Welsh writer longlisted for Women’s Prize says ‘shame belongs to systems, not survivors’

Gosia Buzzanca

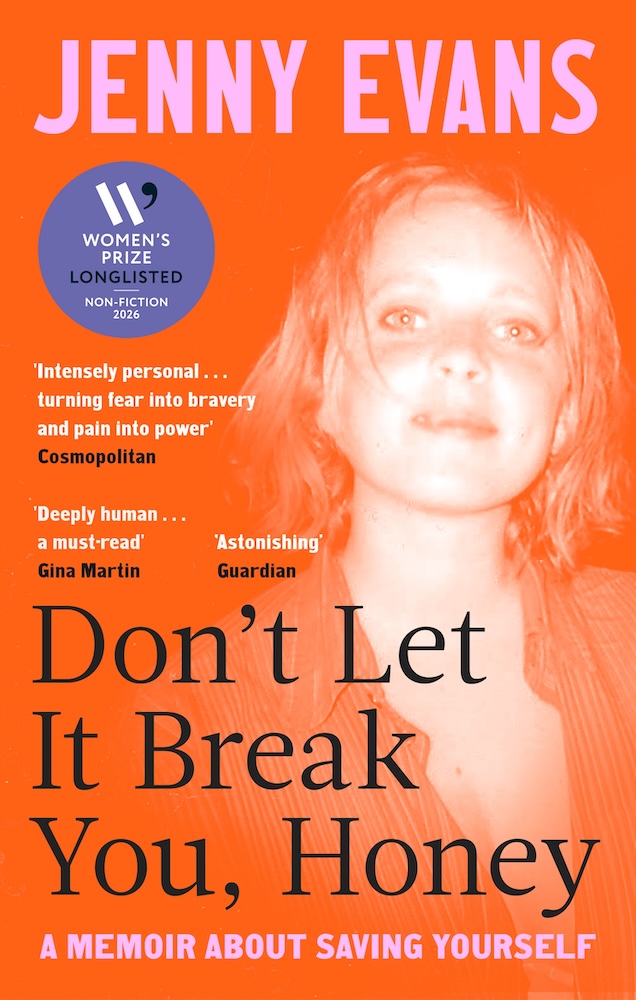

Longlisted for the Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, Don’t Let It Break You, Honey is a memoir that moves beyond personal testimony to interrogate power, shame and institutional failure.

The author, Jenny Evans, grew up in Abergavenny. Jenny trained as an actor, then as an investigative journalist, and now a lawyer, she brings a rare forensic clarity to the story.

What began as an attempt to understand how private information she had shared with police ended up in a tabloid newspaper became, over time, a case study in how institutions operate when accountability threatens reputation.

I spoke to Jenny about the risks of telling the story, the fear of shame and reduction, and the influence of a Welsh upbringing on her work.

Your memoir Don’t Let It Break You, Honey documents an incredibly painful personal experience that ultimately reshaped your life and career. When was the moment you knew you had to tell this story, and what was your biggest fear in doing so?

I trained as a journalist to find out how private information I had reported to the police ended up in a tabloid newspaper, so on one level writing the book was the final part of that investigation.

But it was a risk, so I subconsciously delayed, I think. Over the years I had reported on institutional failure again and again — in healthcare, policing, housing, social care — and I recognised the same pattern I had lived through: systems designed to protect people instead protecting themselves.

As I suspected when I trained, my story wasn’t just personal, it was a case study in power. But telling it meant personal exposure and vulnerability to a level I had to be ready to face.

My biggest fear was, and is, shame. Something I try and talk about in the book a lot.

The assault itself left shame, as all trauma does — though I am sure we all agree that wasn’t mine to carry — but how I might be judged, misunderstood, or reduced to one thing, and shamed. That was my fear.

Writing the book meant taking control of the narrative, but it also meant letting go of control over how it would be received. That was the risk. It remains a risk, but here we are. So far it has been well received. We’ll see!

Your quest for justice led you from acting into investigative journalism and then law. How did each of these fields equip you with different tools or perspectives in confronting institutional failure?

Acting taught me about voice and presence — how stories shape how we see people.

