A St Valentine’s Day massacre: The Garden Pit Flood

Howell Harris

In the parish of Martletwy, on the eastern shore of the tidal Cleddau river in the heart of the Daugleddau region of the Pembrokeshire National Park, at the end of a narrow dead-end lane, lies Landshipping Quay.

It’s a quiet, unspoiled place nowadays — not even a hamlet, just a scatter of houses three miles from the nearest small village.

The Quay and its neighbourhood, now entirely rural, do not strike the casual visitor as the sort of place where, a century and a half ago, you would have encountered a major industry. But until the 1850s Landshipping was one of the main anthracite coal producers in the county and the site of several active pits.

Mining has left hardly any visible traces. Even the Quay itself is more than half ruined, much of it just a pile of stones. But in the first half of the nineteenth century thousands of tons of anthracite were exported from here every year.

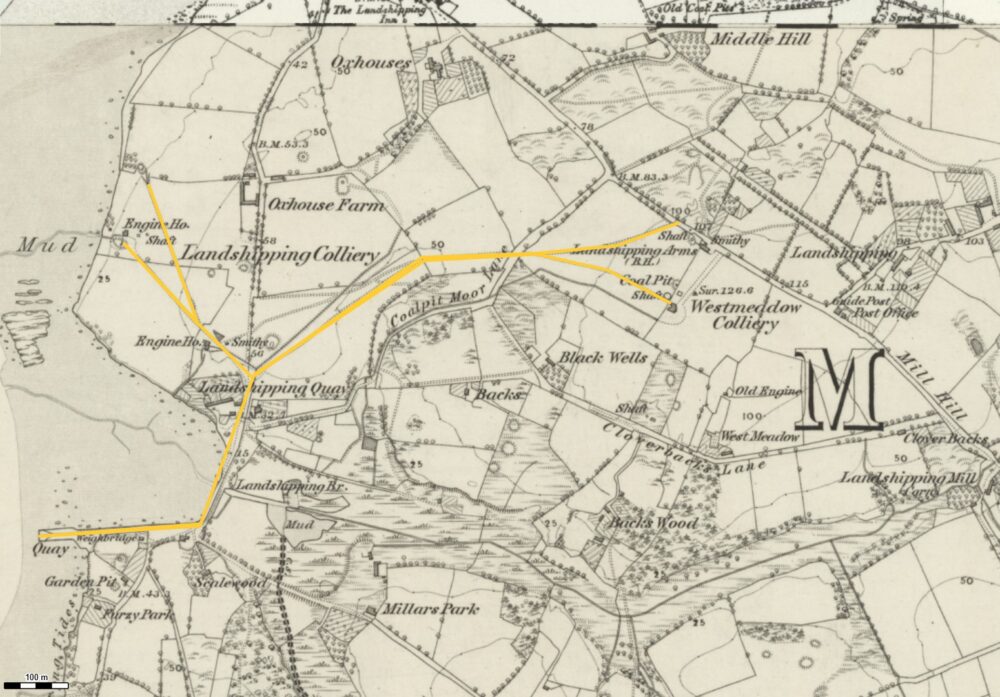

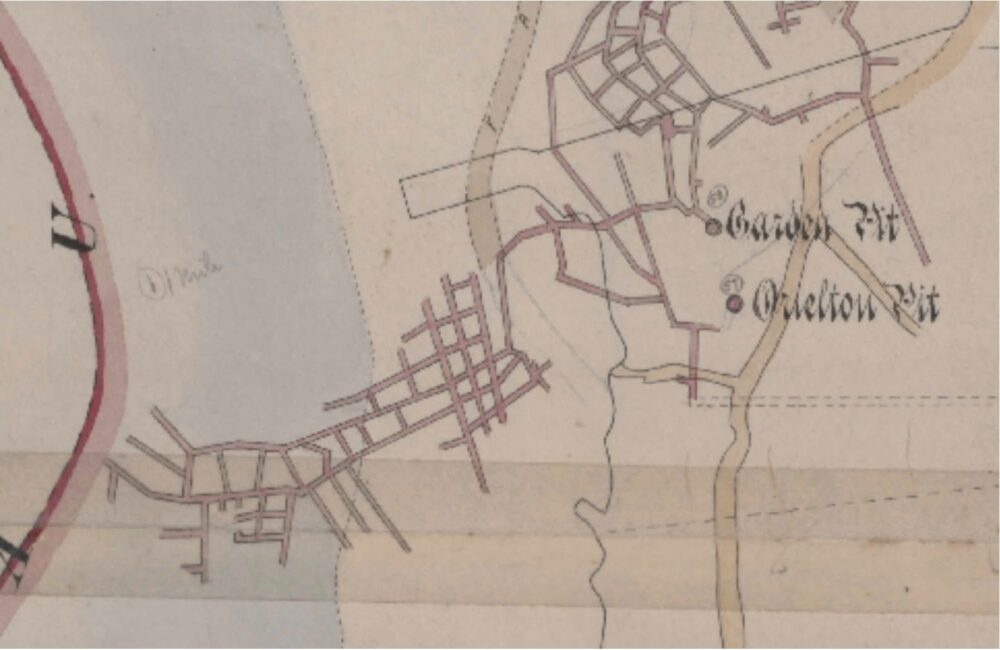

A tramway ran across the causeway (marked “Landshipping Br[idge]” on the map) from pits to the north and east of the Quay, past the mine manager’s house and office.

Two tall chimneys for the mines’ steam engine boiler houses punctuated the northern skyline. Nothing remains of any of this industrial landscape apart from an old lime kiln and the manager’s house, now half-renovated.

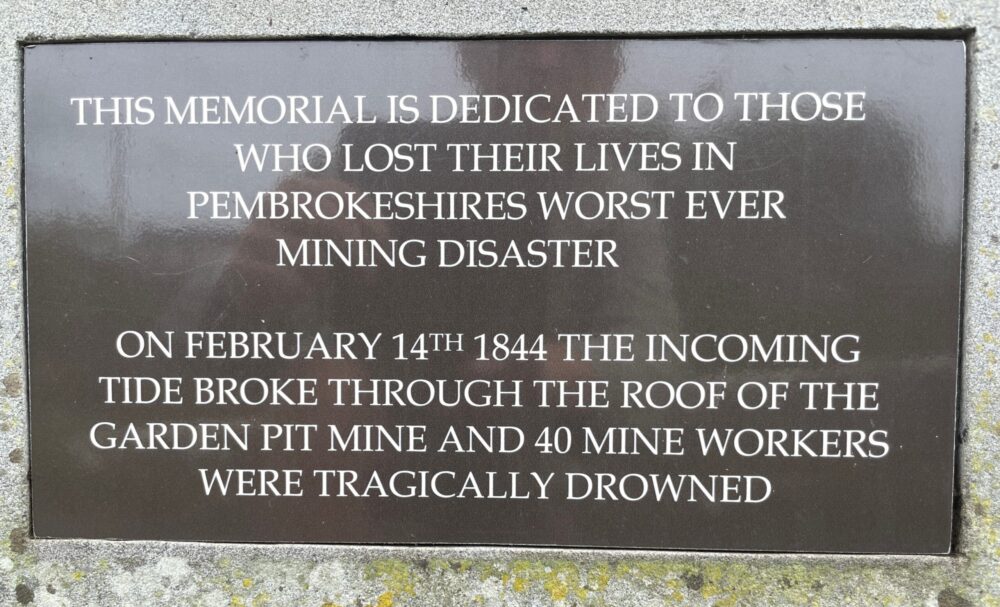

It happened at the Garden Pit, located thirty yards south of the Quay and only a few yards above high water, when the thin rock roof of a shallow seam collapsed and the tidal river flooded through.

