Interview: Meirion Ginsberg discusses his outstanding new exhibition, Rhyngwyneb / Interface

Stephen Price

2026 is off to a strong start in the Welsh art world, with a powerful collection of new works by Meirion Ginsberg on show at Llandudno’s Ffin y Parc Gallery.

Born in 1985, Ginsberg is one of Wales’ most talented and sought-after artists, with work held in prized collections, and repeated sellout shows. He trained in Cardiff and currently lives and works near Chester.

His current show, which opens officially on 23 January but can be viewed online now, follows Ffin y Parc’s winter break, and their decision to spotlight Ginsberg in a solo show is a bold, brave one – a promise of colour, excitement and something new.

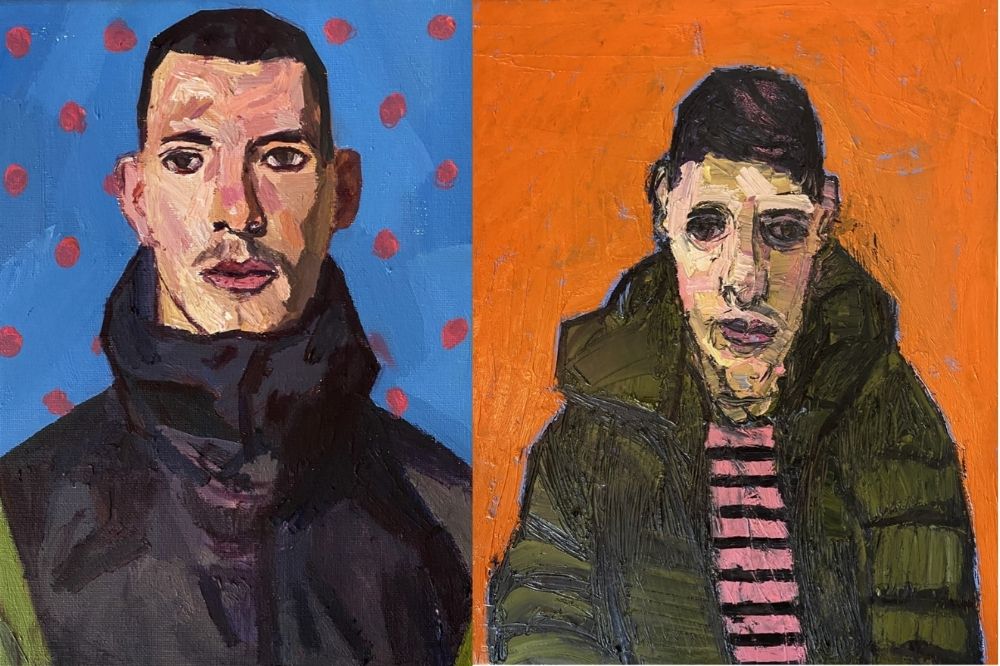

Most of the show, titled Rhyngwyneb / Interface features portraiture, with his subjects posing for us – their outfits and their adornments, still and silent. They watch or stare at us casually, or perhaps they attempt to avert their eyes, to evade our scrutiny.

Ffin y Parc write: “Meirion’s subjects are smart, self-possessed and forthright. He draws some of his inspiration from advertising and magazines, where presentation is all. Where illusion triumphs. They display the trappings of success: sleek hair and good clothes, jewellery.

“They go on holiday and recline by the pool! And yet… Meirion also has deep-rooted punk sensibilities which run counter to polite and straightforward expressions of docile conformity.”

Throughout the work, Meirion offers contradictory signals – sly details, ‘tells’ and red herrings. Ffin y Parc add that his “apparently straightforward portraits become tricky and ambiguous, playing with ideas of authenticity and performance. Navigating between the comforts of communication and concealment.”

Ahead of the show, we caught up with Ginsberg to discuss the new works and to talk technique, process, influences, and the impact of growing up in Eryri.

Reading your artist statement on the Saatchi website, you mention your love of mark making and the work of Norman Rockwell and Frances Bacon in particular. As your art has progressed over the years, do you still find yourself returning to these two greats? Or have you found room for more?

