The Welsh rooftop gig by the band that would become Underworld

David Owens

Anyone who has watched Peter Jackson’s epic documentary series ‘Get Back about the making of The Beatles’ 1970 album ‘Let It Be’, will know it culminates in John, Paul, George and Ringo playing their fabled rooftop concert.

That gig up on the roof of the band’s Apple Records’ building on January 30, 1969 has long passed into folklore – another remarkable chapter in the life of a rock ‘n’ roll group that defined the ‘60s.

Some bands such as The Fab Four explode like a supernova. others take far longer to take their place in the rock constellation.

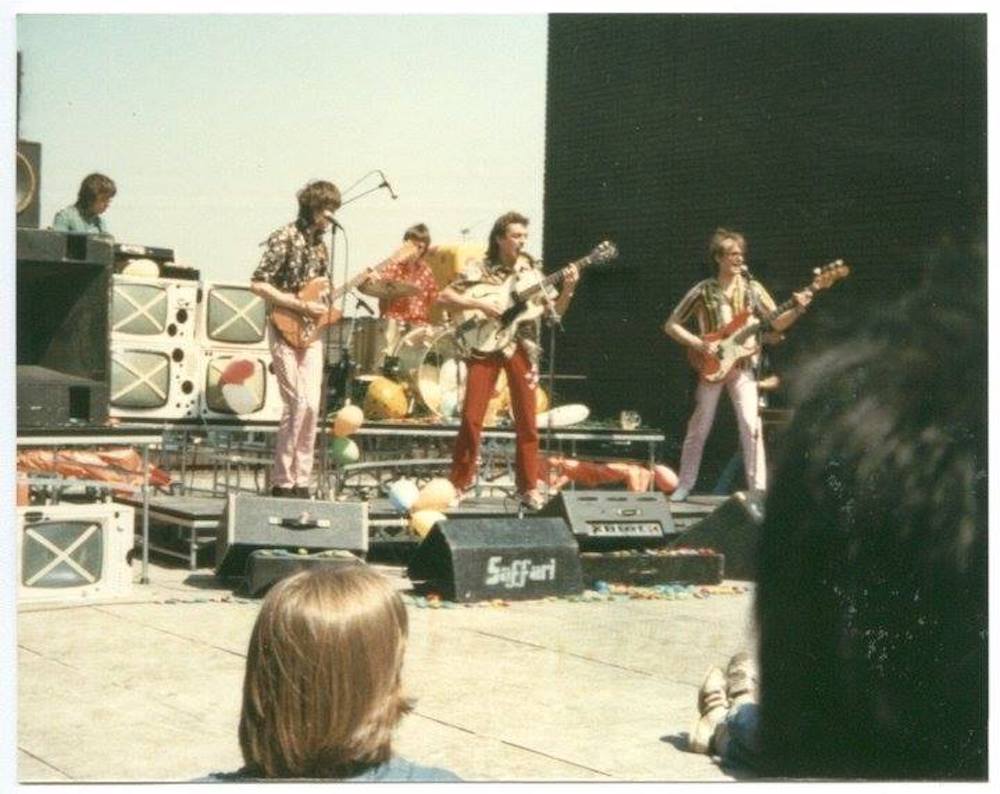

Fast forward 11 years to May, 1980 and there, on a roof of Cardiff University students union, was another band with stars in their eyes and dreams of scaling similarly stratospheric heights.

Their incubation would be a lot longer. A 15 year overnight success story. However their seismic effect would be no less dramatic when injected in the veins of an unsuspecting British public.

They themselves would be an era-defining outfit, a shapeshifting electronic dance collective that would define an era courtesy of an anthem for a generation.

The ‘80s were still stretching its arms out blinking into the sunlight, and adjusting to the one year anniversary in office of Britain’s first female prime minister Margaret Thatcher, when they hit the opening chord from their lofty vantage point, with views across the Welsh capital’s civic centre.

Music was blowing away the cobwebs of ‘70s excesses, the visceral thrill of punk and the new wave aesthetics of DIY indie were springing hope eternal.

Screen Gemz, as it was they who had taken to the rooftop of Cardiff University were similarly artful and creative in their approach to their musical stylings.

No wonder when their frontman Karl Hyde had spent the intervening three years undertaking a fine art degree at Cardiff College of Art living something of a bohemian existence in a ‘punk’ house in Riverside, near to the city centre.

Stuart Kelling, the guitarist in Screen Gemz, remembers that sunny May day vividly – a rooftop gig that just like The Beatles’ concert was also shut down by the police.

