Iaith Pawb?

Huw Williams

Glaw yn disgyn, Dagrau o Aur; Sŵn tywyllwch, A dawns y dail.

Mae’r Ysgol fechan heb ei chan, Tegannau pren yn ddeilchion man,

A’r plant yn gadael am y dre. A’r plant yn gadael am y dre.

Dewi Pws’s image of the empty village school in his song, Nwy yn y Nen, is a poignant one for those brought up in rural Wales. There is nothing more emblematic of communities dying on their feet, of the slow untwining of the tapestry of village life. In many parts of Wales, it can often mean another nail in the coffin of Welsh as a community language.

One of the more recent, indicative examples, was the primary school in Abersoch. The sealing of its fate signalled the destructive correlation between economic heft and Welsh language decline: in this case it is primarily the so-called Cheshire Set who have used their capital to buy up properties in the most Welsh-speaking region of Wales, turning it into an English language enclave not unlike those on another peninsula, facing the Mediterranean.

Retreat

The rest of Pen Llŷn, one of the last bastions of Welsh as a majority language, is not immune of course, and indeed it has been a long retreat with respect to village schools. My own father’s first academic post was on a project looking at school closures in the area in the mid-70s (where he met Carl Clowes, who was at that time leading the establishment of Antur Aelhaearn).

My Dad’s own village school in Llwyncelyn, where his father was headmaster, closed in 2011, and that was as part of a series of cuts in the south of Ceredigion that has seen area schools established. That programme eventually reached the north of the county and the home village of my grandfather, in Borth. As a number of news stories detail, four village schools in total in the north of the county have come under threat.

It has been a process mired in controversy, where the solution this time was not new area schools but amalgamation and the busing of children from one village to another (a not insignificant difference with the south of the county, one who is sensitive to intra-Ceredigion politics might note). However, these communities are fighting on and in April this year they were granted what has been described in The Cambrian News as a ‘stay of execution’.

Borth

Observing from afar (Grangetown, Cardiff to be exact) and as a boy brought up down the road from Borth in God’s own Country (Dole, to be even more exact), I am minded to reflect on the nature of Borth as a community in the context of these plans. There still remains there 40% of the population who can speak Welsh (which may come as a surprise to those who know something of the village) and this is no doubt thanks to the school, in no small measure.

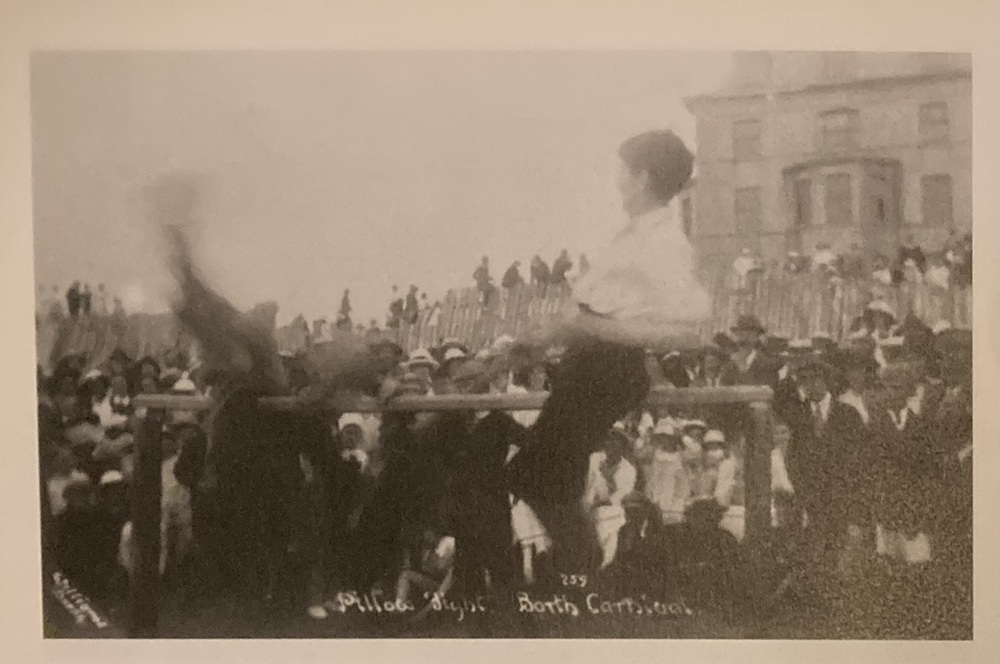

I suggest it might surprise some because language shift happened in this coastal tourist village comparatively early. Family folklore has it that it shifted even within the same generation: my Great Uncle Vic, the youngest of the siblings, was said to speak a fair amount less Welsh than his brothers and sister, partly on account of the evacuee population that landed during the war.

