Making Tracks: Hawarden

Jon Gower

For a small Flintshire village the station platforms at Hawarden are uncommonly long. When the first passenger train stopped here in 1890 the village was much smaller than now. But it was the home of four times Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone, a man often regarded as one of Britain’s greatest statesmen.

He was quite a personality in his day. People would travel from far and wide to listen to him deliver speeches and attend fetes held on Gladstone land. On such days up to 32 trains arrived. To accommodate the crowds, special excursion trains were laid on to Hawarden, which explains the extended platforms on what was then the Wrexham, Mold and Connah’s Quay Railway, built primarily to serve the north-east Wales coalfield. Nowadays it sits on the Borderlands Line which connects Wrexham with Bidston on the Wirral peninsula, passing through villages such as Cefn y Bedd, Hope, Buckley and Penyffordd.

The polymathic Gladstone did a great deal in his day to inspire a sympathetic understanding of the historical value of Welsh culture. When he addressed the National Eisteddfod in Mold in 1873, for instance, he spoke fondly of the country’s “ancient history, the ancient deeds and the ancient language.” He would deliver another speech at the Wrexham eisteddfod of 1888 in which he expressly called for the Church, and by implication the British Government to recognise that language wholeheartedly.

Gladstone lived in Hawarden castle long enough to be referred to as “the village squire.” He allowed locals to borrow books from his library and when he wasn’t reading he might be sighted swinging an axe to cut down trees, a wildly energetic man’s form of relaxation. William Gladstone had married a Welsh wife, Catherine Glynne and became, in historian Kenneth O. Morgan’s opinion “Increasingly attuned to Welsh national sentiment as he was to Polish or Italian. Gladstone’s portrait flourished on the walls of farm labourers or miners’ cottages, a symbol of the new religion of the cult of Hawarden.”

William Gladstone’s great-great-grandson Charlie Gladstone became involved in running the Hawarden estate 20 years ago. Now 61 years of age, he seems to be imbued with oodles of Gladstonian energy and enthusiam, having had lots of experience in business, including managing rock bands. The challenges he met at Hawarden were multiple, he tells me: “The place was very run down, neglected and closed off. There was dry rot, wet rot, no functioning electricity. The roof and windows needed doing, the heating was antiquated: it certainly wouldn’t have passed any habitation test.”

“My father – a historian and an enormously cultured man, was obsessed with William Gladstone, seeing him as a deity – but he didn’t look after the place. Even in the Prime Minister’s study everything was covered in dust.”

Whilst Charlie is respectful about his famous ancestor he is also cautious about his casting too long a shadow: “I am very proud to be associated with him and I think his greatest legacy as a politician was that he was open to change. His history is written and it doesn’t need me to go on about it. Having Gladstone live here 130 years ago does not make the house breathe.”

The estate used to be quite feudal in its attitude, explains Charlie. “My father was born in 1925 and the world was very different then. I have a strong belief in the value of places, of estates but they have to make themselves as relevant as they humanly can to a wider community in order to survive.”

When Charlie took over, that wider community in Flintshire was in economic distress: “The late 70s and early 80s were a brutal time with the decline of industry, such as the closure of Shotton steelworks, with thousands and thousands of people having their livelihoods wiped out at a stroke.”

The estate workforce when Charlie Gladstone started running things was very small, numbering some 15, employed in traditional estate trades. That’s now more than quadrupled. “We employ a lot of people, about seventy full time and, at its most, about a hundred. Not everyone will love what we do but essentially it’s hospitality, culture and the great outdoors.”

The hospitality side includes renting out the former Head Gardener’s house as well as a very spacious and funky apartment in the West End of the castle. The Gladstones were kind enough to invite me to stay and left a key near the front door.

The dining room has a fine view over the medieval Hawarden Old Castle. In the modern one there is art everywhere, modishly mixing pop and abstract images with oil paintings such as Franz Snyder’s “Boy With Dog” and stiff family portraits. So you get Turner prize winner Jeremy Deller’s art prints alongside arrays of china figurines and witty juxtapositions of Mona Lisa reproductions flanking family members rendered in oils.

Charlie Gladstone explains: “I’ve tried to bring women into that side of the house because men have dominated the narrative here. The house belonged to Catherine Glynne. William Gladstone married her and because of the way we use surnames it became the Gladstone House, so I tried to reclaim that. When I moved into our side of the house the front hall had seven portraits of first-born men, including a giant one of John Gladstone who was a vicious slave trader. So I took them all down. I put John Gladstone’s one away.”

One of the artists whose work is present in Hawarden is the British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare. Charlie Gladstone explains: “He’s best known for his slave ship in a bottle on the fourth plinth in London’s Trafalgar Square. I’m very keen that we acknowledge in our family that a lot of our power and money came from the slave trade and we want to turn that into as much good as we reasonably can.”

Three years ago, Gladstone travelled to Guyana from Britain in the company of five relatives to offer a formal apology before an audience at the university, telling them, “It is with deep shame and regret that we acknowledge our ancestors’ involvement in this crime and with heartfelt sincerity, we apologize to the descendants of the enslaved in Guyana. In doing so, we acknowledge slavery’s continuing impact on the daily lives of many.” They also established a charity in the Caribbean country and called on the British government to formally apologise for its part in slavery and commit to reparations.