The Garden Pit tragedy killed 40 men and boys in a few minutes, the largest death toll in a single incident in the county’s mining history and a major accident even in national terms.

That was about a third of the Landshipping pits’ mining workforce, and two-thirds of the men and boys down the pit that fatal afternoon.

There were only two worse flooding ‘accidents’ in the whole British mining industry in a century of coal, one at Heaton Main pit on Tyneside in 1815 (75 dead), the other at Audley in Staffordshire in 1897 (77 dead).

Both happened in much larger pits than the Garden, and much bigger coalfields than Pembrokeshire’s.

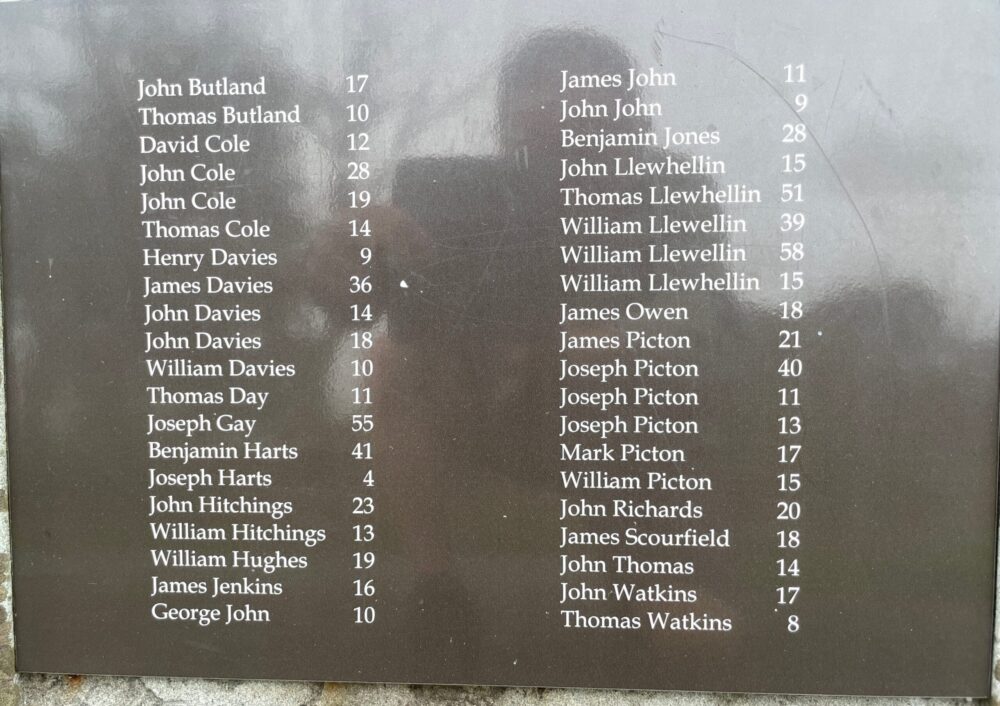

What is even more arresting than the thought of so much death, so quickly, and in such a now-beautiful and tranquil spot, is the second plaque on the memorial listing the names and ages of the victims.

The youngest was just 4, and four of the dead were children below 10 years of age.

According to the 1842 Coal Mines Act they ought not to have been there at all. Fifteen were boys and early adolescents aged between 10 and 15, while ten more were young men between 16 and 20. Altogether, about one in seven of the community’s boys and young men between 8 and 20 died that day, and a far higher proportion of those from mining households.

The other eleven victims were adult men — eight in their prime working years, 21-41, three of them elderly survivors (51, 55, and 58) in a community where most miners died of lung diseases in their forties, if they lived that long. Altogether, about one in thirty of the community’s men died, a much smaller toll than among their children.

Most of the victims shared the same few surnames as between one and five others. Ten of the dead were members of the closely related Cole and Picton families – a quarter of the fatalities but only one ninth of the parish’s population.