Whether or not this story reflects the reality of things, it does not obscure the fact that – as with many villages on the train line that reaches into mid-west Wales from the English midlands – it has been historically more Anglicized than many of the neighbouring villages in the hinterland. Those who have settled there have also come from more diverse socio-economic backgrounds than Abersoch’s Cheshire Set, with working class families from the Black Country laying down their roots there.

And then there’s the school itself, where the vast majority of the children come from English-speaking homes, with a high percentage of children registered as having Additional Learning Needs. They face being uprooted and bused to Talybont, a village with a different demographic and famously home to the Welsh-language publishing house, Y Lolfa.

Welsh-medium sanctuary

There is no doubt among the parents whom I know how important this Welsh-medium sanctuary is for the children, the community and the language in the village. It is very difficult not to feel that this is the bureaucratic logic of austerity becoming an end in itself, intersecting with implicit assumptions about which communities merit their own schools, and which do not (Angharad Dafis tells the salutary tale of this use and abuse of numbers in the story of Ysgol Felindre, deemed surplus to the requirements of its community by Swansea Council, in the thrall of (suspect) figures).

Now if you visit Borth these days you will notice a most recent addition to its topography on the beach, and out in the bay. There lie huge boulders brought in to support the sea wall against the encroaching tide. The sea has long been lapping at the village gates; in the old family home on the seafront – so the story goes – they would open both the back door and the front to allow the seawater to wash through into the street. But now the threat to the village of being squeezed between the sea and the Afon Leri, and joining the ancient kingdom of Cartre’r Gwaelod, is a very real one.

A cynic might question the logic of spending millions on sea defence, only for the council authority to later decide it would hasten the demise of the village as a living, breathing community by getting rid of its vital organ. It does not take much imagination to picture Borth becoming a glorified holiday village that would eventually go the same way as Fairbourne, further up the coast. The community deserve better. Maen nhw’n haeddu gwell.

My own place in this narrative is a little tangential, having migrated with so many from my square mile down to the capital city. The question of who merits Welsh-medium schools, however, is painfully relevant, closer to what has been my home for 15 years.

I have told the story before in some of its grim detail, but in a nutshell, three years after moving to Grangetown I become embroiled in a campaign (where I coincidentally collaborated with Carl Clowes’ son, Cian, among others) for a Welsh-medium school for the ward and its neighbouring community, Butetown. It was a school promised by central government, included by then-Education Minister Leighton Andrews in the 21st century schools programme.

Longevity

The local Labour councillors were hell-bent on stopping this for various prejudicial reasons – reasons I got to hear first-hand at local branch meetings as a then-member of the party. They could certainly not be accused of being short-sighted on the matter. One the contrary, one of their apparent fears was that such a school would embed a Welsh-language community that would eventually vote them out (Lynda Thorne and company were clearly confident about their longevity, and apparently didn’t reckon with the possibility people might vote for other parties – the Greens for example – simply on account of their failures).

Never articulated, but undoubtedly there in the background were other assumptions about for whom Welsh-medium schools are provided. One needed to look no further than the arrangement for families in Butetown, who were apparently in the derisive position of their ‘local’ Welsh medium school being in Gabalfa (to those unfamiliar with Cardiff’s geography that’s a 5 mile drive across the city centre).

The absence of Welsh-language provision at primary level was eventually responded to with the establishment of Ysgol Hamadryad after a hard fought campaign, and on account of the progressive Phil Bale taking over as Labour leader, replacing Russell Goodway’s faction. However, since the latter installed Huw Thomas as leader following the 2017 Council Elections, progress at secondary level has mirrored progress more generally in terms of Welsh-medium education across the city – that is to say there has been next to none.

Again, the pattern of secondary school location tells us where the powers that be think Welsh-medium provision should be focused: in the more salubrious north of the city (albeit in second-hand buildings). This identification of Welsh-medium education with the middle class obviously serves to reinforce prejudices many in Welsh Labour have been only too eager to peddle, and who are completely ignorant of the demographics of the Welsh-speaking population outside of the capital city.

Consequences

The result is that the southern arc, from Ely to St Mellons – an area it is said would be the poorest Local Authority in Wales were it a separate entity – has not one Welsh-medium secondary school. That is a population on one count of approximately 150,000 people denied anything approaching a community secondary school, the biggest lacunae in Wales with regards to secondary Welsh-medium education, by some a distance (for scale, Ceredigion has a population of 71,000, and 6 of the 7 secondary schools offer Welsh-medium education).

