Dragons in Dungeons: Rehabilitating the Welsh Historical Romance

Adam Pearce, Editor, Melin Bapur

Like the history of any nation, for many the study of Welsh history is synonymous with the story of its heroes, chief among them Llywelyn Fawr, his grandson Llywelyn ein Llyw Olaf and above all Owain Glyndŵr.

These figures have always fascinated us and continue to do so, and whilst a big budget Hollywood version still eludes us, their stories are constantly being adapted and retold for new audiences in documentaries, plays and of course in novels, perhaps most famously John Cowper Powys’s Owen Glendower.

These adaptations are nothing new, and in fact these stories have always been told and retold since they first happened.

But here in Wales we’re not always the best at remembering that, and it’s telling that it will come as a surprise to many to learn that Cowper Powys’s novel, for example, was not the first novelistic adaptation of the Glyndŵr story – nor even the second or third.

In fact Glyndŵr alone was the subject of no fewer than four novels written in Welsh in the nineteenth century – and that’s assuming there aren’t more that I haven’t found yet.

In some ways it should be no surprise at all that the late Victorian age would be something of a golden age for the historical romance in Wales: after all, it was a period of Welsh national reawakening, and the world’s most popular author that century was Walter Scott, who had invented the historical romance with works like Ivanhoe, Waverley, Rob Roy and the like.

These kind of national romances are, in a way, exactly what you might expect Welsh novelists to have produced at the time – and they did, in copious quantities.

Sadly these stories are now almost completely unknown, and it must be admitted that the quality is extremely uneven; but if there is a genre and period in Welsh literature that is ripe for reassessment it is this one.

“Great fun”

The first of these started appearing in the 1860s, almost at the birth of the Welsh language novel (Gwilym Hiraethog’s Aelwyd F’Ewythr Robert, which might reasonably be considered the first, had appeared in 1852) and some time before Wales’s first truly great novelist, Daniel Owen, began writing his own masterpieces.

They really picked up however in the 1870s and 80s, which saw the publication of works like Llywelyn Llyw Olaf Gwalia (anonymous; 1872-3) Karl y Llew (anonymous; 1875-6), Ednyfed Fychan by Thomas John Jones (1878), and Owain Glyndŵr by John Davies Jones (1877-8), all of which appeared in magazines and newspapers; and Gruffydd ab Cynan (1885) by Elis o’r Nant. This is just a tiny selection; there are literally dozens.

By the 1890s there had been at least one example by a woman: Mary Oliver Jones’s Y Fun o Eithinfynydd (1893), which follows the romantic exploits of the poet Dafydd ap Gwilym.

Typically, these works are historical only in the sense that their characters and plots vaguely match a few basic historical facts: the real-life events are nothing more than a loose framework on which the author hangs a swashbuckling adventure (often too poorly constructed plot-wise, jerking from one fight to the next, to provide much real excitement).

One of the earlier, and better examples of this kind of ‘boys’ own’ adventure is Isaac Foulkes’s Rheinallt ap Gruffydd (1873), which benefits from being very short, making the loose plot is less of a problem.

It was also one of comparatively few of these works which was published as a book, rather than just a serial. Its historical material is scanty – a half remembered minor skirmish in Chester during the Wars of the Roses which led to the Mayor of Chester being hung by a Welsh nobleman – giving the author plenty of room to make up some exciting backstory and flesh it out with side creative side-characters who are far more fun than the straight-laced eponymous hero.

Great fun, and fairly undemanding content-wise: one can imagine this is the sort of thing the likes of Roger Edwards were reacting to when they complained about the perils of frivolous fiction.