The mine’s underground workforce consisted of fathers and uncles, cousins and brothers and sons. Some of their womenfolk, young and older, still worked on the surface.

According to Colonel Hugh Owen Owen (b. 1803), son of the mine owner Sir John Owen of Orielton (b. 1776), in 1841 about a third of their mining workforce was under 18, and a third of those were under 13 – twice as many as were reported in the census that year.

A fifth of the total was made up of women and girls, none of whom were recorded as mine workers by the evidently unreliable census.

Family bonds recruited and disciplined the underground teams – adult male hewers at the coal face wielded their leather straps to motivate their young helpers when necessary.

This meant that when disaster struck family members died together too, while their female relatives at the surface witnessed the immediate aftermath. Many of the victims that day even died at the hands of a relative: the mine overseer was a James Cole.

Colonel Hugh, a stalwart supporter of the Church Missionary Society, was clear in his testimony to the Children’s Employment Commission in 1842 that his mines needed this diverse workforce.

Young children were the best and cheapest for light jobs like opening and shutting ventilation doors. They “do the work easier than large ones and where wages are low they are preferred.”

“I know of no machinery which would render the non-employment (sic) of very young children unnecessary, nor do I think it practicable.”

Slightly older ones were essential for moving the coal from the face. They “push the waggons and each child, if a strong one, say of 14 years of age, pushes the waggon upwards of 50 yards or two younger children do the work of one.”

The wagons contained less than a quarter-ton of coal each, so the work, he said, was not excessive.

Nor, he claimed, were the hours. “[L]imitation of the age at which children should work in mines is not necessary as they are not tasked above 10 hours either day or night. They work the same number of hours as the men,” and were treated the same as adults in other respects too — paid their regular wages when missing work through injury, allowed to take the dangerous ride up and down the shaft with no special care.

A mere two years after the Coal Mines Act’s passage, it was no surprise that it had not succeeded in excluding very young children from the mine altogether. It was only with the greatest reluctance, and quite gradually, that the industry accepted the 1842 Act’s prohibition of the employment of women underground too. But fortunately for them there were none down the Garden Pit that day.

Landshipping as a Mining Centre

The Pembrokeshire coal mining industry was old-established, mostly quite small-scale, and technologically primitive, but the Landshipping collieries were somewhat bigger, and comparatively modern for the area.

The anthracite seams at Landshipping in the area north of the Old Mill fault, which ran a couple of hundred yards south of the Quay, were far less geologically disturbed than in much of the rest of the field. The Orielton estate saw the potential for exploiting them on a larger scale by bringing its mining operations up to date.

Most of this modernisation took place under the management of John Colby, squire of the great Ffynone estate in North Pembrokeshire, while his nephew Sir Hugh Owen (1782-1809) was a minor. Colby, who had extensive anthracite interests of his own, installed the first steam engine in the county in 1800 to pump out Landshipping’s very wet mines and allow them to go deeper. He also built the quay in 1801 so that seagoing vessels could more easily pick up cargo, and encouraged the development of related industries (a limekiln, a brickworks) to take advantage of the estate’s mineral resources and location.

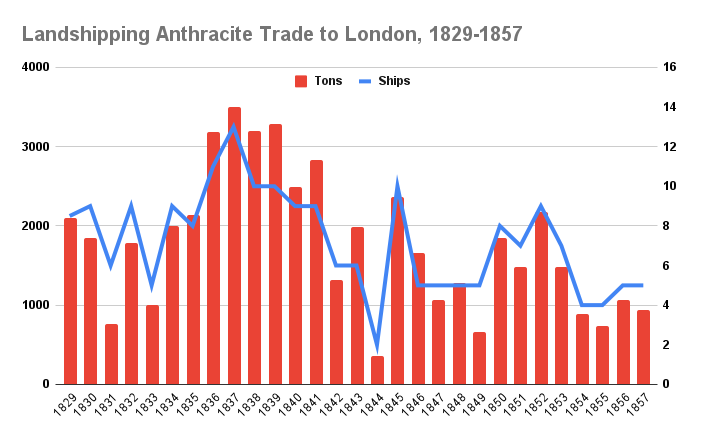

By 1801 the Landshipping pits were exporting 11,000 tons of anthracite a year, some of it particularly favoured by maltsters, hop-driers, and later steam ships too, for its high carbon content, low percentages of volatiles, sulphur, and ash, and consequent clean burning. It commanded a correspondingly high price — 60 percent more than soft (bituminous) coal in the London market; it was “anthracite in its purest quality and most beautiful form.”

