‘I must not let it go’: Yale Review editor shares what happened when he began to speak Welsh

Stephen Price

A Senior Editor at the Yale Review, the oldest literary journal in the United States, has shared his experience of learning Welsh to reconnect with his mother’s side of the family.

Dan Fox is the former editor of Frieze magazine and author of Pretentiousness: Why It Matters and Limbo, and codirector of the film Other, Like Me: The Oral History of COUM Transmissions and Throbbing Gristle.

Before joining the Yale Review – the renowned journal of literature and ideas – Fox, who grew up in southern England before building a life and career in London and then the United States.

In his touching essay, What Happened When I Began to Speak Welsh which was published recently, Fox begins by sharing an account of his maternal grandmother’s death twenty years ago, and her funeral in a small Methodist chapel in the Conwy Valley.

He shares: “The funeral was conducted in Welsh. It was my grandmother’s first language. Mum’s too. I didn’t understand a word. I followed the congregation when they stood to sing and sat to pray, but my grief remained isolated in English and the music of sniffly noses and creaky pews.

“Near the end of the service came a hymn. I recognized the melody, “Cwm Rhondda” (“coom ronda”), so rousing and anthemic that Welsh rugby fans belt it out from the terraces before big matches. At the end of each verse, the lines repeat, step higher, and split into harmonies—everyone knows how these go, tenors climbing on baritones, sopranos atop altos. At its peak, the melody slows dramatically, voices at full power, before making a stately descent to its resolving chord.

“I knew the tune well enough to hum along. The air seemed to tremble in that small and intimate room. I heard myself embedded in the chorus, but outside the language. In the final soaring bars of the hymn, I looked at my grandmother’s little coffin resting in the aisle, and something between a thought and a sensation ran through me: I am part of her language. I must not let it go.”

Fox described how there were touches of Welsh throughout his childhood, such as ‘Nain’ and ‘Taid’ – the north Walian Welsh for gran and grandfather, but says he didn’t need more, since both grandparents could speak English, and I grew up in the South of England, where almost nobody knew Welsh.

Fox’s mum left Wales in the 1960s, shortly after his brothers were born, moving first to Canada, then back to Britain after the end of a short-lived marriage. In search of work, she landed in Oxford, where she met his father, who came from an Irish Catholic family in the North of England.

He writes touchingly: “When I was a baby, Mum sang Welsh lullabies. Heno, heno, hen blant bach (tonight, tonight, little children). Occasionally, Welsh words became family slang—“I’m going to the cyfleusterau [“kuh-vluh-ste-rai”],” meaning “conveniences, bathroom”—but we always spoke English.

His feelings and awareness of Welsh heritage remained strong, as he says: “I often heard English people dismiss Welsh as a jumble of consonants, a nuisance to tourists, a dying language. I took the insults personally, feeling protective of Mum and the family, like a guard stationed outside castle walls, loyal to the life inside. Growing up in England with a Southern accent, I was different from my Welsh cousins, but I seldom thought about why I couldn’t speak their language.”

With a large US and worldwide readership, Fox encouragingly gave some Welsh history to his readers, before detailing how: “In 1847, an infamous government report on education in Wales blamed the “evil effects” of the Welsh language for indolence, illiteracy, and violence. As a consequence of the report, English was aggressively pushed in schools, putting Wales on an expansive path of bilingualism. When Nain was a girl, children caught speaking Welsh at her school were made to wear a wooden paddle around their necks—the so-called Welsh Not. The last one tagged with the Not at the end of the week was beaten.

“Welsh was cast as subaltern, the impediment to prosperity; English became the tongue of modernity and opportunity, spread through laws, commerce, and quiet acceptance. By 1911, when Nain was two, only 43 percent of the country spoke Welsh. By Mum’s infancy in the late 1930s, that number had sunk to almost 30 percent, and in the 1960s, when she left the country, it was down to a quarter of the population. What Welsh remained was concentrated in the rural North.”

After discussing his visits to north Wales as a child, he shared how when he hit his late teens, Welsh was less on the agenda, and he began to visit less, instead turning his attention to London.

Work then took him to New York, where he says he lived surrounded by immigrants who spoke two languages, or four, and he was only a monoglot. Americans, he noted, liked to index their ancestry. He would explain that his mother was Welsh-speaking but nobody he met in New York had ever heard it spoken.

As time passed by, however, he “had the vague sense” that he was neglecting something. That “something” could not be satisfied by bara brith, or by heavy Welsh blankets.

