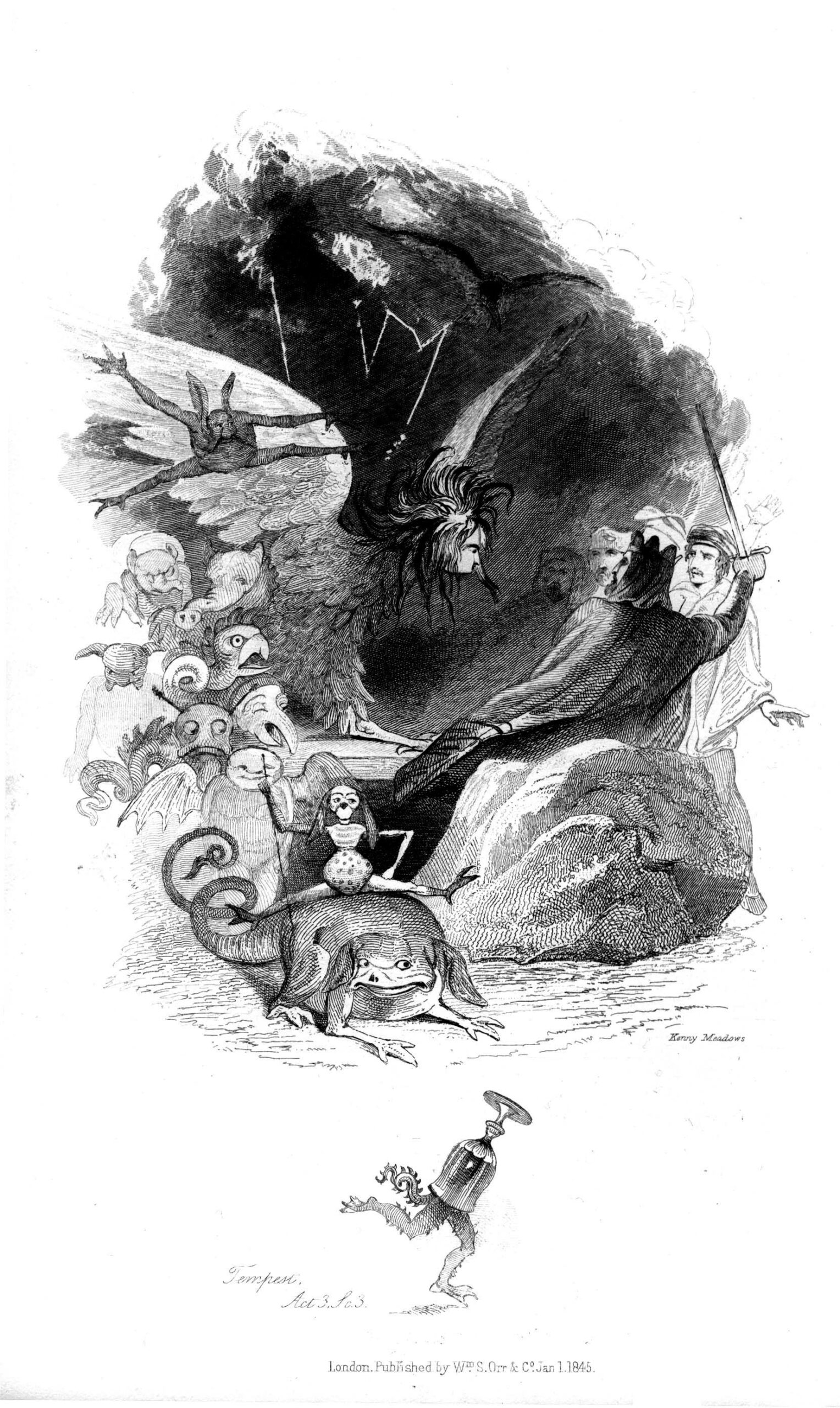

Perhaps one of the oddest illustrations is the frontispiece for The Tempest which depicts the scene from the play where Ariel appears to Alonso and the other Neapolitans, whilst ‘strange shapes’ also appear to take away the banquet. Meadows portrays the ‘strange shapes’ as very odd, weird, looking creatures – unlike anything how this scene had been depicted before or since. One of the creatures sits on top of a strange lizard holding a staff, while another one, in a comical piece of inventiveness, is seen running off with a wine glass on its head. This juxtaposition of the peculiar and unnerving with the comical is at the heart of Meadow’s work.