One of the other artists very much present in the castle is photographer and Academy award-winning costume designer Cecil Beaton. He was one of the quintessential Bright Young Things, described by academic Helen Rees Leahy as folk who “Took parties very seriously. The craze for fancy dress ball, pageants and masquerades demanded the most creative and extravagant costumes.” The always impeccably dressed Beaton could certainly deliver the style but he also liked to get away from the public gaze by retreating to Hawarden, where his niece Rosamund, know as Baba lived. Charlie Gladstone explains “He died when I was sixteen and I inherited a lot of stuff of his because my grandmother who lived in Hawarden was his sister. He took himself off into the stratosphere and pioneered some notions of queerness.”

A visitor learns about Beaton via notes handwritten by Charlie, pointing out Beaton’s design for My Fair Lady on Broadway above the kitchen sink and telling us how Beaton’s sister Baba was his first model and constant muse. Or pointing out how dressing up can liberate, transform or transgress. All this info is delivered casually and chattily, unlike, say the info panels of a museum.

Charlie Gladstone is keen to underline that this is not a house trapped in aspic and the estate is similarly forward looking: “Our families, the Glynnes and the Gladstones have been here for 500 years so there is a generational care. But you have to move with the times. We’ve built an elaborate network of footpaths in the woods that we own and there’s lots of access for locals. We’re running the pub, the farm shop – we have organic land this side of the road – and non-interventionist orchards. We have the Walled Garden School of craft and wellness. Most of the house is solar powered. Some of the parklands were rewilded before rewilding was invented. We are trying to be as gentle as we can.”

Charlie believes “They all help make Hawarden a better place to live and that has a benefit for the high street, which is quite vibrant at the moment but equally it gives me an economic reason to do up the things that need doing up. We also run an event called Summer Camp which grew out of a festival called The Good Life which we ran for ten years with Cerys Matthews, deliberately embracing Wales and shouting about Wales.”

William Ewart Gladstone was keen that his beloved books should stay in Wales, so he founded St Deiniol’s Library, in the heart of Hawarden village, helping to physically move some of 30,000 books from the study he called “The Temple of Peace” to the new building. With the help of a valet and one of his daughters the octogenarian Gladstone would personally trundle books up the hill, using a wheelbarrow to do so. All that amateur lumberjacking must have kept him fit.

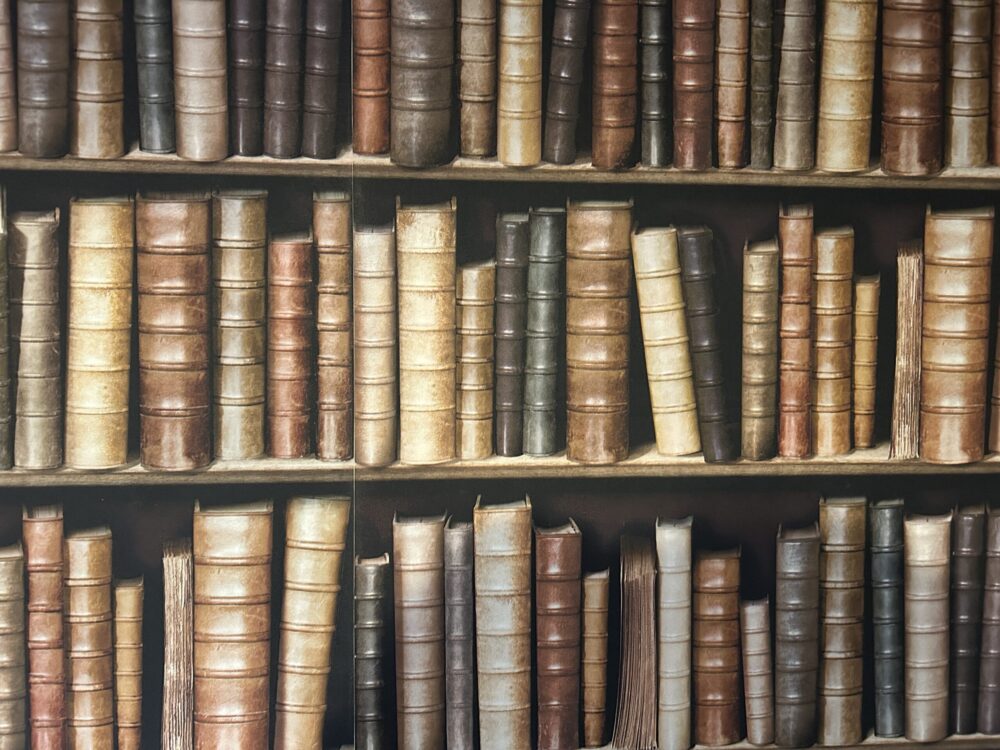

Gladstone had even devised his own cataloguing system for books, many of which which he busily filled with annotations. He wrote “On Books and the Housing of Them,” a volume that delves into the importance of books, their physical presentation, and the challenges of housing an ever-growing collection. His was certainly growing, as evidence suggests Gladstone read a book a day, with subjects ranging from mathematics to classics and history. As he once said: “Books are delightful society. If you go into a room and find it full of books – even without taking them from the shelves they seem to speak to you, to bid you welcome.”