Ambitious works

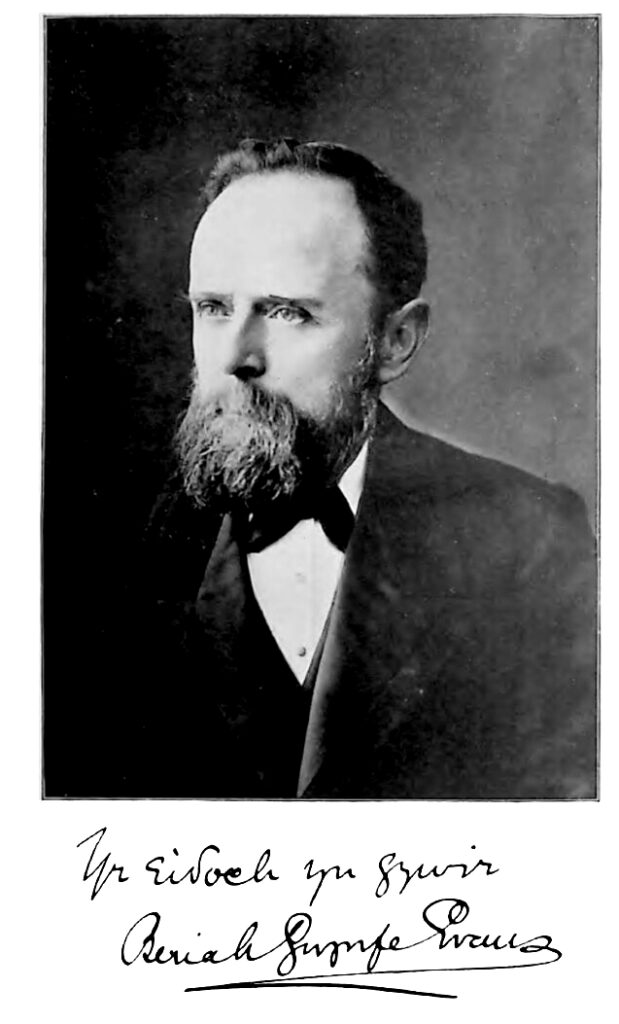

By the 1880s, the authors were getting more both ambitious and more historically informed, and perhaps the best, and one of the most prolific, of these authors was Beriah Gwynfe Evans (1848-1927), who published around a dozen novels in both Welsh and English, of which more than half are historical romances.

His first novel, Bronwen, the Welsh version of which (1880) is subtitled Chwedl Hanesyddol am Owain Glyndŵr (a historical legend of Owain Glyndŵr) is a typical example of Beriah’s (call your child ‘Beriah Evans’ and you destine them be a first name forever!) work in the genre.

Alongside an appropriately creative reinterpretation of both the history and also some of the more doubtful legends surrounding Glyndŵr, after a somewhat slow start (the book has a Foreword, an Introduction, and a Prologue before the first chapter) Beriah finds plenty of room to cram in a smorgasbord of romantic cliches: a fair maiden (with overflowing bosom), love at first sight (forbidden by the parents, of course), the throwing down of gauntlets, a hero disguised as a pedlar, a bandit with a heart of gold, scheming villains, swordfights, a black knight with a hidden identity, an escape through a secret passage, even a bar room brawl.

You’ll already know from reading that list whether this is the kind of book you’ll enjoy or not. At one point the poet Iolo Goch makes a prophecy, and a thunderbolt obligingly rends the sky.

It all sounds ridiculous, and it absolutely is, but that doesn’t take one jot away from just what tremendous fun this novel is.

It is also, in its own way, quite daring, and those whose assumptions about Welsh books from this period are stiffly-starched chapel-white will be amazed to hear that at one point a character is thrown from the battlements of a castle and splatters his brains all over the King of England. An argument over seiat membership this is not.

Sowing seeds

As I mentioned, Beriah wrote in English as well as Welsh, and some novels, like Bronwen, exist in versions in both languages (though we have published the Welsh).

As he noted in his introduction Beriah was conscious of a need to educate the Welsh about the history of their own country, and clearly wished to extend this to the growing proportion which could not read Welsh.

A few of his novels appeared in English only, one of which was 1885’s Llywelyn, first of a two-parter about Llywelyn ein Llyw Olaf, the last of the Native princes.

The language, the historical period and the Prince of Wales may be different, but the tone and style is very much the same, if perhaps a little less fantastical, and perhaps its pacing a little jauntier.

This time the plot finds space for shipwrecks, jousts, and a prison break from a dungeon, and the main villain being a Welshman – Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn, here in his classic full pre-revisionist bare-faced traitor role – provides an extra dimension of interest.

It gives the non Welsh-speaker a chance to sample the style in full, and further evidence, if it were needed, that no, Caradoc Evans did not invent Welsh Writing in English. Great stuff.

Of the two novels, personally I prefer Bronwen for being the more gloriously bonkers, and because Beriah’s dialogue in Welsh is better than his pseudo-Shakespearian English dialogue.

But really there is not much to pick between the two: one gets the sense that Beriah was picking his Historical to fit the formula, and that perhaps touches on the obvious weakness of the genre as a whole.

