Del Hughes has a dead good day out

Del Hughes

It’s a splendid Saturday, with empty blue skies, a dazzling sun, and a briny breeze sweeping in from the bay, blending beautifully with the heavy scent of wild garlic.

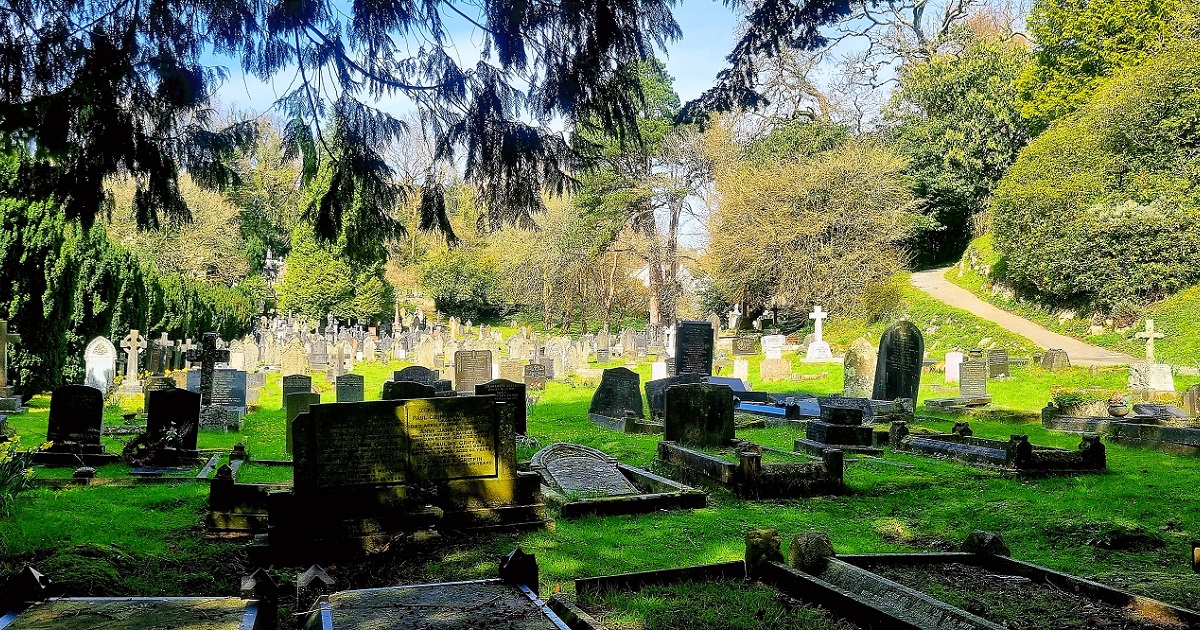

Spring is blooming in glorious technicolour, and banks of crocuses, daffodils, and bluebells soften the rough edges of the gravelled pathways that trail through avenues of yew.

With birdsong, and the gentle breath of nature, muffling the constant grumble of 21st century living, it’s the kind of day that makes you glad to be alive. . . which is somewhat ironic because today I’m at Oystermouth Cemetery, waiting for a guided tour of notable graves, gothic tombs, and the occasional celebrity corpse.

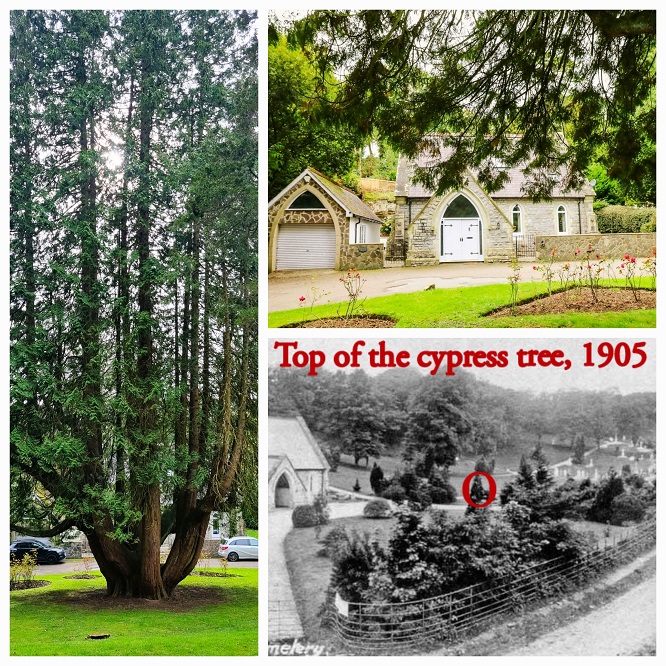

I’m perched on the old stone wall, beneath a seriously impressive cypress tree, and – as I later learned from Bev (our guide) – it was no wonder this bad boy was so imposing because it had a personal history spanning well over a hundred years, and an even more ancient mythology.