“This was one lunchtime on the roof of Cardiff Students Union,” he recalls in a post in the Screen Gemz / Freur Facebook group. “We were due to play with another band, and as we’d headlined with them as support a few weeks before, we agreed to play first.

“However, the sound drifted across to the Law Courts, the City Hall and other admin buildings, and we were told to stop just as we were finishing, which meant the other band couldn’t play. It caused quite a stir. Ironically, we’d just finished when the police told us to stop.”

The year before they hit the lofty heights, 1979, had seen Screen Gemz release their debut single ‘Teenage Teenage’ / ‘I Just Can’t Stand The Cars’ – two cuts of frantic Elvis Costello-like power pop in fitting with the prevailing mod / new wave scene that was in full effect that year.

Recorded in London at the studio of a mate from Cardiff who had escaped up the M4, the single embellished their burgeoning reputation in South Wales, where they were one of the most promising and eminently watchable bands on the Cardiff music scene.

Writing in his autobiographical diary ‘I Am Dogboy’, Karl Hyde lays out the background to The Screen Gemz and the rooftop show that would be the slow burn catalyst for what was to follow.

“I painted a backdrop, we discussed and designed stage clothes, called ourselves ‘Screen Gemz’ (spot the Z) and set to work playing bars and college halls all over town, growing an enthusiastic audience who warmed to our locally promising generic power pop, becoming ‘The’ band (for a while) in Cardiff,” remembers the musician.

“We found someone to call a manager, gave him a hard time and when Radio One broadcast for a week in the window of a Cardiff store I spent all night designing the cover of a folder of press shots with a cassette box of demos covered in pink latex.

“The music was a shadow of what the artwork promised and a paler shadow of what was already on the radio – no one played it, but they praised the presentation.

“We carried on gigging, reaching our zenith one summer playing on the roof of the Student Union building with our stage set of broken TV’s and giant yellow American fridge covered in red spots that opened to disgorge party balloons.

‘Like the original rooftop gig the police closed this one down, but not before a young student on an electronic engineering course had become temporarily smitten with the band.

“The young man’s name was Rick Smith.”

Surrounded by their offbeat ephemera and musical miscellany, the rooftop gig was an artistic statement on a student budget, but knowing you never get a second chance to make a first impression, the ramshackle stage set up didn’t stop the band from impressing all who were watching – and that one noticeable person in particular – the man who would soon begin a 30 year working partnership with Karl Hyde under the moniker of Underworld.

History is littered with chance meetings, of fate dealing its hand and synchronicity in action, but if there was no Screen Gemz, if there was no rooftop gig, if Rick Smith hadn’t bothered to show up that one sunny lunchtime, destiny takes a wrong turn and an altogether different story is written.

Invite

Rick Smith was studying Electrical Engineering at UWIST in Cardiff, and was one of Stuart Kelling’s best mates when they were growing up in Ammanford. After the rooftop gig, Screen Gemz changed personnel and Rick was invited to join the band.

“Rick was my bestie from when we were 14 or 15 (I grew up in Swansea, Rick in nearby Ammanford), and when The Screen Gemz (Karl, Alfie Thomas,, Steve Irwin and me) decided to replace keyboard player Gary Bond, I suggested Rick, who’d decided to come to uni after a relatively wild weekend on the town with me,” Stuart recalls.

“Rick and Alfie lived on Walker Road in Splott, number 35 I think. Their next-door neighbour was a retired navy cook called Smitty, in his mid-70s. A lovely old guy, famous for inviting anyone he liked in for lunch, which I accepted a couple of times. He was an amazing cook. He was also a hoarder, meaning you had to squeeze in through all the stuff and sit where you could to eat. He was also a victim of 35 burglaries in six months, and put a notice in his window, changing the numbers as they increased.”

Rick remembers Screen Gemz’ rooftop show as pivotal to their back story.

“When we met [in the late 1970s], Karl had recently finished art college and I was at the University of Wales doing electronics,” he told The Independent in 2010 in a story about how the pair met. “A good friend of mine (Stuart Keeling) was in a band with him, and they were desperate for a synthesizer player.

“I don’t know what I was thinking at the time. I’d never really thought about a career in music. I think it was just unbelievable stupidity on my part. They were one of the biggest bands in Cardiff, and I’d just seen them do this gig on the roof of the student union, and it seemed so glamorous. Then after a month I thought, “Shit, what have I done?”

Rick Smith’s roots were in the church. Growing up in the Swansea Valley, he played in his local chapel. His sister was a concert pianist, while his mother was a piano teacher.

At that time in the mid-70s when the church was updating its image and it seemed mandatory for every forward-thinking place of worship to have its own rock band, Smith had his first synthesiser bought by the church and he played in their rock band.