Journalism taught me how power actually operates: how decisions are made, how information moves, how institutions close ranks. It also gave me the tools to ask difficult questions and to follow evidence rather than assumptions.

Law has given me something different again: structure. Journalism can expose injustice, but law is one of the ways you can try to change outcomes for individuals within the system. It’s slower, more constrained, but it also offers routes to accountability that storytelling alone can’t.

Together, those experiences have shaped how I think about power — not as something abstract, but as something exercised through systems, language and process.

You grew up in Abergavenny and started your early career in Twin Town, a film often referred to as a cult classic with a distinctly Welsh spirit. How has your Welsh background and identity shaped the way you’ve navigated your personal and professional journey?

Growing up in Wales gave me a strong sense of community and a certain scepticism about hierarchy. There’s a cultural instinct to value people over status, and I think that has stayed with me.

There’s also something about being slightly outside the traditional centres of power that makes you more willing to question them.

And Twin Town itself was very Welsh in spirit — irreverent, funny, subversive. That sense that orthodoxy can be challenged, and taken less seriously than it wants to be, has probably shaped more of my career, and my character, than I realised at the time.

In the book you expose not just the assault itself but the systems that failed you; the police, the press, and power structures more broadly. What changes do you think are still most urgently needed in how institutions respond to assaults and survivors?

The biggest issue is culture rather than policy. Many of the right procedures already exist, but survivors still encounter disbelief, defensiveness or a focus on institutional reputation.

We need much stronger safeguards around victims’ privacy and data, clearer accountability when breaches occur, and better trauma-informed training across policing and the justice system.

We could also make it far easier to report. Why does it have to be to the police? Why can’t it be something therapists are paid by the state to offer, on the understanding that the information is held confidentially until or unless the survivor wishes to press charges? That would make reporting far safe and easier.

Because more broadly, institutions need to understand that how they respond after a report is made can be as consequential as the original crime. Secondary harm — through leaks, disbelief, or loss of control — is still far too common, and so harmful.

Many survivors find art or writing therapeutic; how did the process of writing your memoir affect your own sense of healing and agency?

Writing the book wasn’t therapy, it was closer to investigative work. Pulling together not just memories, and revisiting them in as much detail as I could muster, but returning to old notebooks, emails, sources.

What writing gave me was coherence. Trauma fragments experience; alongside trauma therapy with a skilled practitioner, writing helped me to put events back into a sequence and to find a way to describe it. As well as to describe the systems around what happened to me, rather than just my reactions and responses.

I guess the most important shift was moving from being the subject of the story to being its author. That sense of agency — of deciding what the story meant — was powerful. But I could only do that once Jemima Hunt at The Writer’s Practice, had backed me as an agent and Emma Smith at Little, Brown commissioned the story.

The most moving and important element was arguably being seen and heard by them, and encouraged to write.

Looking back on your journey: what advice would you give your younger self, and what would you most like your readers to take away from your story?

I would tell my younger self: what happened to you is not your shame.

And I’d tell her that institutions are made of people. They are fallible, sometimes defensive, sometimes wrong — and it’s okay to challenge them.

What I hope readers take away is that shame often belongs to systems, not individuals. And that voice matters — not just for personal healing, but because stories can expose patterns that would otherwise stay hidden.

If you feel disempowered, if you have been made to feel small, if you think you are out of options – ask questions. It costs nothing, and it gives you power.

What are you working on at the moment?

I’m looking for a job in law. I have done all the academic side and am now, somewhat unbelievably, am a Master of Laws, but I still need to do two years in a firm before I can qualify.

I am interested in women’s rights and public-interest work involving institutional accountability. But so are loads of other people, it seems, so – if there are any human rights lawyers out there reading this, feel free to give me a job.

Alongside that, I’m writing a Substack called We Need To Talk About Shame, which explores how shame operates in systems like healthcare, the justice system and therapy — and how it shapes silence, and us.

I’m also, as ever, developing several factual television projects that continue my investigative work around institutional power and accountability.

And I have an idea for my next book, which Jemima and I are talking about.

Buy a copy of Don’t Let It Break You, Honey here. Subscribe to Jenny’s Substack here.

More information about the charitable mission of the Women’s Prize Trust can be found here.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.