Both Norman Rockwell and Francis Bacon remain an indelible influence on my work. I discovered both artists at a very young age. The cinematic scope of of Rockwell’s story telling had me poring over his work on an almost daily basis. His paintings have a comic book immediacy and incredible sensitivity in subject, peppered with humour and warmth. Above all, his painting ability captured my imagination and really lit a fire in me; drawing religiously and trying my best to imitate his technique. It certainly was good training and helped improve the quality of my mark making.

Francis Bacon’s work struck me in the way I imagined he would want a viewer to respond to his work. I remember finding a book titled ‘Bacon’. The reason I thought it was called ‘Bacon’ was the paintings suggested meat to my 7 year old eyes. I was fascinated by his application of paint and his bruised colour palette.

I don’t look at current artists all that much; I’m not hip to new trends. The last books I looked at were ones on Giotto and Titian. I can’t believe their invention; their work look as current, inventive and cutting edge as when they were produced. The last exhibition that really sparked new ideas in my work was a show of ancient Egyptian art. Whenever I’m at the Storyhouse in Chester I pick up a few books and digest whatever catches my eye. It all absorbs into me like a sponge and is drained in a subconscious manner into my work. I interpret anything and everything that has the potential to compel a creative desire.

There, you mention the humour in your artwork, which is of course, more subversive than obvious – is this an instinctual thing that you are perhaps ‘channeling’ for want of a better word i.e. something you notice later on, or is your intent to amuse?

The humour in my work is meant to be subtle, possibly provoking a smile here and there. I’m certainly not trying to be David Shrigley, however, I do think that humour is lacking in the general art world. My entré in to the world of art was mainly considered low brow: cartoons and comics which are full of humour. I’m certainly not trying to make high brow pictures, and in a way I’m poking fun at the general seriousness of the art world.

The painting practice is for my amusement, therefore I include things that make the process interesting to me and humour happens to be an element. It could be colour choices, bold patterns or the combination of objects which conveys a narrative.

Humour is essential in my life and so it should be in my work. After all, they’re a sort of diary of my progression as an image maker and in turn of my life on the whole. I’m hoping to be rewarded with a smile rather than a guttural laugh. I’d be a little concerned if it were the latter.

One thing, I feel, sets artist apart from artist is colour, and you seem to have an inclination not only for the joyous, but also the complementary. Again, is this instinctual, or something honed and honed over time?

The use of colour is always playful, and perhaps the element that provokes humour the most over subject matter. I’ve always gravitated towards colour, but I have no understanding of colour theory. I don’t really know what warm and cold colours mean.

On the whole it’s purely instinctive and not a huge amount of brain power goes into the decisions made regarding colour combinations. Often it’s whatever feels right at the time. The worst that can happen is that the combinations don’t work and that I have to change them at some point. Roll the dice and hope for the best.

One can’t help but notice the importance of Cymraeg within your works – from scrawls within, to so many of the titles – can you share how important ‘Cymreictod/Welshness’ is to you and your work?

Welshness is a vital ingredient in my work for many reasons. Having been raised in a purely Welsh speaking community has indelibly shaped me. It offers a unique perspective to the rest of Britain, with history that’s passed down centuries through language and stories. All of this energy subtly resonates in my work without the conscious effort of making my work specifically about Wales and Welshness.

Another element I think was vital in my early years was the fact that museums were nowhere to be seen in rural north Wales, and therefore I had to imagine what my favourite art looked like in person. I used that imagination to make my own interpretations of my inspirations, which has spawned a Celtic, clunky rebelliousness in the work.

The use of Welsh as titles is my little contribution of keeping the language and culture alive. We all need to do our part to keep the flame alight. I’m proud to say that my son, Osian, is an English born, Welsh speaker, and the only language we communicate together in. Big win.

Do you feel that not living in Wales impacts your work at all? Because so many artists not from Wales, I see, use the ‘based in Wales’ tag, whereas we always, always, take Wales with us.

Growing up in Eryri has a profound impact on an individual. I honestly didn’t see what was so special about the place until I left, taking it for granted and thinking everywhere is the same. How wrong was I. When I lived in Liverpool I had a great longing for the mountains. Although Wales was only down the road; it’s not quite the same being a visitor than being immersed and living among the misty mountains.

I’m not entirely sure if being in Chester has changed my work or not, but my instinct tells me it has. The inspiration of just wandering down lanes and fields of home fills me with inspiration and the need to work. It’s magic that I haven’t the ability to express. I might end up back there one of these days. The kids are settled in school and that, so let them be at the moment.

