Madam Wen and the two rules of the Welsh novel

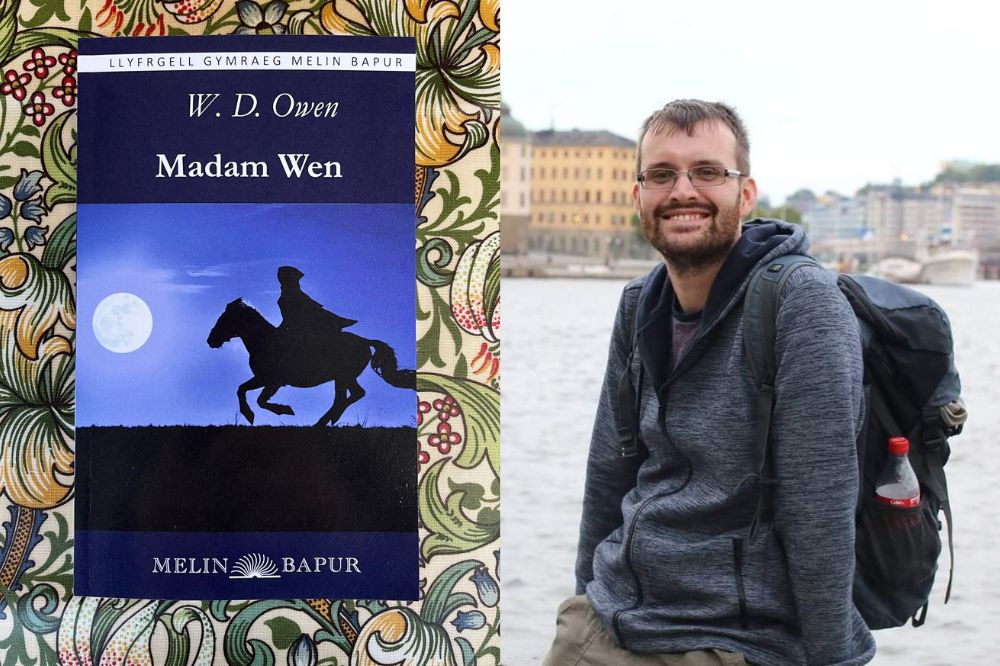

Adam Pearce, Editor Llyfrau Melin Bapur Books

Writing novels in Welsh in the nineteenth century was, more often than not, a thankless task.

For many decades authors in this ultra-religious society had to contend with the widespread idea that novels were at best merely frivolous, and at worst outright dangerous to the reader’s moral character.

Even when this attitude had begun to fade towards the end of the century, its legacy lived on: driven perhaps also by a sense of inferiority common in minority cultures, and reinforced by the Blue Books of 1847, that notorious educational report which portrayed the Welsh as immoral and ignorant and their language as backwards and uncivilised.

There was a definite sense that, if the Welsh were to write novels, then they should

- portray Welsh life or Welsh people ‘as they are’ i.e. positively.

- do some kind of moral or spiritual good (“lles”) to the reader.

Rhys Lewis

This ideal was best exemplified by Daniel Owen’s Rhys Lewis (1885), by far the century’s most popular novel: it did both these in spades, and set a tone for novels in Welsh for the next few decades.

The novel has its merits, many of them in fact, but to modern readers it can feel like a sprawling mess, its limited plot stretched over too many words and its main character a vapid shell of a man far less interesting than the odd eccentrics who surround him.

Rhys Lewis did a very great deal to legitimise the novel genre, but perhaps also ossified the two criteria above as the overriding concerns of the Welsh novelist for the next half century.

This dual obsession can be observed in contemporary commentaries and reviews—one advertisement reassured the reader that a novel contained “nothing to offend the reader, and a great deal to do him good” —but left its mark on the novels themselves as well, with the drunk (doomed to either reform or meet a sorry end) almost ubiquitous, and thinly veiled lectures on temperance making their way into even some of the best novels of the period.

