Bringing Sioned to light: Translating Winnie Parry’s Welsh classic

John Ifor Wyburn

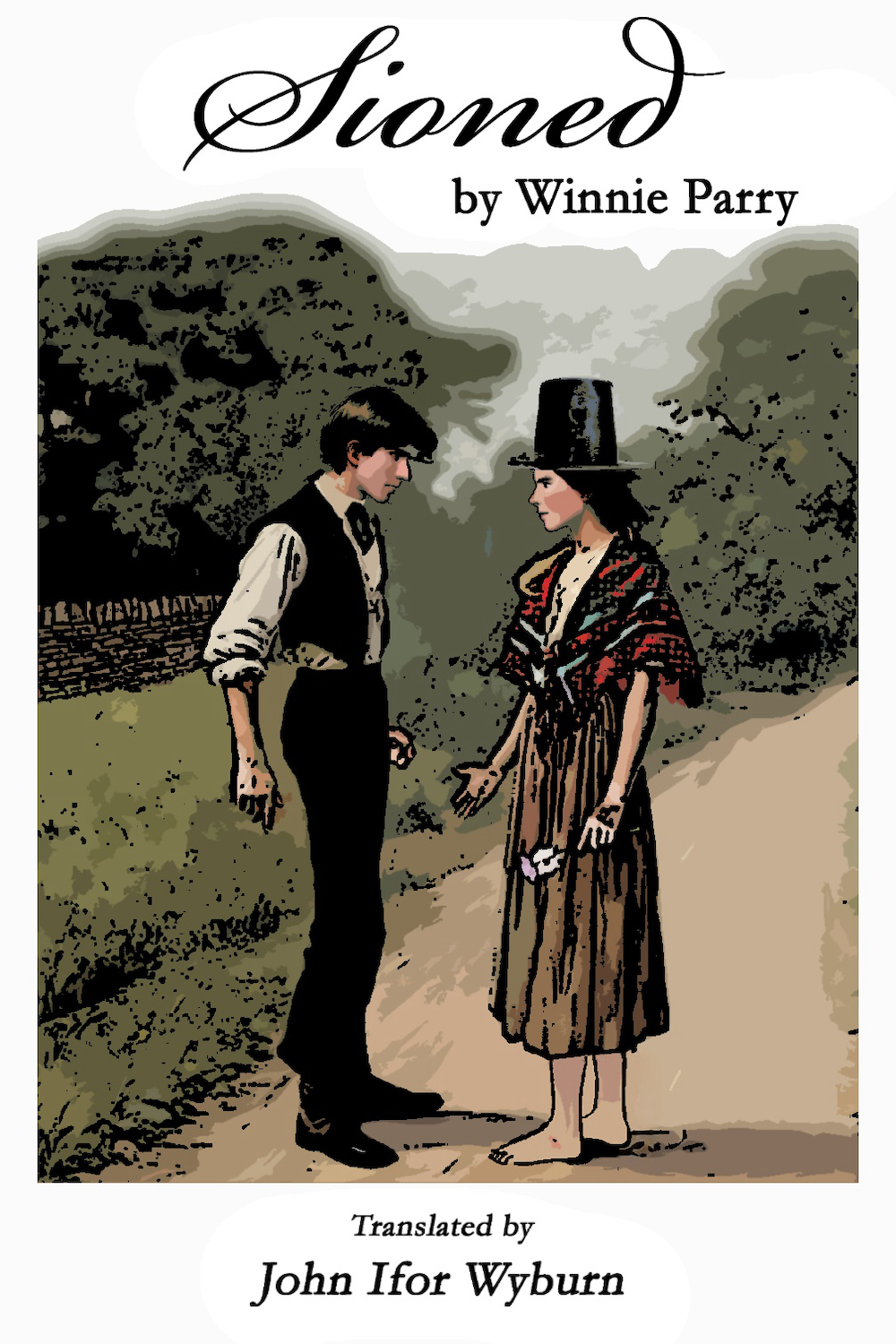

First published in 1906, Sioned by Winnie Parry was once a favourite of Welsh-speaking readers but never appeared in English. Now, more than a century later, a new translation hopes to share this coming-of-age tale of Victorian Caernarfonshire with a wider audience.

Winnie Parry’s Welsh-language novel Sioned was first published in 1906. Like Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm or Anne of Green Gables, it is a coming-of-age story, but one rooted in the fields and chapels of Victorian north Wales.

Its heroine, Janet Hughes (“Sioned” to her family) is clever, mischievous, sentimental, funny and self-deprecating. Her brother Bob acts as her conscience, and she values herself only in so far as Bob does. When she learns that he will soon marry her friend Elin, Janet faces the painful prospect of losing him. Over the next three formative years she must learn to find her own sense of worth.