After Sir John Owen inherited in 1809 he continued the estate’s development, or at least its exploitation, for the next half-century. In 1810-1811 he completed Colby’s work by installing a small network of iron tramways to bring coal from the pits to the Quay.

Scolton Manor Museum, Pembrokeshire County Council Museums Service.

The Rich Men in their Castles, the Poor Men down their Pits: The Owens and their workers

The blessings of industry were neither very numerous, except for the Owen family, nor widely and equally shared. Working conditions in their wet, gassy, poorly ventilated mines were horrible and produced multiple-casualty accidents as well as chronic ill health and early death.

Work was unsteady, insecure, and paid little better than agricultural labour, even for adult men. Housing conditions were primitive, and the Landshipping school was a one-room disgrace.

Colonel Hugh lived in the Big House at Landshipping Ferry, which he extended and modified to mirror and mimic the genuinely medieval Picton Castle facing him across the river. He generally supervised his own works in person when he was in residence there, but in 1841-1842 he and his father had been forced to escape abroad, attempting to avoid their creditors.

This was not a new problem for them. Orielton estate stumbled from one financial crisis to another from 1812 onwards because of Sir John’s lifestyle of “much magnificence,” in his grandson’s words, and his extreme open-handedness and generosity — which did not, however, extend to his workers.

Sir John was also burdened by the cost of unwise or unfortunate land purchases and the massive expenses required for supporting his mother and his predecessor’s widow, absorbing his younger brother’s bad debts, educating his sons, and marrying off his daughters. He could probably have survived all of this via land sales and mortgages, but the enormous price of buying his and Colonel Hugh’s seats in Parliament in a succession of dirty, sometimes bitterly contested elections finally broke him.

In 1831, the most costly of all, the polls were kept open for 15 days, electors were transported from all across the constituency to Haverfordwest to vote, and “the whole county was kept drunk at the expense of the candidates.” It was the ruination of the Owens. In 1838 they took out even heavier mortgages and Colonel Hugh had to give up his seat in Parliament, then in 1842 they were compelled to sell all of their great house’s furniture and silver plate to stave off bankruptcy.

derelict since 1890, but in the process of (very slow!) restoration for the last twenty years.

By 1844 Colonel Hugh was usually back in the county, but on Valentine’s Day he was away visiting his father-in-law, Sir Charles Morgan of Tredegar Park, whose 40,000 acres and many industrial interests dwarfed his own.

In his absence James Cole, his overseer, b. 1807, got on with the vital task of starting to produce coal and revenue again after a long midwinter shutdown.

The Landshipping mines’ lucrative trade in their prime London market had been in decline for years at precisely the time that financial burdens on the Owens became crippling, so the more local market in culm (finely shattered anthracite), usually at least four-fifths of a mine’s output, may have become increasingly important to them.

So Cole decided, or perhaps Owen had instructed him, to open up a district of an old mine, the Garden Pit, that had not been worked recently but contained a handy seam of good quality culm.

The Bright (or Tumbling) Vein was 4’6″ high and just 60 feet down. The Timber Vein, 7 feet of top quality anthracite that had been the Landshipping pits’ most lucrative target for years, was at the pit bottom, 150 feet deeper, and though much more valuable it was also more expensive to work.

The reason that the Bright Vein of the Garden Pit had not been worked for a couple of years was that it was very wet, even by local standards, and considered unsafe, particularly because the water entering the mine was salty and obviously from the river. But Cole sent his miners down regardless.