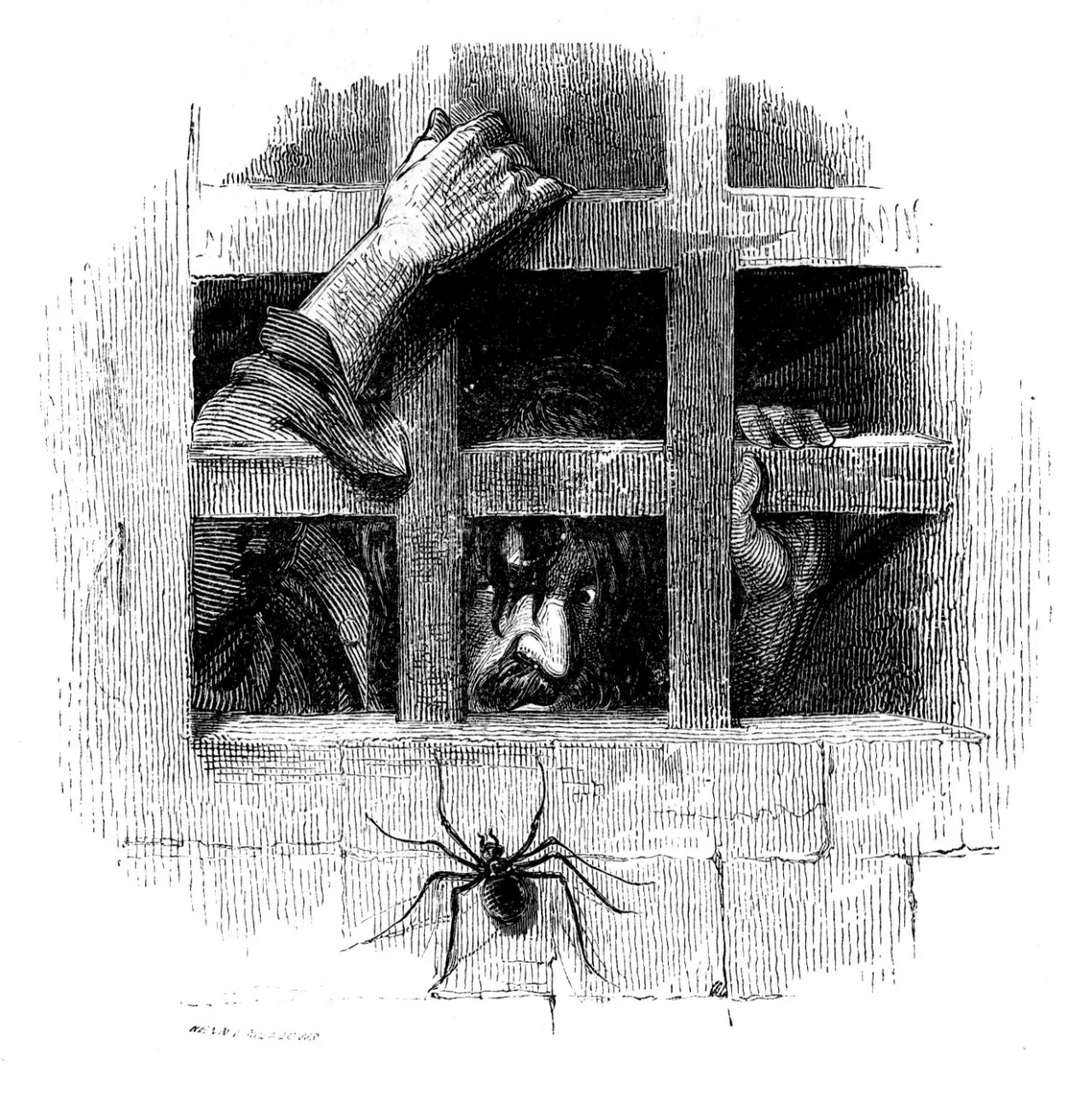

A couple of final examples, taken from Measure for Measure, to emphasise how unique Meadow’s work is: The first is the Act I Headpiece which presents the Duke, looking out deviously from behind a mask, while dark winged shapes surround him in the background. It is a disturbing image for a problematic play. The final example is Meadows’s portrayal of Barnadine, who is in his prison cell, but looks out from behind his bars in dread at his predicament, as a large spider crawls up the cell wall on the outside. There are countless images like these in the ‘Illustrated Shakspere’

The publication was a big success and the ‘Illustrated Shakspere’ would be reprinted many times throughout the Victorian period. A contemporary review of the edition in the London Courier declared: ‘Kenny Meadows has most certainly –– and it is a great thing to say but a truth nevertheless –– proved himself to be the most accomplished and successful artist who ever assayed the ambitious task of realising, by the pencil, the conceptions of the greatest of the greatest of our poets’.

Meadows would go on to work for the periodicals Punch and the Illustrated London News. While he illustrated many other books during his lifetime, he would always be remembered for his illustrated edition of Shakespeare’s plays, and in 1864 he was awarded a government pension by the Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, ‘in consideration of the merit displayed in his Illustrated Shakespeare’. He died in Chelsea in 1874, aged 84 – a substantial age for the time.

If anyone is interested in exploring Kenny Meadows’s illustrations to the ‘Illustrated Shakspere’, they can view them all here, on my website, the Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive (www.shakespeareillustration.org).

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.