He writes: “It was inside the Welsh language itself. One day I’ll learn it, I told myself, and I will understand the message carried in the memory. I’ll start tomorrow, maybe next week.”

Like many, Fox’s impetus to change began in 2020 during the arrival of the pandemic – his tenth year in New York.

He writes how, on his last visit, only months earlier, he had watched his mum shuffle old photographs from a wrinkled envelope, her fingers thick with arthritis, and spread them on the cheerful oilcloth that covered the kitchen table. They spoke often about the photos taken at a place called Tal-y-Braich Uchaf , perched on a remote ridge in the Eryri mountains, where the family of nine lived in three bedrooms.

He writes: “The house was lit by oil lamps. They kept food cold in the stream outside. Taid tended his sheep on the slopes, and sometimes the children would summon him in for meals with blasts from a conch shell.”

Unable to travel, and “liberated by lockdown”, he found himself online, and casually downloaded Duolingo, selected “Welsh,” and played the first quiz.

He writes: “The pleasure was immediate. Familiar sounds crystallized into verbs and nouns, as if there were some base material of Welsh already within me.

“How slow—embarrassingly slow for a writer—I had been to see that Mum’s language was a portable inheritance. If I learned Welsh, I could take it with me anywhere: it weighed nothing, yet it held my family, and so much else, inside.

“I walked around my apartment repeating fragments of tourist Welsh. “Dw i Dan” (I am Dan). “Dw i’n byw yn Efrog Newydd” (I live in New York). Efrog Newydd! There was a translation nobody needed, but what a beautiful sound. I thought of Mum. I thought of a story she had told me about having to walk for miles along the empty roads between Tal-y-Braich and school. One day, she said, she decided to bring a pocket mirror and hold it in front of her as she walked so she could see the reverse view. I asked why. For a change of perspective, she said.

Giving further context to some of Wales’ biggest grievances against England, such as Tryweryn and deindustrialisation that devastated the country in the 1980s, he shared how even as a child, he sensed the sadness.

“Reputation for difficulty”

According to Fox, Welsh has a reputation for difficulty, but thanks to his mum, in my first weeks on Duolingo, he had no fear of consonant gridlock.

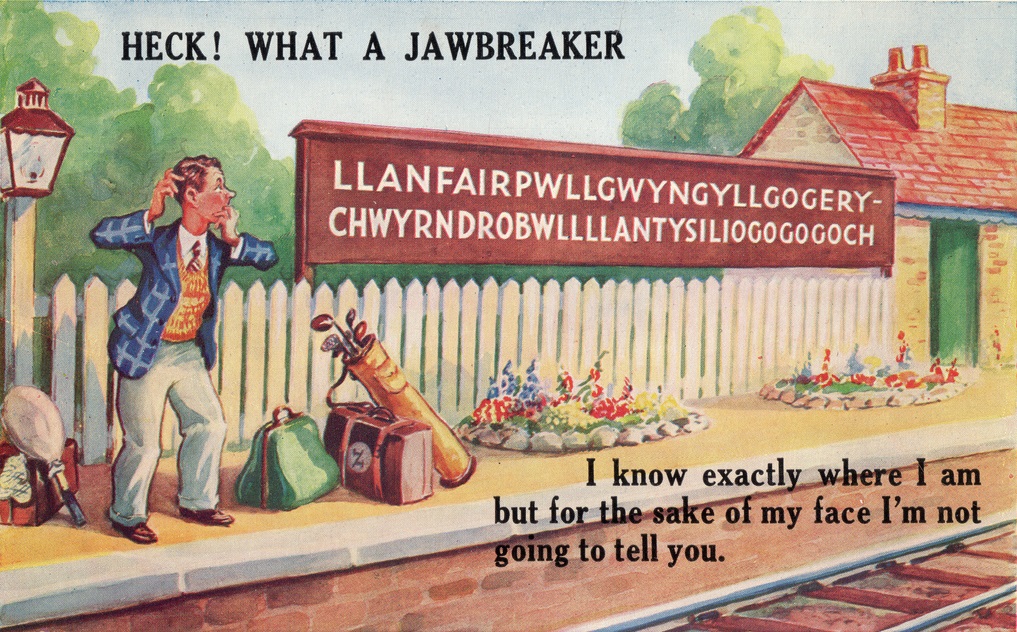

He writes: “There is a YouTube clip of the stand-up comic Rhod Gilbert, an Anglophone Welshman, describing the fate of his classmates in a thirty-person Welsh course: “One passed, three failed, and twenty-six dead.” I could believe it.