Long story short: a teenager named Cyparissus had a pet stag he dearly loved – though not dearly enough to check the surrounding woodland, prior to his daily javelin practise. (Eye roll. But that’s kids for you.)

When he found the lifeless body of his antlered pal, Cyparissus’ grief was so all-consuming, he prayed to Apollo that he be allowed to mourn forever.

Apollo, aware that forever is a very long time, and knowing the fickleness of youth, said, ‘C’mon Kid, think what you’re asking for!’ But still Cyparissus grieved.

So, in my opinion, going slightly OTT, Apollo transformed him into a cypress tree, and that’s why it’s seen as a classical symbol of mourning.

(Poor Cyp. What he’d really needed was a night out with the lads, a shoulder to cry on, and several bottles of Ouzo, and I’m sure he’d have bounced back eventually.)

Timeless tranquility

Anyway, as I waited beneath the sad tree for Bev, and our tour group, to arrive, I felt that I could easily be back in 1883 (which is when the cemetery first opened), if I ignored the parked cars, and a charming chap on a scooter, who shot past with a cheery, ‘Move, Grandma!’ Sigh.

But, despite such reminders of the here and now, there was a timeless tranquillity that made this a perfect place to rest in peace.

In fact, I was just picking out a theoretical plot for myself and Tim – though it’s unlikely he’ll stick around in the afterlife because my snoring is, apparently, so loud, he ‘can’t put up with that racket for sodding eternity!’ – when Bev arrived.

I’d guessed it was her because she was clutching a folder of notes and, more of a giveaway, had a smiling skull scarf draped around her neck. She was not at all what I’d imagined.

I’d envisaged her draped in black crêpe, face covered by a mourning veil, with a persona that was sombre, sad, and deathly serious.

But Bev was all smiles, very welcoming, and I started thinking that this tour might actually be fun – or at least, less solemn than I’d anticipated. And I was spot on.

Burial customs

Bev kicked things off by telling us a little about her background. As well as a folklorist and researcher of burial customs and superstitions, Bev is also a Master of Death, Religion and Culture, which is without question the most epic academic title I’ve ever heard.

But I wondered aloud what caused her to spend a lifetime investigating such a morbid topic, and she’d laughed.

‘Morbid? Not a bit of it.’

Instead, she recalled halcyon days, picnicking in Birmingham’s Whitton Green Cemetery, a place that six-year-old Bev felt was made for leisure and enjoyment – and which was exactly what Victorian architects were aiming to achieve with their new, gardenesque cemeteries.

En route to our first grave, Bev fed us fascinating snippets of folklore and trivia. The difference between cemeteries and graveyards? Umm?

Basically, if there’s an active parish church on site, it’s a graveyard, otherwise, a cemetery.

And the small stone mortuary chapel, built to allow relatives to pay their respects prior to burial, is now privately owned, having been sold in 2001 as a ‘unique residential opportunity.’

Bev had actually put in a bid at the time, it being her dream house, but sadly missed out, and now it’s an Airbnb for those looking for a dead quiet holiday let.

Regenerative

We passed through tilting yews, planted by the first caretaker of Oystermouth, Henry Harris.

Someone asked why they were so common in burial grounds and Bev explained that they’re a regenerative tree; when the branches reach the ground, they can take root and form new trees, and this ongoing cycle of ageing and rebirth came to symbolise death and resurrection.

But folklore also suggested that they kept evil spirits in check, so when Bev said that they’re an ‘absolute nightmare,’ I sensed a spooky story was in the offing.

‘No, nothing scary. It’s just difficult keeping them all upright because they’re inclined to lean. It costs the council an absolute bomb every year to deal with them.’ Lol!

