Making Tracks: Bargoed and Gilfach Fargoed

Jon Gower

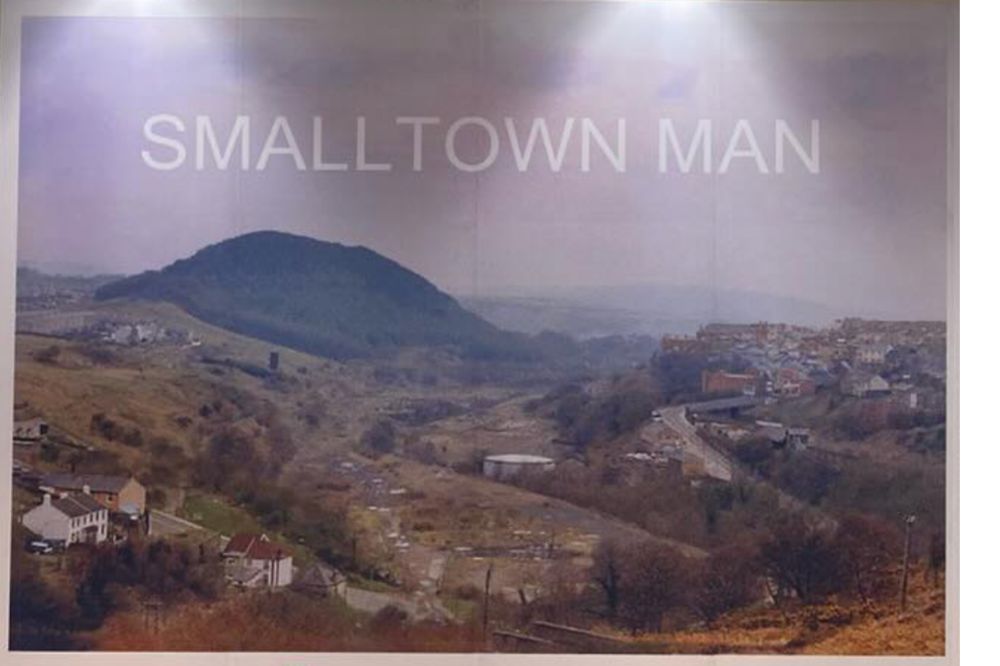

The Bargoed coal tip in the Rhymney valley used to be the biggest in Europe, so big in fact that some locals called it a mountain.

This huge mound of spoil was the consequence of Bargoed colliery’s enormous productivity. On the 10th December 1908 its colliers set the world record by extracting 3562 tons of coal in 10 hours, which they beat the following April by lifting 4020 tons to the surface.

By the mid 1930s over a thousand men worked here, continuing as a major source of employment until it was closed in 1977.

During the decades that followed the closure the tip was landscaped and planted with trees as Conor Willmott, the Ranger for Coetir Bargoed Woodland Park recalls: “I was born in 1993 so I can just about remember the area being grassed over in the late 1990s, the engineers landscaping everything and planting small tree whips.”

Between then and now Conor studied marine biology and worked on a number of offshore islands, including Lundy in the Bristol Channel, the Farnes and Arran and Islay off the Scottish coast. Now he’s responsible for “A long, thin country park which follows the line of the river valley.” It’s accessible from two train stations which both sit adjacent to the park boundary, namely Bargoed and Gilfach Fargoed, a small halt near the heart of the woods.

A great deal of the park is “brownfield” land reclaimed from three local collieries – Bargoed, Gilfach and Britannia. Which explains the name of the nearby Britannia estate, source of mothers with prams and children on their way to school.

On a drizzly January morning Conor takes me along the side of the Rhymney, today so charged up with rainwater it spumes white in places.

We pass through pockets of ancient, semi-mature woodland and stands of beech and oak, with holly, willow, alder and hazel as well as sycamore. “Later in the year there’ll be wood anemones, snowdrops and bluebells galore in the undergrowth.”

Conor points out places where water has scoured away the surface, landslips exposing the coal duff beneath. He explains that when the colliery was in existence the railway lines converged here and the river was diverted underground.

As we saunter along together he describes his job – thinning trees and occasionally bramble, creating new ponds such as the ones near the fire station and constantly dealing with invasive plant species such as Himalayan balsam and Japanese knotweed. There is birdsong galore and we note bright candelabras of catkins intimating spring.

We stop to chat with Suzanne and Gareth Thomas from nearby Fleur-de-Lys about the wildlife they spot on their perambulations with Benj the dog. Suzanne’s eyes light up as she recalls spotting otters. “We also saw the kingfisher a couple of days ago, just a blue flash that went down there. We don’t see him very often.”

