War and protest: What war takes and what kindness gives back

Yuliia Bond

When I left Ukraine, I was not certain I would ever see my home again. bNot in a dramatic way. Not with panic. Just with a quiet, devastating clarity that this might be permanent.

I am from Eastern Ukraine, just a few kilometres from territory that was occupied in early March 2022.

Leaving was the most difficult decision of my life. It meant accepting that staying could cost everything, and that leaving might mean carrying grief for the rest of my life.

It was not a decision made with certainty or courage, it was a decision made because there was no other way to protect what mattered most.

I didn’t pack properly. I couldn’t. I grabbed what my hands reached for instinctively: my grandfather’s watch, photographs of my grandparents, family photos, photos of my children. A few small handmade things passed down from my great-grandmother and great-great-grandmother – objects that carried their hands, their lives, their care. And two cheap shirts. That was it.

I remember thinking very clearly: these are the things I must take. Everything else can be rebuilt.

These cannot.

When I arrived in Wales, I had nowhere to go at all. I didn’t know where I would live, where I would sleep, or what would happen next. But by that point, I was already so emotionally broken that it almost didn’t matter. Grief had gone quiet. Survival had taken over.

I wasn’t really able to speak about what had happened. And when I did speak, I never spoke really about it. I had completely lost my personality, I was a shadow of myself then, and in just a few months it felt like I had aged ten years.

Some experiences don’t arrive with words. They arrive as numbness, silence, and the instinct to keep moving because stopping feels dangerous.

Then two people in Caerphilly opened their home to me.

They didn’t just offer a room. They offered trust. And hosting someone who arrives carrying war, loss, and disorientation is not easy. It can feel like raising a child… or a stubborn teenager. And if I’m honest, I probably was a stubborn teenager.

Some days, I locked myself in my room and cried for hours. I cried for friends who had been killed. I cried thinking about my mum, who refused to leave and stayed. I replayed messages, imagined worst outcomes, counted hours, waited for news that might come or might not.

I was not easy to live with. I was grieving. But they didn’t ask me to be convenient. They didn’t ask me to explain myself. They stayed.

Slowly, they stopped feeling like hosts.

They felt like family.

A door opening

Around that same time, I met another Ukrainian woman. She had nowhere to go. People began asking around, trying to find her somewhere safe. And it was then that Jill Baird, a mother, asked her daughter a simple but life-changing question: Would you be able to host her? Her daughter said yes.

There was no hesitation. No conditions. No long discussion. Just a door opening. The Ukrainian woman moved in immediately and she stayed for a long time. Long enough for the sharpness of grief to soften, though never disappear. Long enough for survival to become something closer to life.

This is something I speak about with so many others who arrived here through war and displacement, and we all say the same thing: hosting is not a small act. It costs space, energy, patience, and emotional labour. It means sharing daily life with someone else’s grief, silence, and slow rebuilding.

And yet people here chose to do it. Quietly. Without guarantees. Without knowing how the story would end.

And I want to say this without softening it:

this kindness is never forgotten.

Not by me.

Not by those who were hosted.

Not by any of us.

This is why Jill’s exhibition matters so deeply.

Jill did not respond to war as an abstract idea. She lived alongside its consequences – through her daughter’s home, through witnessing what displacement does to ordinary lives, and how long grief stays.

Later, when she attended a protest in Cardiff against the genocide in Gaza, hearing recordings of bombs, seeing photographs of children, those sounds and images did not remain distant. They connected to something she already knew.

What war does to people.

What it takes from them.

And how deeply it stays.

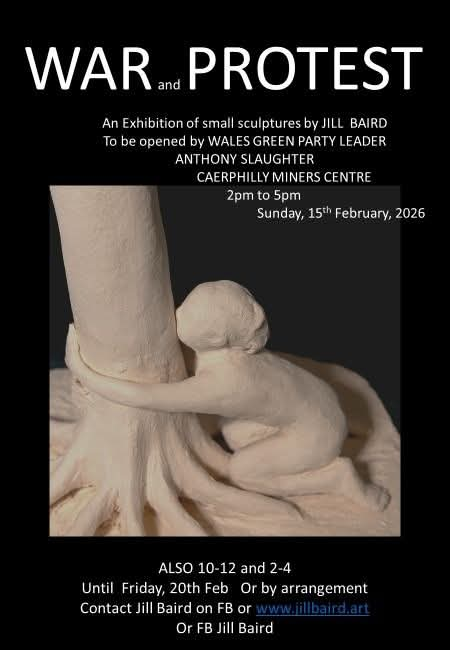

“War and Protest” grew from that understanding. These small paper-clay sculptures speak quietly, but relentlessly, about the human cost of war, not only in Gaza, not only in Ukraine, but everywhere. Some figures carry white flags. Not as surrender, but as a plea. A refusal to accept violence as inevitable.

Caerphilly Miners’ Centre

The exhibition will be hosted at Caerphilly Miners’ Centre and will be officially opened by Anthony Slaughter – Wales Green Party Leader

This moment matters, not as ceremony, but as public witnessing. As a recognition that these stories do not belong only to those who carry them, but to all of us who choose to listen.

The opening is on Sunday, 15th February from 2-5pm. There will be a short talk before 3 pm, followed by singing and poetry in the cafe. A small photo-book will also be available, with proceeds supporting Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders).

I will be there. Carrying my own memories.. of knowing that one decision can divide a life into before and after, and that one open door can make survival possible.

Please come.

Not to be comfortable.

Not to observe from a distance.

Come to witness.

Come to remember.

Come to stand with those who may never see their homes again and to honour those whose quiet courage, patience, and humanity made survival possible.

Because war destroys homes.

And hosting, supporting, says clearly and stubbornly: you still matter.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.