As we walked, it became obvious that Oystermouth had a muddled mixture of Victorian gothic memorials, uneasily rubbing shoulders with minimalist, modern neighbours.

Bev explained that back then, you could trot along and secure any plot you fancied, anywhere in the cemetery, and the long-term organisation wasn’t a particular consideration.

‘That’s why the earliest graves are randomly dotted throughout the site.’

However, that changed in the 1930s when a chronological system was introduced, leading to the more ordered plot layouts you see today.

Superstitions

She told us about other superstitions that often haunt such places. How it was believed that the first person buried in a new cemetery had to remain there, in spirit, to guard it against the Devil.

So, in order to prevent a human soul from being forced to perform such a duty, a dog would often be buried in the north part of the churchyard, prior to any human interments. Eh?

Though I guess it makes sense – ‘Man’s Best Friend’ would definitely make a most loyal and effective guardian.

Bev wasn’t sure if Oystermouth had followed this tradition, but one family who probably hoped they had, were the Gelderd’s, whose son, Alfred, was the first person buried there in March 1883, aged just twenty-three.

Our first stop was at the rather humble grave of one Thomas Harry, a schoolmaster who died in the autumn of 1915.

His ‘bedstead’ plot was quite unremarkable, so it seemed an odd place to begin.

But a closer look showed why this was noteworthy – and if any of you chuckled over a news item last week about a spelling error made by Swansea gas workers, this is in the same vein. . . though I guess repainting is much easier than doing the carving equivalent of Tipp-Exing a slab of granite.

Symbolism

And then we dived into the strange world of Victorian death symbolism.

Symbols became popular additions to grave markers during this era, not only from an aesthetical standpoint but also due to widespread illiteracy – symbols made memorials more meaningful for those who weren’t able to read the words.

And, as might be expected, the most common were crosses, signifying the deceased’s faith, love, or goodness.

Bev took us past a variety of styles, from the plain to the florid, Celtic to fleur-de-lis.

Angels

Then came the host of angels, which to my untrained eye, were much of a muchness.

But Bev pointed out subtle (and not so subtle) differences, explaining that their meaning would alter, depending upon their pose.

It was a way in which the family could silently convey characteristics of their deceased loved one.

An angel in flight implied rebirth, bibliophile angels, surveying scroll or book, indicated the deceased had a history of good deeds, while praying angels suggested a pious life.

My least favoured were the weeping angels who frequently indicated an untimely, or painful, death. Gulp. Doctor Who has a lot to answer for – I didn’t blink the whole time I was there!

Clasped hands

We stopped at Bev’s favourite grave, and I was, initially, a bit disappointed.

No urns or angels here, just a carved headstone showing two clasped hands, one a tad bigger than the other.

But looking closely, you could see that the cuffs were slightly different – one starkly masculine, the other edged with lace.

Such symbology intimated that John, or Archie, would be on hand to guide sister Effie into the afterlife, where all three siblings would be reunited. Aww. It was a lovely sentiment.

The indescribable

And then it was uphill, to visit a grave which attracts people from all over the world, who come to pay homage to a young woman named Morfydd Owen.

A Welsh mezzo-soprano, musician, and composer, Morfydd died aged just twenty-six.

Supremely talented, she began composing as a young child, and on her passing, left a legacy of some two-hundred-and-fifty scores.

Whilst studying at the Royal Academy of Music, she met Dr Ernest Jones, a psychoanalyst of the Freud school, and within three months they were wed.

Unfortunately, the pressures of being a new wife took their toll upon Morfydd, not helped by Ernest’s insistence that she manage his professional and social calendars, to the detriment of her own career.

But it was when Morfydd was struck with appendicitis, in September 1918, that things took an odd turn.

Though the hospital was barely any distance away, she was operated on at home.

Her death was said to be due to delayed chloroform poisoning, though no autopsy took place, and she was buried two weeks before her death certificate had been issued.

And her memorial – a stark sandstone column – bore her incorrect date of birth, her wedding date (which was a very uncommon addition), and an engraving taken from Goethe’s Faust: ‘Das Unbeschreibliche, hier ist’s getan,’ which translates as, ‘Here the indescribable has been done/accomplished.’

Hmm? Maybe Ernest just wasn’t the sentimental type. (And he did bounce back, just one year later – Cyparissus, take note – marrying for a second time. Well, I suppose those calendars aren’t going to organise themselves.)