One story told by a survivor, twenty years after the event, was that on Wednesday 14th an old miner who had lost the power of speech noticed an increase in the inflow of water, but nobody paid him any heed when he attempted to tell them.

In fact other miners did notice, and they acted to save themselves: they were so worried that they all came back to the surface at the end of the morning.

But Cole (or, the survivor said, Colonel Hugh; but according to press reports he was a hundred miles away at Tredegar Park) reassured them that all was well. He ordered them back down in any case, or they would never work at Landshipping again. An hour later most of them were dead.

In the middle of the afternoon, when the tide was flowing and beginning to cover the mud banks, people at the pithead noticed a violent commotion in the waters about 40 yards from the quay. At the same time men working at the surface felt a strong blast of air up the mine shaft powerful enough to lift the arm of a man stretching out his hand across it.

Underground workers, much closer to the site of the roof fall and sudden inrush of water and mud, were blown off their feet and had their candles extinguished by a storm wind stronger than any they had ever felt before. They heard the roof collapse and the river flooding in.

Most of them had no chance. The roof fall was quite close to the bottom of the shaft — perhaps 70 yards away. Thirty-three of the 40 men and boys who died had been working the other side of the point of inundation, in a “drift” extending a quarter of a mile under the river where they would have been killed very swiftly by crushing, drowning, or both.

The 25 who had somewhere to run to sorted themselves into the quick and the dead. Some thought it was just another fire damp (methane) explosion and waited where they were before reacting. Their indecision was fatal. But 18 men and boys (4 men, 14 boys) made it the short distance to the shaft.

They either jumped into one of the pair of man-carrying buckets fortunately sitting there, clung to the rope that lifted them, or climbed the sides. The quick-thinking man at the “whim” (the horse-powered capstan powering the bucket elevator) drove his three startled draft animals at the gallop until all who could be saved were safe.

The luckiest men at the pit were the foreman (Cole himself?) and four other miners, who were planning to join their fellows underground in a few minutes’ time, where they would probably have added their names to the casualty list.

Filthy water

The pit flooded at 7 fathoms (42 feet) a minute. The shaft soon filled with filthy water and debris, and as some of the other Owen mines at Landshipping Quay interconnected with the Garden Pit underground they flooded quickly too.

Even those that were not connected found their ability to operate restricted. Years later the Westmeadow pit still dared not extend its own workings too far, because of fear about breaking through into the flooded areas and uncertainty about where these stopped.

Shocked quiet settled over the site. And then the scale of the calamity became clear, and the air filled with the sound of survivors’ and victims’ dependents’ screams and lamentations.

The news reached the outside world within days. There was plenty of coverage in regional and national newspapers, but almost all of it depended on a couple of rapid local reports, either quoted verbatim or digested. After a few weeks they reached the United States, and three months later the Australian colonies too, where the Owen family had substantial property.

The local reports established a clear, simple, and misleading narrative. The deaths were just a “melancholy accident”; the cause was the “weight of water” on the pit roof. Nobody was to blame, as “the persons whose duty it was to survey the work had considered it safe,” or, to put it another way, Cole’s and perhaps Colonel Hugh’s reckless lack of judgment meant that they bore no responsibility for its catastrophic results.

Culpability could not be attached to the men either, who were still engaged in preparatory operations after the long closure. They had not even started on the work of cutting coal that might have further weakened the thin, fragile roof.

Instead the blame was simply attributed to a spring tide — the mine “had never before worked at high water,” which is hard to believe, as these happen twice a day for several days a month. In any case the most recent spring tides had peaked on the 6th, i.e. by the 14th the tides were only just past the neap, with the next high springs in six days’ time.

But as the accident happened at less than half-tide, and the mine had hardly begun to be worked, the state or height of the tide can scarcely have been very relevant. It was a convenient explanation, but it was wrong.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.