A year after the pandemic began, he made his first visit back to Oxford, but his mum found a few holes in the Duolingo take on Welsh learning, leading him to feel “like a sucker for putting my faith in an app, as if I had done something disrespectful”.

Back to New York, he resolved to take his lessons seriously but struggled to find in-person Welsh classes.

He writes: “When I tried the Amikumu app, designed to locate nearby speakers of a given language, the closest Welsh speaker was in Philadelphia. I attended a meeting of the New York Welsh—a friendly group that meets regularly at a bar in Midtown—but everyone I met was an Anglophone from South Wales.”

However, he shares, music helped. He writes: “On the internet radio station NTS, I found the Casgliad Cymru (Welsh Collection) and went deep into a playlist for the post-punk label Ankst. I could pick out the odd word, but I was mostly content to let Welsh wash over me as it did in childhood.

“I liked Gruff Rhys’s gentle psychedelia. He grew up near Nain and Taid’s farmhouse and sang in a crisp Welsh that reminded me of people who would pop in to visit Nain. Running his song titles through Google Translate felt like cheating—and it was unreliable for Welsh—but I let myself use it to collect scraps of vocabulary. In a plaintive song by Kelly Lee Owens and John Cale, “Corner of My Sky,” I listened to Cale intone the phrase Dechrau yn y Gogledd: Start in the North.”

Around this time, Fox stumbled upon an online trial lesson in Welsh offered by the company SaySomethingin.

Its mission to “reverse the language shift in Wales, through the development of a totally original language learning methodology,” had an appealing nerdery, he shares, writing: “This methodology promised to teach me a sentence in just one week. The approach is simple: the teacher provides a phrase in English, the student repeats it in Welsh; the teacher adds a few words to the phrase, the student follows suit. Eventually you arrive at a complete sentence.

“One quiet afternoon at home, I signed up and started the first thirty-five-minute lesson. Aran, my instructor and one of the company’s founders, cracked dad jokes and gave dorky pep talks I grew to appreciate. A busy online forum made it easy to ask questions—and provided the sense that the system was run by Welsh teachers, not start-up bros. I can still remember the sentence from that first week: Dwi isio dysgu siarad Cymraeg achos dwi’n caru Cymru a dwi isio yr iaith Gymraeg barhau (I want to learn to speak Welsh because I love Wales and I want the Welsh language to continue). A mutation of parhau, the word barhau (“bar-high”) means “to continue.” It can also mean to persist, endure, survive. This was not Duolingo’s potatoes-or-chocolate Wales.”

Detailing some of the course at the beginning, he shared: “For the first twenty-five lessons of the course, I did not learn a single number, or how to ask directions to the railway station. I was drilled in metastatements about learning Welsh, such as “I want to speak Welsh with you” and “I still need to practice more.” The system didn’t explain the rules of mutations; it advised internalizing them through practice.

“As new vocabulary cemented rapidly, the sentences developed into mind-bending strings of social relationships: “I met someone in the pub last night who told me that she wants to speak Welsh with you,” for instance, or “I met an old woman in the pub last night who told me that she knows a young man who works with your sister.”

“This felt real. It was how I had first heard Welsh: gossip at Auntie Gwenda’s house, news in Nain’s kitchen. At home, I hammed up the North Wales cadences, enjoying how the accent rolled from my mouth. I sounded like my family.”

So has he sailed into fluency, reciting cynghanedd poems to his mum on FaceTime? The truth, he says, is more complex.

He shares: “There is a paradox to my efforts: I am learning Welsh to speak to my family and make it always alive, in the room with me, as it was in childhood, yet I often shy away from the opportunity to speak. In the presence of my aunties and uncles, and even with Mum, the sounds clog in my mouth, and I become suddenly doubtful and halting. I retreat into English.”

When he last returned to New York, however he shared his most recent goodbye with his mum at the airport.

He writes: “Mum held my hands and said something I couldn’t quite understand—it was long, I was crying, I could pick out only fragments.

“It didn’t matter. We were speaking Welsh.”

Read Dan Fox’s article in full here.

Click here to find out more about SaySomethingInWelsh.

Click here for more info on DuoLingo.

Click here for information on local Wales-based Welsh classes or London classes (Not exhaustive so please check social media and search engines for what’s on in your area)

Click here to find out more about Lingo Newydd.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Stori hyfryd. Diolch!

Very interesting but Rhondda should not be pronounced as “ronda”. The double “dd” should sound like the “th” in words such as “though, there, them, the, this” etc. but not sound like the “th” in “three, theory, thanks, think, thought” etc.