I Fought the Law, dramatic licence and double jeopardy

Dr Huw Evans

Dramatic licence can justify ‘good TV’ but accuracy is important. This article looks at the recent ITV drama I Fought the Law in a broader and more dispassionate context.

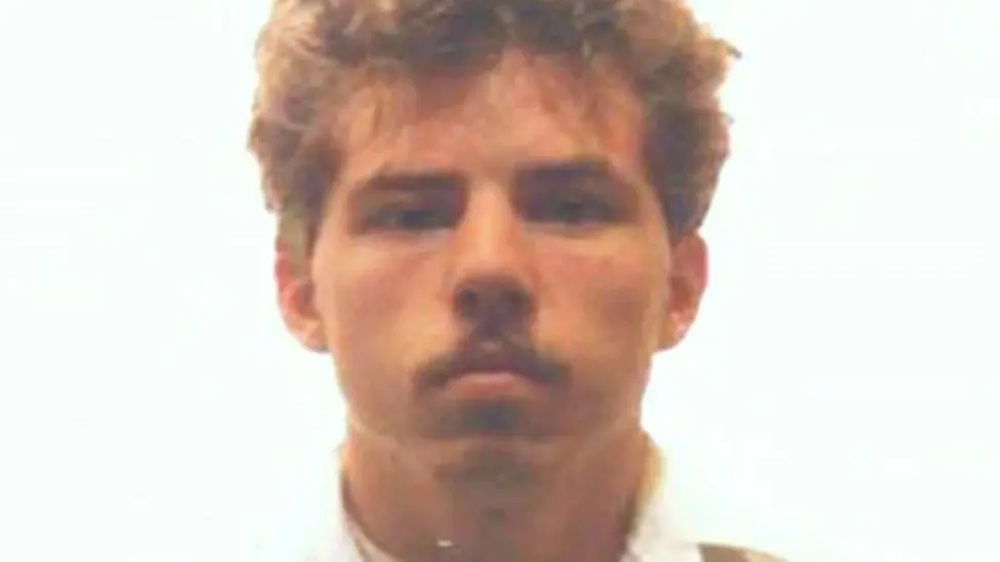

The Drama is about Ann Ming’s fight to change the law to enable a retrial after William Dunlop was acquitted of the murder of her daughter, Julie Hogg.

Because of the ‘double jeopardy rule’ this was not originally possible.

With the help of Ming’s efforts, the law was changed by the Criminal Justice Act 2003 (2003 Act) and Dunlop was retried. This time he was convicted, and he was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Inevitably with such a TV production, the focus is not on the wider context or with the detail of related issues. This article discusses those other aspects. It falls into three parts: the rationale for the double jeopardy rule; reasons for the law change; and the practical effect of the change

Rationale

The double jeopardy rule means that a person found not guilty of a crime cannot be tried again for the same crime. In England and Wales, the rule is part of the common law and is long established. Similar law is found elsewhere such as in the USA: the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution states that no person shall ‘be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb’.

There is sound justification for the rule: to prevent oppressive conduct by the repeated attempts of one person to prosecute someone else for a crime until a conviction is obtained. There is a public interest in stopping this behaviour. A prosecutor can be a public prosecutor like the Crown Prosecution Service or the Health and Safety Executive but, because private prosecutions are permitted in England and Wales, a prosecutor can also be a charitable body (like the RSPCA) or a Corporation (like Sky TV) or a private individual.

The rationale for the double jeopardy rule was not obviously present in the drama. In fact, the impression conveyed was that it was an historic anomaly that stood generally in the way of justice.

Reason for change

While there is justifiable rationale for the rule as a general principle, sometimes its blanket application might not be justified: for example, where there is a serious offence such as murder and compelling new evidence becomes available after the original acquittal. This is what happened in the Dunlop case. He was acquitted of murder, but compelling new evidence emerged as he later admitted the crime.

The drama’s focus was on Ann Ming, but her campaign was part of a wider unacknowledged movement for law change.

The explanatory notes to the 2003 Act mention that the law change was developed from 2001 Law Commission proposals and the 2001 Criminal Courts Review of Auld LJ. But while the Dunlop case undoubtedly had a major influence there were other contributors to the change. By way of illustration two are mentioned: the Stephen Lawrence case and DNA evidence advancement.

Stephen Lawrence was murdered in 1993. Following concern over police inaction, a private prosecution was brought by the Lawrence family against Gary Dobson, Neil Acourt and Luke Knight in 1996, but they were acquitted. Following the Stephen Lawrence enquiry conducted by Sir William McPherson, he recommended: ‘That consideration should be given to the Court of Appeal being given power to permit prosecution after acquittal where fresh and viable evidence is presented’. And following the law change, Gary Dobson was retried and convicted.

As to DNA advancement, the potential evidential reach of prosecutors has been substantially enhanced because of scientific developments; and unsolved cases have been reopened and resolved because of new (and previously unavailable) evidence. Jeffrey Gafoor’s murder of Lynette White is a well-documented Welsh example.

In these new circumstances there was a very real possibility that DNA evidence would emerge in cases implicating a person previously acquitted. This was a significant catalyst to the law change. The conviction of Dennis McGrory in 2022 is an example of a retrial in these circumstances; he was originally acquitted in 1976 but DNA evidence implicating McCrory was obtained decades later.

There are competing public interests: first, in the prevention of harassment through continued prosecution; second, that someone should normally be prosecuted for a crime where there is evidence. There is a balancing act to be struck between the two. As a result of the change, the double jeopardy rule continues to usually apply but exceptionally it will not, and there will be a retrial.

Effect of change

Following the law change there are strict criteria that must apply before any retrial. It can only occur if the offence is listed in the 2003 Act; essentially any offence listed carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. This includes murder, manslaughter or rape but not, for example, theft. The permission of the Director of Public Prosecutions and the Court of Appeal must be obtained.

Each must be satisfied that there is new compelling evidence. Additionally, for it to proceed, the DPP must be satisfied that is it is in the public interest and the Court of Appeal satisfied that it is in the interests of justice. It is a high bar.

Unsurprisingly, there have been few cases which have gone to retrial. Usually, the double jeopardy rule continues to apply but there are limited exceptions in the circumstances described above.

The drama was enjoyable and recorded Ann Ming’s pursuit of justice for her daughter. It is important though to look at the law change in a broader context.

The double jeopardy rule is not a relic of history. It has a sound justification, and it has continuing relevance. Yes, it can now be disapplied but only in very limited circumstances. Ann Ming’s campaign contributed to that change, but it was not a solo effort.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Such an interesting article which demonstrates how dramatic license can skew the facts and misrepresent the law. Huw is so good at shining a light onto lesser known aspects of the law, and doing it in a way that’s both clear and engaging!