This gap has material consequences, making Welsh-medium secondary education less accessible and less attractive in the south of the city – where children must go (often very far) out of their own communities to gain access. Moreover, it is families in Grangetown and Butetown who have had to fight for places in their catchment school of Ysgol Glantaf over the last couple of years. Those who do go, face more challenging circumstances in particular around extra-curricular activities before and after school, so vital to one’s school life and friendship groups.

One might suppose that resolving the issue would be a priority for the Council leader, Huw Thomas, like myself another Welsh-speaker from north Ceredigion. After 8 years of stagnation under his lead it would be a positive note on which to end his current term as leader, as the Senedd beckons. Cardiff Labour’s u-turn on his 2019 endorsement – and referring to their own failure to increase the numbers in Welsh-medium education as a justification for rejecting the idea – certainly suggests the need for boosting their ambitions.

On the basis of personal experience, however, I don’t hold out any great hope. I met him in expectation when campaigning for a Primary School, as he was at the beginning of that period a Cabinet member (for Culture, Leisure & Sport). The gist of his response was that his Cabinet colleagues held little interest in the matter and it was not a cause that he was going to exert any significant influence or energy in pursuing. His guarded words in the wake of the burgeoning campaign for a Welsh medium secondary school suggest to me there is little appetite for going above and beyond this time either.

Short changed

Who needs enemies, with friends like these, one might ask on behalf of the Welsh language. One might equally ask the same on behalf of the people of Cardiff’s southern arc, who have been loyal to the Labour Party for so long, and yet are left short changed time and again, with the Welsh-medium secondary education situation arguably being towards the thinner end of a very large wedge. Access to English medium secondary schools is one such example, where one in five children in Butetown are denied a place in one of their 3 chosen schools.

But this is why, of course, the Labour Party finds itself in such dire straits generally. In Wales their systematic failures around the Welsh language are emblematic of their ‘Welsh Way’ (spray-painting it Red won’t make any difference, sorry Eluned). The empty rhetoric of radicalism is married with a thoroughgoing neoliberalism and the type of inaction and lack of conviction that is infecting not only the fight for the language but our politics in general. All this while treating the communities that need their help most with disdain. Indeed, Cardiff Labour perfectly distils the essence of the Party’s wider issues.

The battle will continue, and it will be won. But this will be in the face of a deep political rot that has set in.

In the words of Dewi Pws’s famous song, inspired by Cardiff, mae rhywbeth o’i le yn dre.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Excellent piece, especially regarding the need to provide WM education for all, not just the middle classes. I’d just note that I believe Ceredigion is also lacking in WM provision at secondary level – it has only 2 out of 7 secondaries designated WM (Penweddig and Bro Teifi) – the others are not designated so. Yes, they may have many Welsh speaking pupils and teachers, but we cannot rely on Welsh being a community language any more. In many ways Ceredigion is more like Cardiff and the Valleys these days, with Welsh being a minority language. Which means we have… Read more »

Heartbreaking in so many ways! Firstly because my Taid was from Abersoch. Going to sea at 14, he settled in Liverpool. Many years later there was discussion of setting up a Welsh-medium school there. The Welsh community decided against it (not my parents’ wishes). Somehow I have retained my language, with a lot of help from 3 years college in Aberystwyth. Now in Cardiff, my sons have had the benefit of Welsh medium education, including at Glantaf. The children of all citizens of Cardiff, our capital city lest it be forgotten, should have access to education through the medium of… Read more »

Well I cannot fault the point made but I would point out that Swansea went through the same fight. Whilst the middle class population on the Gower had their Welsh school, Swansea North and East parents (that’s a population of thousands but they are mostly living in huge council housing estates so their voices counted for nothing) were told that there was “no demand” for another Welsh school on their side of the city for DECADES. It wasn’t until they had no choice but to close Penlan boys’ school due to falling numbers and they were left with a massive… Read more »

For decades Swansea was shocking for WM education provision. I was a teenager in the far end of Gower in the 1980s – the only WM option would have been Ystalyfera – with no school bus there, and literally passing Gowerton Comp. EM school on the way. I thought Ysgol Gyfun Gŵyr would have improved things – so disappointing to hear they cherry pick some kids and exclude others. Governing body needs a big kick up the proverbial. Anyway, what are the primary schools doing? They should be the start point of kids’ Welsh language journey & set them up… Read more »