Letter from Ukraine: When Darkness Becomes a Weapon

Yuliia Bond

I am in Ukraine as I write this, moving between my hometown, Marhanets, and Kyiv as winter deepens and electricity disappears without warning.

People ask how the trip is going, and I struggle to answer. “Fine” feels dishonest. “Hard” feels inadequate. What I feel most is a heightened awareness of absence – of light, of heat, of certainty – and of how fragile ordinary life becomes when electricity, something we rarely notice, is deliberately taken away.

When I crossed the Ukrainian border, I cried – not from sadness, but because something in my body finally released. If you have ever been displaced, you understand that feeling before you can explain it. Being somewhere that speaks your language, even briefly, feels like rest. No translating yourself. No explaining. Just being.

Belonging is not about comfort. It is about your nervous system finally being able to breathe.

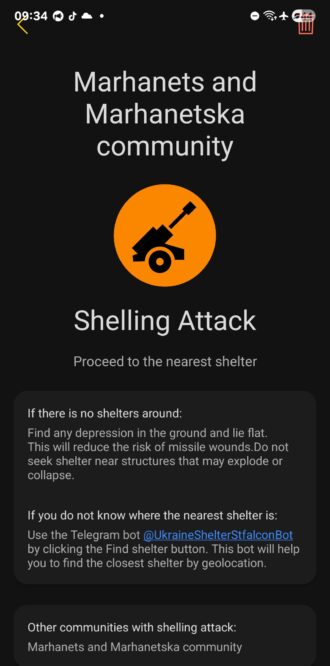

I travel between Kyiv and my hometown, Marhanets. It lies just six kilometres from the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, the largest nuclear power station in Europe, which was occupied by Russian forces in early March 2022. Since then, Marhanets has lived as a war zone. Shelling is part of daily life there – heard day and night, woven into the background of ordinary routines.

When you go there, you never really know whether you will come back alive. People learn to live with that uncertainty, because there is no alternative. When you walk or drive, you do not just look left and right – you look up, and you listen. Drones are frequent there, and sound becomes a warning system.

Marhanets is one of the few Ukrainian cities to have been officially awarded the title of Defender City. It became a shield, holding the line, absorbing pressure, protecting territory beyond itself. But that recognition does not make daily life safer. It only names the reality that people there have been living with for over three years.

In Kyiv, the war announces itself through absence. The absence of light. The absence of heat. The absence of predictability.

It also announces itself by name: drone attacks, missile strikes, air-raid sirens, explosions – sounds that cut through the dark and make sleep provisional.

Over the past days, Russia has launched another wave of strikes on Ukraine’s energy infrastructure. These are not random targets. They are power stations, substations – systems designed to keep cities alive in winter. Hundreds of thousands of civilians in Kyiv and other major cities are left without electricity, heating, and water, as temperatures fall to minus twenty degrees.

This is not collateral damage. It is strategy.

When electricity disappears, life contracts. You plan your day around power schedules. You charge your phone whenever you can. You boil water quickly, just in case. Elevators stop working. Traffic lights go dark.

At night, entire neighbourhoods sink into a darkness that feels heavier than ordinary night. Silence becomes suspicious. Every loud sound tightens your body, even when your mind knows it is probably nothing.

People adapt, Ukrainians always do, but adaptation does not mean acceptance.

What strikes me most is how calm everyone looks. No panic. No hysteria. Just a collective, exhausted competence. People share information, check on neighbours, help elderly residents carry water upstairs when pumps stop working. Survival becomes communal.

There is a hairdresser in Marhanets I have gone to for years. Every time I return, I go back to her – same place, same chair, same quiet conversations. Recently, a drone hit that area. The salon was destroyed. She survived. And she is still working.

Not in the same building, but somewhere nearby. Because people have to work to survive. That is why, even in a war zone, Ukraine functions. Shops open. Hair is cut. Trains run. Not because life is normal, but because stopping is not an option.

Marhanets, though much smaller than Kyiv, carries a different weight. It lies closer to the front, closer to occupied territory, closer to the line where maps stop being abstract. The town has lost people. Some were killed. Some left. Some never returned after 2022. Homes stand damaged or abandoned, familiar streets subtly altered, as if the town itself is holding its breath.

Being here reminds me that war is not only about explosions. It is about erosion. About years of interrupted lives. About children growing up with air-raid sirens as background noise. About parents who measure happiness not in plans, but in survival – another day without loss.

New Year’s Eve I spent with my mum, in a war zone, just kilometres from occupied territory. She baked the same pastries she used to make for my birthday when I was a child. After years of separation, that small, ordinary act broke me more than any explosion could have. It was a reminder of what war tries to erase: continuity, memory, belonging.

These days, happiness feels brutally simple. Knowing your family and some friends made it through another day.

While I am here, I hear another story. An 84-year-old disabled woman whose home was destroyed. She is now homeless, in the middle of winter. There are millions of stories like this. She is not an exception. She is what displacement looks like when you strip away statistics.

People often confuse migration with displacement. They are not the same. Migration involves choice – when to leave, how to prepare, where to go. Displacement is leaving because staying becomes dangerous. It is not a plan; it is a reaction. Not opportunity, but survival.

I know that when I return to Wales again, the contrast will be overwhelming. For a while, I will still hear sirens and explosions in my ears, even when everything is quiet. It will take time to remember that not every loud sound signals danger. To adjust to people smiling, laughing, being relaxed.

And yet, after everything people survive, it is painful to realise that some still see refugees as problems rather than human beings. As burdens rather than neighbours. As numbers rather than lives already broken once.

That is why the most cruel thing anyone can do after war, after loss, after displacement, is to make someone feel they do not belong. When everything else has been taken, belonging is often the only thing left.

What is happening in Ukraine now – the deliberate targeting of energy infrastructure, the forced displacement of civilians, the deportation of Ukrainian children, the destruction of hospitals, schools, and churches, and the suppression of Ukrainian language and identity in occupied territories – is not incidental. It is systematic.

Many countries and institutions have already recognised Russia’s actions in Ukraine as genocide. That recognition matters. Not symbolically, but legally and historically. It creates pathways for accountability. It names reality.

if the Senedd and the UK Parliament were to formally recognise the genocide of Ukrainians during Russia’s war, it would be a powerful act – not just of solidarity, but of justice. Time matters. Justice delayed becomes denial.

Wales often speaks about peace, fairness, and care. Those values matter most not in statements, but in how we respond to people who arrive here carrying trauma instead of luggage.

Darkness is being used as a weapon in Ukraine right now. Light – political, moral, and human – is something the rest of us can still choose to provide.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

That is terrible. I cannot begin to imagine what it must be like. I see dreadful images in my head of what it must be like but it must be hundreds times worse than that. Putin is a murderer and a monster and the sooner the whole world turns against him the better. How one man can rule and manipulate millions of Russians is unbelievable. JUST ONE MAN!! The Russian military should declare that they are no longer prepared to fight for the sake of one man’s ego and greed. He should be arrested and dealt with. He is crazy!!

Dyma beth yw dewrder Diolch am ddangos y fath esiampl.

Us Welsh will never forget the very same fighting spirit of the Ukrainian miners when we were under attack from the British government in the 80’s.

The support they showed us by sending food, money and supplies was unfaultering and Ukrainian people can call Cymru home as long as they need.

Thank you for this story, thank you for having our backs and thank you to the many Ukrainians learning the Welsh language. This shows a level of respect we don’t see from others that land on our shores.