Ever the hypocrite as I write in a hole-ridden dog-hair-covered hoody with a broken zip, I’ve gone so far as to have written opinion pieces on how poorly we dress nowadays compared to a timelessness and grace of some (not all) people in the past, and one thing that strikes me about your work is, you don’t ‘dress’ your subjects for the easel. Yes, many are in their Sunday best, but side-by-side with hoodies and trackies. Do you have any goal in mind with that approach?

My subjects’ clothing tend to represent day to day wear. I’m often inspired by the colour of a dress, a badge covered denim jacket or a patterned scarf.

However, in practice, choosing the garments tends to happen quickly without too much thought; I start with one piece of clothing – perhaps a jacket from a fashion magazine – and then a domino effect begins to happen once the seed is planted.

© MEIRION GINSBERG

I’ve learnt that getting ideas down quickly is vital before I begin second guessing. Thinking too much can zapp all creativity. The first idea tends to be my best one.

Taking just one piece, Crying Twins, and relating it back to your Saatchi write-up, you mention an early love of comics, and I’ve never been afraid to acknowledge my love of the pre-90s Beano, Roald Dahl, Babette Cole etc and the impact they had not only on my writing (and doodling) back then, but even up until today. Sharp, sharp humour and hook. I see in your work too, much subversion, humour and storytelling. Do you ever return to childhood inspiration, or do you feel it’s now more in the subconscious?

I think the world we grew up in was a simpler yet wildly more subversive compared to our modern world.

Being bundled with buddies in the back of our friend’s dad’s van for a trip to the beach, being raised in a household of chain smokers, staying out all day and night without communicating with parents, drinking in pubs, clearly looking under age, Roy Chubby Brown being a mainstream comic. All these were the norm and perhaps are the subversive, humorous ingredients in my work.

I’ve also gravitated towards subversive art my whole life. I like work that I initially can’t quite figure out, or is unpleasant, but somehow I’m urged to give a second go, third go, until it becomes my favourite thing. I’m introducing my kids to all the punk stuff I like. Proud to say my 8 year old son is a fan of Bad Brains.

The comic that hugely inspired me was 2000AD, not that I read all the stories, however, I devoured the eclectic variety of artistry and the edgy, broken and bruised characters. I’ve definitely thrown these in the mix.

Looking at this new body of work, I wonder if you feel there is a thread that ties all the pieces together?

I think tone and colour blending is the thread that ties this new body of work together. The backgrounds convey a different sort of depth to my previous work.

Its a progression in my practice. It may be unique to this phase of my oeuvre as I’m not entirely sure where my work will be going next.

And can you tell us more about the process of making them? A photo from Ffin y Parc showing you among works and pages from sketch paper and pad suggests there has been a lot more going on behind the scenes, falling by the wayside….

The process generally starts by finding a face and going from there. Sometimes I’ll map a few figures and then it’s a matter of creating some sort of collage.

I often describe my figures as Frankensteins; they are pieced together from numerous sources.

Ideas for larger paintings are often lifted from a doodle or a primitive composition, but the process of applying paint is similar to the other paintings. My ideas are never fully formed so there’s room for interpretation during their creation.

The sketches are often akin to stick men – ideas come quickly. The execution of the final work can be a long and arduous task; from a five minute sketch to a two month painting. Sometimes the stars align and all is hunky dory. On the whole there is a lot of editing. I think the old adage applies: the swan swims gracefully but the paddling goes unnoticed.

Your self portrait, however, sings a different song. The other faces tend to be unashamedly beautiful, but you’ve not been so kind to yourself, dysmorphic even, can you tell us why? Perhaps influenced by mind more than mirror?

The self portraits were direct interpretations of some very quick drawings. I often draw without looking at the paper and channeling all my observation on to the subject. I think there’s an honesty in these drawings that can’t be achieved from pure illustration. They have an intensity that I can’t put my finger on.

I wouldn’t call them great feats of technicality, but I find them far more interesting than a drawing I’ve laboured over for hours. It must be the spontaneity and unpredictability of the outcome that makes them interesting to me.

I wondered what my paintings would look like using a similar process to my drawing. These were the results.

Meirion Ginsberg’s latest show, Rhyngwyneb / Interface is available to view and purchase online now, or can be viewed in person at Ffin y Parc, Llandudno, from 23 January – 14 February 2026.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.