He dropped out of university to join Screen Gemz, however he departed soon after. Whether unimpressed by their rehearsing in a grain silo in Cardiff docks or the music’s derivative nature, he took his synthesiser, bought a Portastudio and began experimenting with electronics.

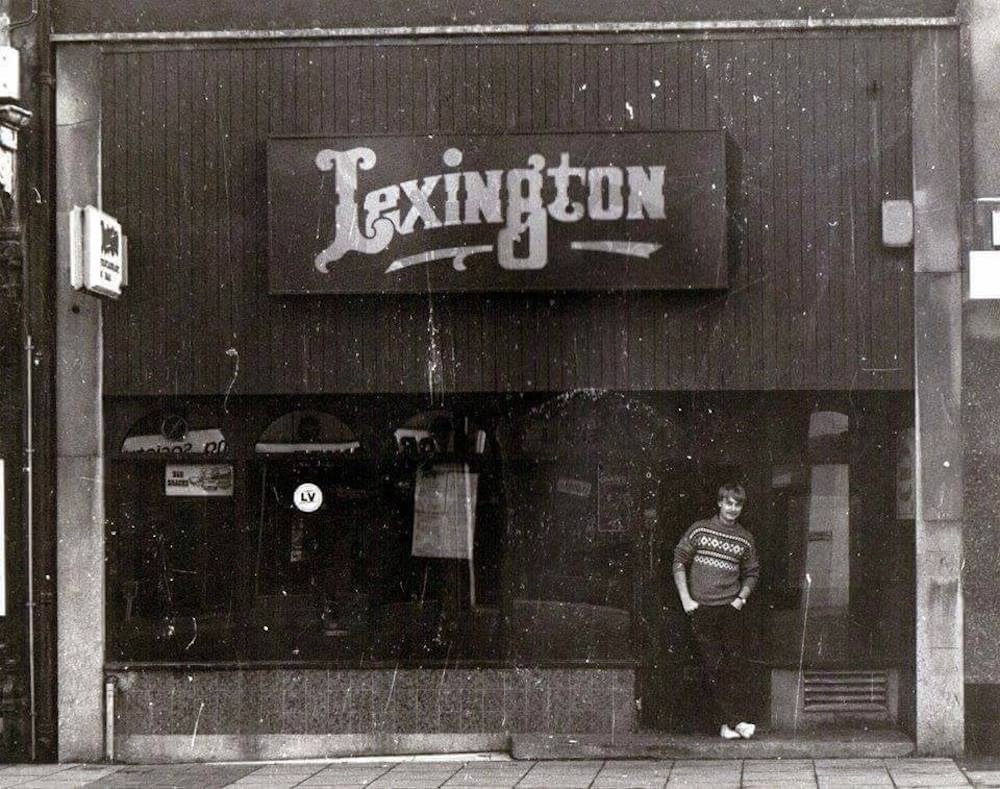

The pair continued to work together, in the kitchens of independent Cardiff hang out The Lexington – a diner / watering hole for the city’s alternative crowd.

Bonding over a shared love of Kraftwerk and Hawkwind’s Silver Machine, Hyde disbanded Screen Gemz soon after Smith had left, impressed with the direction his Welsh friend was heading.

“He was talking about the future,” Hyde remembers. “We started recording on borrowed drum machines, processing voices through guitar pedals, fusing Germanic electronics with Jamaican dub. We sent tapes to Peel in cornflake boxes with cornflakes in them – and he started playing them.”

Those of a certain vintage might remember the resultant band that emerged from these sessions, a group initially without a name save for what appeared to be a squiggle.