Gareth loves the excuse for some exercise: “It gets us out of the house in the morning, otherwise we’d be couch potatoes. It’s a well-used walk, where regulars soon get to know each other and stop for a chat.”

One such regular is 88-year-old Lawrence Jones. A hardy fellow, he walks here every day dressed in shorts, other than two days last year when there was frost on the ground. “I can handle the rain and I can handle the wind but I can’t handle the rain and the wind together,” he tells us with a ready smile.

His daily routine involves following the same four-mile circular route, carrying a bag to pick up rubbish. In 2016 Lawrence had a stroke and maintains that walking has been fantastic for his recovery. In a sense, the whole park is about recovery, as nature’s greenery replaces the industrial greys and blacks of the past.

The artist Osi Rhys Osmond grew up in Bargoed and witnessed the green regeneration of the coal-black tip.

In an essay called “Cultural Alzheimer’s” he suggested that “To visit a tip in the process of re-greening itself is a profound experience – in fact the carbonised surface of the tip is analagous to the earth as it might have been in the beginning, as groups of simple plants begin the process of colonisation and conversion…”

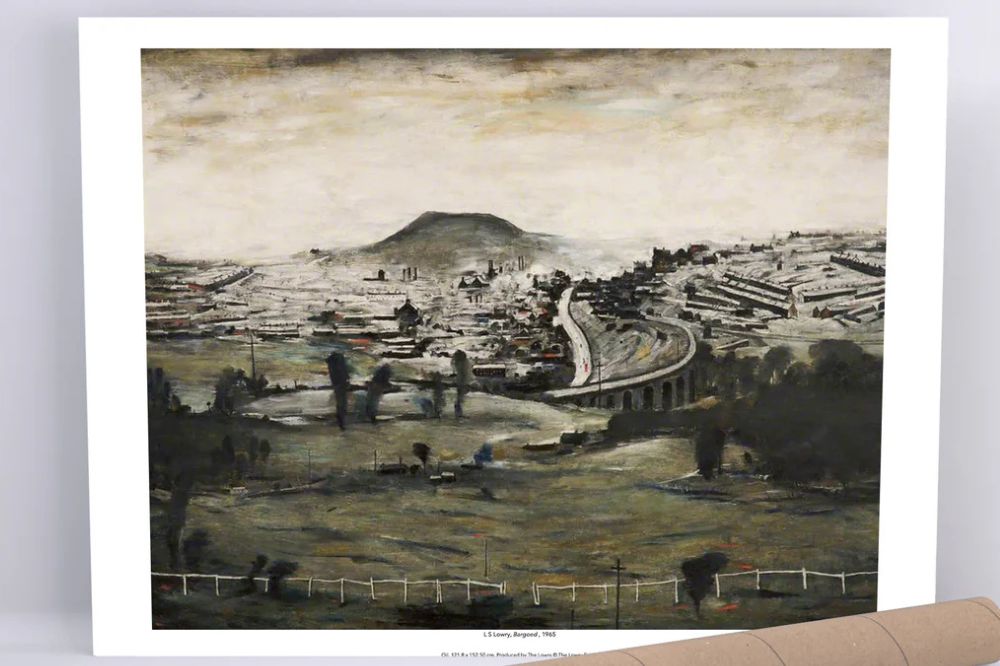

Not only did Osmond write about it he also painted the tip repeatedly. But he wasn’t the only artist to be inspired by Bargoed tip. L.S.Lowry painted it too, holidaying in south Wales in 1965 to create a work that now hangs in Salford.

As the psycho-geographer Eddy Street noted: “Lowry’s painting naturally forges the link between an industrial landscape, its underlying history and the ground on which it stands. He was able to see that in Wales there is a way in which nature is still larger than the havoc that men have inflicted…”

The artist and writer Anthony Shapland recalls standing as a ten year old to appreciate Lowry’s work on loan to Bargoed library, noting “How it was broader and looser than some of his other paintings. I remember being this close to the painting and seeing it was made of perfect brushstrokes, not small brushstrokes. It’s quite big and gestural in comparison with Lowry’s other stuff.”

As a boy Anthony thought coal was just something you put on the fire: he had no idea about south Wales powering the world. But he gradually came to understand how “The ground underneath and around us must be hollowed out, because something’s missing somewhere if you can build a mountain out of air.”

The tip itself made an indelible impression on Shapland: “The sense of it all being man-made and the thought of the hollowness of the land was really embedded in my young imagination. It was like a prop, and then in my 20s it started to disappear, landscaped away. Everything felt shaky.”

The place appeared in Shapland’s work as recently as last year, in the form of a stereoscopic billboard image made for his exhibition ‘Celwyddgi, Celwyddgi’ at Aberystwyth Arts Centre. It features a 1987 photograph of Bargoed taken from the spot where Lowry stood to paint.