As Dafydd Jenkins observed in his 1944 essay on the Welsh novel, to a certain extent these novels are all the same story: whether the hero is Llywelyn, Glyndŵr, Rheinallt ap Gruffydd or some fictional lieutenant, he will be always be perfectly noble, chivalrous, and Welsh; the women all fall into the mother/crone/maiden categories, the latter invariably pure, docile and virtuous, their main contribution being to faint at the appropriate points (Bronwen is, to be fair, given the occasional witty rejoinder too, and even the opportunity to help out the hero once or twice).

Equally predictably, the inevitable scumbag of a dastardly villain will be perfidious, almost impossibly sadistic, and often (though not always) English.

The hero will be challenged, the maiden imperilled, the hero will overcome, the villain will be defeated, and the heroes ride off into the sunset, history be damned (the plot of Bronwen ends with Glyndŵr crowned Prince of Wales; the eventual defeat of his rebellion a few years later is glossed over in a few pages of afterword).

Although this kind of thing makes the stories absolutely of their time and generally rather predictable, from a historical perspective it is fascinating.

Growing patriotism

Clearly writing this sort of thing – just as was done in poetry by the likes of Eben Fardd – served as a socially acceptable outlet for Welsh patriotism in the Victorian British context.

In these stories, the Welsh, and Wales itself in a sense, get to be the heroes.

Whilst the historical distance between the period these novels portray and that in which they were written ensured that there was little danger of their being interpreted as calling for the kind of violent national struggle that they actually depict, and in their own way it’s possible to view these books as a kind of nationalist resistance, demanding, as they do, acknowledgement of Wales and its history as a valid subject for grand, heroic narratives.

Furthermore, by setting these stories in the middle ages the English could be the villains for once, and indeed they are frequently lampooned or condemned as cruel and vicious (though equally often the authors are at pains to show noble examples).

Alternatively, casting a Welsh traitor as a villain – as in Llywelyn – invokes the old trope that the Welsh could win, if only they could stop fighting themselves.

Whilst these books may in some sense be about the past, they were very much writing for the present; paradoxical as it may seem these are not backward-looking works, but ones actively seeking to re-forge a vision of Welsh identity in the time in which they were written.

This is a very clear and deliberate dimension of these works, and one which may appeal to some readers today in a way the more established works of the Welsh literary canon might not.

They were, indeed, of their own time, and destined to remain so.

By the 1900s Welsh Historical Romances had begun appearing markedly less frequently, probably because the particular flavour of nationalist fervour that had inspired them had fizzled out with the failure of the Cymru Fydd movement.

In the twentieth century, the acute awareness of linguistic decline which pervades much Welsh literature, not to mention the horrors of war and genocide which so profoundly influenced all aspects of human creativity in Wales as everywhere else, made such works impossible.

Novels in Welsh with echoes of Bronwen do still appear; however, they tend to be framed explicitly as stories for younger readers (Elizabeth Watkin-Jones’s Luned Bengoch (1946) for example), and eventually, by the 1960s, novelists like Rhiannon Davies Jones and Marion Eames would start writing a more nuanced and complex kind of historical novel in Welsh, novels which owe almost nothing to the Historical Romance.

And yet, the sheer number of Historical Romances which appeared in nineteenth century Wales testifies to their popularity with readers; and the rapidity with which they were almost entirely forgotten is striking.

It seems likely that, as I write this, perhaps only a tiny handful of people alive have read Bronwen, or even know it exists.

One suspects perhaps they were just the wrong sort of story: too violent, and not ‘improving’ enough for the nonconformist mainstream; and at the same time too obviously romantic, too clearly intended to entertain, and thus insufficiently literary for the young lions of the Welsh universities.

They weren’t entirely wrong: the 19th century in Welsh literature is infamous for producing a very few diamonds in a vast ocean of rough, and in honestly most of the Historical Romances probably deserve their obscurity.

And yet the best of them, like those of Beriah Gwynfe Evans, surely deserve to be given at least a chance, and an opportunity to see if the perspective of the twenty-first century might look on them more kindly than the twentieth century did.

A version of this article can be read in Welsh on www.melinbapur.cymru.

Rheinallt ap Gruffydd by Isaac Foulkes (£8.99+P&P), Bronwen (£12.99+P&P) and Llywelyn (£11.99+P&P) by Beriah Gwynfe Evans are all available now from www.melinbapur.cymru and from all good Welsh bookshops.

Also released from Melin Bapur this week is Woyzeck (£7.99+P&P), a new Welsh translation of the German play by Georg Büchner.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.