Unlike her literary cousins, Janet has no single life-defining event (What Katy Did), little formal education (Anne of Green Gables), and no unshakable optimism (Pollyanna). Instead, she takes life as it comes, with all its knocks. Victorian Caernarfonshire, and briefly London, offers plenty of them.

By the late 1920s, Winnie Parry had become a household name through her novels and short stories, though she had already set aside her literary career to serve as secretary to the MP Robert Thomas. Interest in her work remained strong in Wales. A radio adaptation of Sioned was planned in 1947 but never broadcast (the script survives in BBC Box 145 at the National Library of Wales).

When I lectured at the University of South Wales, Sioned was sometimes fondly remembered by students, but only by Welsh speakers. Interest from fans of Pollyanna or Little Women quickly evaporated when they discovered there was no English translation.

I did not read Sioned myself until the Covid lockdown, part of an effort to improve my Welsh. The book struck a chord. I realised I was reading the Welsh What Katy Did; an extraordinary best-kept secret of Welsh literature. By the time I retired, I knew a translation would not appear unless some enthusiast made it their project. I am a second-language Welsh speaker, far more comfortable with the written than the spoken word, but my familiarity with the text persuaded me to make the attempt.

The original novel is in the public domain, which frees a translator from legal obstacles. But there are responsibilities. A literal translation is inadequate for modern readers: shared context, cultural references and even everyday knowledge can no longer be assumed. Added explanation is essential. Parry herself frequently reports the outcomes of conversations rather than dramatizing them (“telling not showing”), which modern readers find unsatisfying. Yet too much expansion risks misrepresenting the author’s intent, assuming the translator has understood this. The translator therefore has a creative responsibility of their own.

The first challenges were linguistic. Parry’s Caernarfonshire Welsh of the 1890s is different to modern southern Welsh. Words such as deci̇n (for tebyg), giarat (for closet or garret), or wesul tipyn (for fesul tipyn) do not appear in Y Geiriadur Mawr. So a lexicon had first to be assembled (the online Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymraeg was very helpful here).

Rich prose

Welsh prose is often thought long-winded, and sometimes it is. But repetition can be meaningful. When Pero the dog campaigns to claim the fluffy mat in the parlour, the repeated mi…mi turns prose into something like a comic poetic skit. This has to be conveyed creatively in translation.

Parry’s prose is rich in idioms. Where possible I have used English equivalents. When those seemed unsuitable or anachronistic, I drew on context or derivation to create my own. So “Dyn annwyl!” literally “Dear man!” becomes “Dear me!” quite straightforwardly, but my rendering of “Bobol bach!” as “Fairy mischief!” has raised some eyebrows among colleagues. I admit this to be whimsy in my Note on the Translation; after all, no one seems sure of the phrase’s origins.

The time difference required careful handling. This is not the age of the microwave and the mobile phone, but of the coal-fired oven and the daily post, if you catch it. When a maid from a neighbouring farmhouse rushes to report a child with a sore throat, this is no small matter. It might be scarlet fever, tuberculosis, or diphtheria. Or take the pepper with which Sioned innocently torments the preacher Jacob Jones: in her world, pepper might be adulterated with red lead and mustard, and the “sneezing” she finds so funny is a form of poisoning. No wonder Bob is furious with her.

Why has it taken over a century for a translation to appear? Long delays are common. Caradog Prichard’s Un Nos Ola Leuad waited 34 years; Islwyn Ffowc Elis’s Cysgod y Cryman waited 45. Parry herself may have resisted the idea of translation. Although she supported republication efforts in the 1940s, these remained firmly Welsh-language, as far as I can discover.

Why translate from Welsh to English at all? I believe the dominance of English media is the greatest threat to the future of Welsh. But global respect for Welsh literature depends on access. Works such as Tŷ yn y Grug and Wythnos yng Nghymru Fydd are now known beyond Wales precisely because they have been translated. Without such books, how do we answer the question: “Why preserve Welsh? What is it giving the world?” Translations also matter for the Welsh diaspora in the USA and the Commonwealth, offering a way to experience the culture of their origins.

I hope that Sioned: A New Translation will bring this overlooked classic to a wider audience for the first time. I’m under no illusion that it will transform global perceptions of Welsh literature. But each book that crosses the language barrier helps. My hope is that Sioned will join the chorus of voices proving why Welsh writing, past and present, deserves to be heard around the world, and that it will entertain while doing so.

You can purchase John Ifor Wyburn’s English translation of Sioned HERE

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Da iawn, dal ati!

Dolch yn fawr!

Diolch yn fawr! (Arthritis truenus)