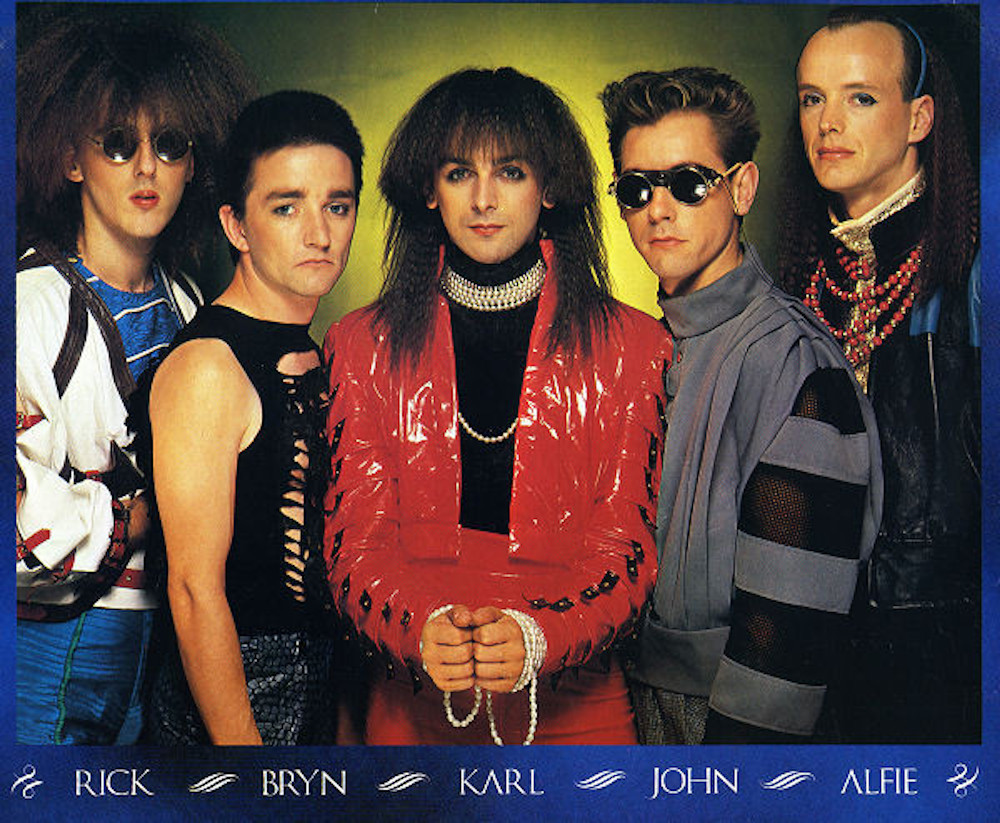

Before Prince (who Hyde later worked with) appropriated a symbol, the band that was to eventually become Freur adopted a squiggle as its moniker.

“We didn’t want to be like anybody else,” Hyde confessed to Record Collector magazine. “Everybody was wearing black as they were into Echo & The Bunnymen and Gang Of Four, so we wore bright colours and lots of hair and jewellery. Living next to a bunch of skinheads in Cardiff docks, that’s fascinating, an interesting way to live.”

Freur began to make a little money through exploiting their Welsh connections. At the time HTV Wales paid well if groups sang in Welsh. They’d sing phrases in the language, hastily learned from a friend, over and over again, making for some startling appearances on Welsh TV, including an unforgettable appearance on HTV’s Welsh language pop programme Sêr, where they were introduced by a young Caryl Parry Jones.

The group signed to CBS in 1982 and released their debut single ‘Doot Doot’ the following year. Combined with their looks, their squiggle and hair, the group seemed blighted from the off in the UK, despite having success in Europe, but little chart action in the UK.

“Because we were so poor and CBS offered us real money, we took the Queen’s shilling and decided to be a pop group,” said Hyde.

They spent part of their advance on a Chevy Blazer, a big pick up truck which they would drive around Cardiff attracting much attention.

Just as noticeable as their squiggle (and the truck), however, was their hair.

“There were three of us who be crimping, we were like monkeys,” Hyde recalls. “We’d be doing it in a circle. We had to get up an hour before everybody else to crimp. Bryn, our drummer had a crop. He had an hour’s lie-in everyday and a laugh.”

The whole project seemed ill-fated from the off, especially as Freur were not going to play ball, and behave like every other obedient pop group.

“They lined up all the papers for interview. We thought we’d help the situation by not adding to it. We said we didn’t want to do any press and that was the end of that,” recalls the frontman.

“We’d done the soundtrack as Freur for the film of Clive Barker’s Underworld, which became known as Transmutations, and then we became Underworld, this kind of rock dance band.”

After being the next big thing, the group – Hyde and Smith, plus fellow members Alfie Thomas Bryn Burrows and and John Warwicker were dropped by CBS, eventually ending up as Underworld MK1 in Romford in Essex.

That line-up released two albums – ‘Underneath The Radar’ (1988) and ‘Change The Weather’ (1989), bringing the curtain down on a decade that had started on a rooftop in Cardiff.

An extended hiatus until 1993 gave the duo of Hyde and Smith time to recruit DJ Darren Emerson and reinvent themselves as the electro dance giants we know them as today.

Two years later, Underworld’s anthem for a generation ‘Born Slippy’ appeared on the soundtrack to ‘Trainspotting’, the movie that more than any other defined the hedonistic, party-loving ‘90s – and the rest, as they say, is history.

Underworld then, from Cardiff to dance music canonisation. A 15 year overnight success story. Made in Wales.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.