The tip also manifests itself in Shapland’s much lauded novel A Room Above a Shop: “Behind the town the hill, rises, grown from mining spoil, load by load.

It’s an unnatural mound poured from above, like sand funnelled through a slow hourglass. It grew until it settled, leaning back on the hollowed east mountain behind, an uneasy, weighty twin. The land held with trees in fear of slip.”

Osi Rhys Osmond suggests that unnatural mound could be a lawless place, too. “The tips also represent an unbound landscape, a landscape of undefined possibilities – a place of no rules. Tips usually exist in uneasy cohabitation with local people, who find in them useful anarchy of opportunity. This is a place to ride a motorbike when you’re too young or have no paperwork, burn a mattress, dig a hole for no particular reason, get rid of some rubbish, look at nature.”

Anthony Shapland agrees. Although he and his brothers were prohibited from playing on the tip they were drawn to it like ardent moths to a flame, crossing the river by balancing on a pipeline.

“There were old mine workings pumping out water so you shouldn’t have been there, but it was just too tempting. It was a great place for bikes and this was just before the BMX craze, when my brother Patrick was an early adopter. He had one, I had a bloody Raleigh Grifter that weighed a ton.”

Richard Poole, who lives in Bargoed, has been monitoring and ringing dippers for the past 25 years, mainly on the rivers Darren and Rhymney.

The dipper is an extraordinary bird, the only British songbird that swims under water. It is also a very good indicator of a river being in good health.

Richard informs me, “There are a lot more dippers now than I’ve ever seen. Last year the countryside team from Caerphilly Borough Council erected dipper boxes.” Many of these were subsequently occupied, with dipper territories abutting each other. The team has placed boxes for both grey wagtails and dippers in the same locations, downstream-facing for dippers because the birds always like to fly upstream to a nest and then upstream-facing for wagtails.

It’s a far cry from a river once described by the poet Harri Webb as a “sewered drab.” The Rhymney once ran black with coal dust while acid rain – caused in part by planting conifers on the uplands – led to poor river health in the seventies. Richard says it “Affected birdlife and fish but plantings of broadleaved trees in the uplands has helped remove the acidification. Rivers in general have cleaned up a lot.”

He points out that the dippers on this stretch have already paired and are building nests at the end of January into February “They’ll be on eggs by March. If the weather’s been nice, at the end of March the young will be leaving the nest.”

The chicks appear as the river temperature starts to warm up, when the adult birds will be feeding on aquatic invertebrates such as caddis fly and stone fly. The grey wagtails will meanwhile be taking insects above the surface, such as gnats as they emerge.

The writer Patti Webber is a fan of dippers as she demonstrates in “A Dip in the River,” which features a lovely rugby analogy for the way the dipper shimmies on a rock as it prepares to dive: “Fast flowing water suits one plump-looking resident, cinclus aquaticus, currently perched on a rock mid-stream, bobbing and curtseying as if on hinged legs. The water ouzel, or dipper, is not auditioning for a television talent show, but warming up for feeding with a spot of Dipper Dancing. It’s agitated stance, like a Dan Biggar preamble to the direct and rapid flight of the ball. The Welsh fly half employs a trademark, fidget-on-the-spot, pre-kick routine. The dipper does the same…”

Richard Poole tells me that not only can you see dippers doing their waggling Dan Biggar impressions as they stand on rocks but when the water conditions are right you can see them swimming under water.

He also tells me the area is brilliant for bats. “We’ve got noctules, which will come out before sunset. You generally see them flying quite high in dead straight lines and then suddenly diving, catching things like maybugs and beetles. We also have Daubenton’s bats roosting in old retaining walls.” This species is known as the “water bat” as it fishes insects from the water’s surface with its large feet or tail.

Richard is further pleased that otters pass through regularly. “Also, when the water’s clear at the right time of year you can see salmon and sea trout near Abertysswg. Lower down you can stand on the bridge in Ystrad Mynach near the Royal Oak and watch such fish in the river below. Around Llanbradach there are good populations of coarse fish such as grayling and chub, further indications of how clean rivers are these days.”

And as if more proof was needed we spot a cormorant standing in reptilian stance on a tree branch. Richard gets out his high-powered camera lens to capture the moment.

It’s a fish-eating bird standing sentinel above a river once biologically dead, joining the blue flashes of kingfishers and romps of otters. They are signal signs of nature still reclaiming industrial stretches of valley, brightening it into green.

Jon Gower is Transport for Wales’ writer-in-residence. He will be travelling the breadth and length of the country over the course of a year, reporting on his travels and gathering material for The Great Book of Wales, to be published by the H’mm Foundation in late 2026.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.