To be clear; neither of these goals are in and of themselves bad things. However, an obsession with social portraiture and lles all too often came at the expense of the novels’ plot, and their aesthetic and literary merits.

The critical consensus today is that Owen’s next novel, Enoc Huws is in fact superior to Rhys Lewis by almost any literary measure; but this consensus didn’t emerge until much later.

Contemporary critics wrote it off as a lesser work because its comedy and its much more secular tone compared to Owen’s previous novel.

Deviation

Those novels which deviated too far from these goals were often simply forgotten: after serialisation in the newspapers, often anonymously and typically marketed as light entertainment on Tudalen y Teulu (the Family Page), the majority of the novels were forgotten.

The period immediately after Daniel Owen was a golden age for Welsh prose (in terms of productivity at least) but is barely acknowledged in some of the standard histories of the Welsh novel, and novelists like T. Gwynn Jones and Gwyneth Vaughan who should be considered giants of our literary heritage are almost completely ignored (Gwynn is given his due as a giant of Welsh poetry, but his entry in the Bywgraffiadur completely neglects to mention that he wrote some fifteen novels and hundreds of short stories).

Even as late as the Cydymaith i Lenyddiaeth Cymru, written in the 1990s, we still see the absolute nonsense narrative that nothing worthwhile happened in the Welsh novel between Daniel Owen and Kate Roberts.

The good news is that, even if the critics ignored them, the novels still exist; and are there waiting for those readers who are willing to seek them out, and it is often the very novels which were ignored altogether that hold the most appeal for readers today.

Mission

Part of our mission with Melin Bapur’s Llyfrgell Gymraeg series is to bring these wonderful books back in from the cold.

One genre of writing that was never going to meet the dual-standard was the adventure novel. Whilst W. D. Owen’s Madam Wen, originally serialised from 1914-17, has hovered on the edge of the cultural consciousness, even being one of the few Welsh novels to receive a film adaptation (in 1982), it is not a novel you are likely to find on a university syllabus.

When mentioned at all it has tended to be in passing, perhaps with the criticism-by-stealth of referring to it as a rhamant (romance), or even worse, by praising it as a book for children.

Absolutely nothing wrong with children’s books of course, but saying something is good for the kids is a convenient way for critics to avoid taking a novel seriously as literature.

And yet in fact, Madam Wen is a magnificent novel: fast-paced, tightly structured, with a carefully crafted plot, and a central character who must surely be one of the most immediately appealing and likable in all Welsh literature of the period.

The titular character is the leader of a group of bandits on Ynys Môn in the early eighteenth century: we see her prove she can ride a horse brilliantly (echoes of Rhiannon in the first branch of the Mabinogi), and that she is a swordswoman of magnificent skill, and that she is also able to outwit a pirate captain on the high seas.

A Welsh epic

In each case, our heroine is seen besting a male opponent in a traditionally masculine field. She is also, of course, an heiress in disguise who has sworn to reclaim her father’s lost inheritance (the reader is in on the secret from the beginning).

It isn’t completely free of patriarchal elements (this is 1914 after all) but if you are looking for a classic Welsh novel with a strong female lead, this is it.

In fact, “immediately appealing” is a good way to describe Madam Wen the novel as much as the character.

This is a novel with a very strong Welsh grounding that is impossible to imagine being written in another language, yet it is also an epic, a blockbuster with pirates, sword-fights, pistols, Jacobites, bandits, and of course, a heady dollop of steamy (if chaste) romance.

The prose is elegant, fluent and simple with none of the bombast that so often infects Welsh prose of the period.

Whilst reading Madam Wen one is struck by the fact this novel isn’t better known, but then perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised, given how little it conforms to the Welsh novelistic ideal.

Rediscovery

How many other more similarly wonderful adventures might be out there awaiting rediscovery? Sadly, we can be fairly sure there are none by W. D. Owen.

Although it was only his second novel, Madam Wen was to be his last.

Its publication was delayed by the war, and when the author from Rhosneigr finally did see his story as a book eleven years after its originally serialisation he would die a few weeks later of the tuberculosis that had plagued him throughout his life.