Historic tragedies

We learned about lead-lined ‘chest tombs,’ where handily marked entrance slabs could be removed, to reveal snaking staircases, leading down to stone shelves where the bodies were laid.

We saw memorials to the local lifeboat men who perished in three historic tragedies, and it was terribly touching, looking down on those, still neat and tended graves, whilst Bev described the particulars of each maritime disaster.

On a brighter note, we met William Bancroft (nicknamed ‘Billy the Whizz’), a Welsh rugby international and Glamorgan County cricketer, who was memorably described in a newspaper article of the time as, ‘ten stones of fencing wire, fitted with the electricity of life.’

There was Harry Parr-Davies, a child prodigy who, as well as writing scores for musicals, collaborated with Gracie Fields, and was her preferred accompanist.

‘Wish me Luck as you Wave Me Goodbye’ was one of his, and during the war, when he enlisted in the Irish guards, Gracie refused to entertain the troops unless Harry was seconded to ENSA (Entertainments National Service Association).

And, as you’d expect, Gracie got her way.

Glass lid

And then we visited the largest tomb in the cemetery, belonging to the colourful Folland family. By all accounts, Henry Folland, was a topping fellow.

From humble beginnings, he grew up to be a skilled statistician, eventually working his way from a lowly clerk to become company chairman of the largest tinplate factory in Europe.

A keen Egyptophile, he died in 1926, whilst holidaying in Cairo, and it took over four weeks to repatriate his body. You can probably imagine how he must have looked after a month at sea.

But if you’d been around back then, you could actually have seen for yourself because, for some unfathomable reason, Henry’s coffin of choice was a glass-lidded affair.

However, putting that image aside, a more palatable one was conjured by Bev’s anecdote about Henry’s adored Arabian stallion.

Every evening, the beautiful white horse would trot through the cemetery, just so he and his rider, could pay their respects to a master who was, obviously, very well-loved.

Returning to nature

Next, after pausing at the unmarked paupers’ graves, forgotten by most, excepting Bev, who is passionate about researching these poor unfortunates, we wended our way up to the carbon-neutral Woodland Burial Area.

A recent addition to the cemetery, here mature trees are complimented by new plantings, and you can be laid to rest, content in the knowledge that you are returning to nature, whilst helping to preserve a beautiful woodland.

You don’t even need a coffin – a shroud is acceptable.

Plus, if you fancy giving your family a bit of a pre-funeral work-out, you can even specify that they dig your grave, which is both a lovely idea, and pretty funny; I could just see Tim sweating over his shovel, and ruing the day he’d ever met me. Lol!

Faith

And then it was a gentle stroll, back to the sad cypress, passing graves of numerous faiths that share this land.

Bev explained Swansea’s cosmopolitan approach to interment, and it was genuinely heartening to see that, not only in life, but death too, religious diversity is celebrated and embraced; though the Plosker Memorial Gates of the Hebrew cemetery provided a profoundly poignant reminder of an era that was not so tolerant.

It was a weird, but rather wonderful, afternoon. We’d all enjoyed our symbolic scavenger hunt, and reading the inscriptions gave candid insights into the social history of our city, and people.

Whether that was told by stone angels, marble crosses, or through the absence of all such trappings, when Bev said that: ‘Everyone here has a tale to tell,’ she certainly wasn’t wrong.

Bev runs a variety of tours, walks and courses throughout the year, so if you’re interested in learning more about the history and folklore of our local areas, you can reach her via her Facebook page, Swansea and Gower Lore, or visit her website for details of upcoming events.

And I should mention that I have left out A LOT of what her tour covered – not just because this article would be five times as long, but also because I don’t want to give away all of her research secrets.

So, if you want the full picture, send Bev a message, and prepare to be wowed.

Catch up on Del’s other adventures here

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

That was a good read Del…

Another entertaining article Del full of interesting historical information. Looking forward to reading your next article.

Great read Del. Didn’t realise that cemeteries ( or is it graveyards ) could be so interesting.

What a fascinating read Del, really interesting and Bev is clearly and enthusiastic expert.

Del that was a really interesting read and great that they have Bev there with her historical information !

I look forward to your next article they are so diverse , they are brilliant!