At a stroke, Wales was robbed of a man who might, in another universe, have become our very own Robert Louis Stephenson.

Celebration

As with many Welsh novelists of the period, one is struck as much by how good their work is as by a sense of the loss of what might have been: whether through untimely death (W. D. Owen, Mary Oliver Jones, Gwyneth Vaughan, Richard Hughes Williams, and Daniel Owen himself) or because they gave up writing novels (T. Gwynn Jones and W. Llywelyn Williams), a huge number of our best novelists had, one suspects, much more to give.

Still, better to celebrate what is rather than mourn was not; and there can be no greater starting-off point for those who would like to explore ‘classic’ Welsh literature than Madam Wen (yes, even younger readers).

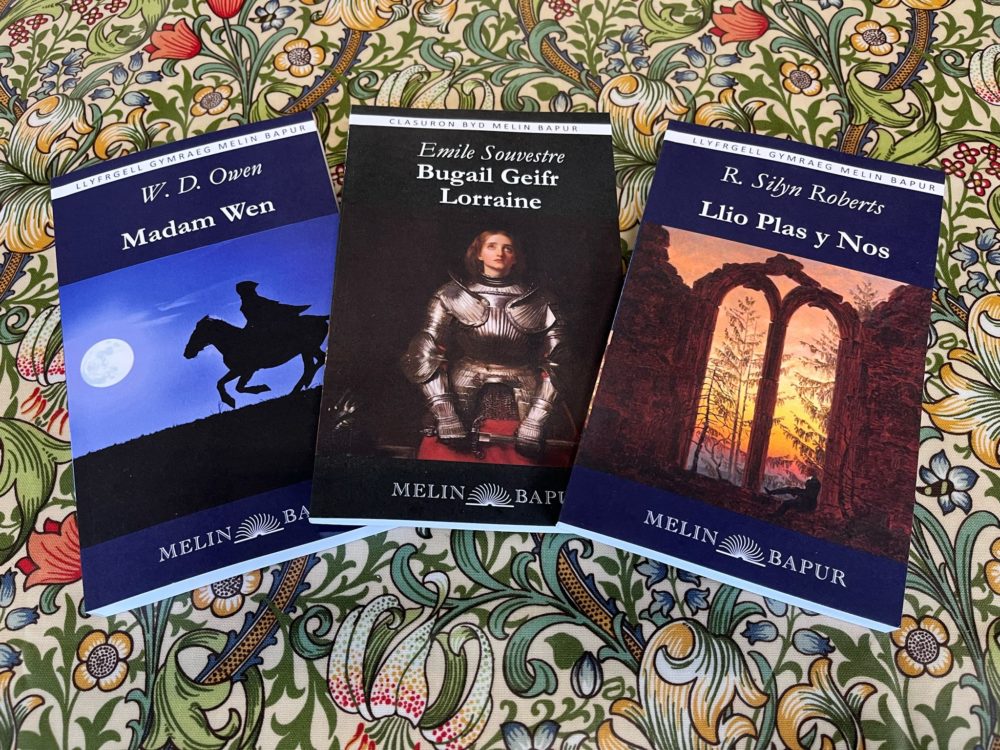

Madam Wen is available now in paperback from www.melinbapur.cymru for £8.99+P&P. Also newly released this week are R. Silyn Robert’s Llio Plas y Nos (£7.99) and Emile Souvestre’s Bugail Geifr Lorraine (£6.99).

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Nice to see our own WD recognised as the great story-teller he was. In the days of the Jacobite rebellions, the Afon Crigyll was much more of a thoroughfare than it is now. Farm produce was shipped out and money and guns could be brought in under the cover of night by the Jacobite interest. For readers who do not fancy tackling this great book in the original Welsh, a translation into English (by Jenni Wyn Hyatt) was published by Tim Hale as part of his book The Rhosneigr Romanticist. This gives a full biography of WD Owen and also… Read more »