The current Gladstone Library is a Grade I listed building, raised in 1902, designed by John Douglas and funded by public subscription. It is the UK’s only residential library where readers and scholars can not only study some of today’s total of 120,000 volumes but also stay overnight. Even the wallpaper in the bedrooms is bookish.

The library isn’t just a place to read. Over the years it been a quiet factory of new books, with some 300 written by authors given the space and silence to generate the words. In a magazine article, its current Warden, Andrea Russell gently hummed its praises: “Being in an environment where learning is seen as being a norm, where asking questions of yourself, of others, of the books you’re reading isn’t seen as being odd. People who want to talk about what they’re studying gives me real hope. There are times when you think, my goodness me, I don’t know what we make of any of this, but that there are people here who want to genuinely have conversations with people who they would not necessarily agree with, that all gives me hope.”

Gladstone’s original idea of a live-in library connected very much with his deeply-held Christian faith. The library sits cheek by jowl with the parish church of St Deiniol’s. Here William Gladstone devoutly attended a service every day when he was resident in the village.

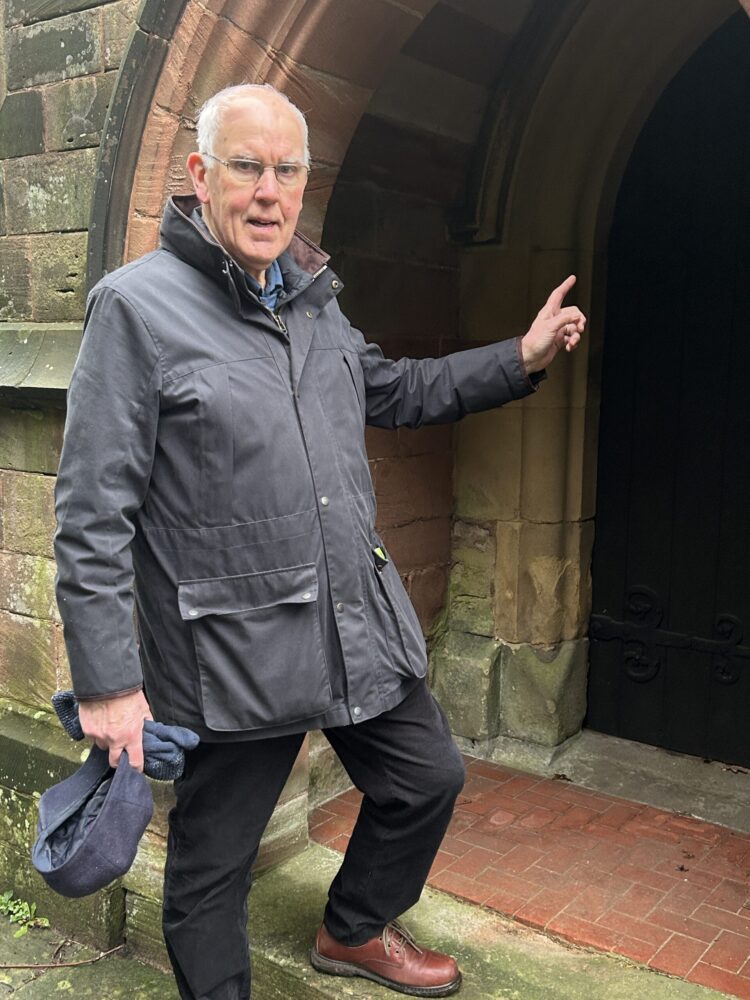

My enthusiastic guide is church warden Gareth Jones, who moved to Hawarden in 1976, working as an apprentice at what was then the British Steel Corporation’s Shotton Works, which employed 11,000. He eventually became a senior manager before retiring after 43 years service and shares Gladstone’s fondness for St. Deiniol’s. Gareth explains “There has been a church here since the sixth century, when the saint planted his staff here. Gladstone even had his own porch and entrance. The carriage would bring him to a special, dedicated door, separate from the rest of the congregation.”

Gareth guides me around the many fascinating features of St.Deiniol’s. They include a memorial by the Gladstone family to one of their servants, Sarah Jones, who ran a busy orphanage in a building on the estate. There are some striking stained glass windows, designed by the Pre-Raphaelite Edward Burne-Jones, who was a friend of Gladstone’s and often stayed at the castle.

Another window, the Armenian window, was gifted in gratitude for Gladstone’s trenchant speeches about the Armenian massacre. St Deiniol’s also has effigies of Gladstone and his wife, lying in “the boat of life” – even though their bodies are actually interred in London’s Westminster Abbey – as well as the funeral bier which transported his coffin on his final journey.

One of the other notable church features is Gladstone’s own translation of his favourite hymn into Latin. One of its verses easily suggests the appeal of Augustus Toplady’s work for this incredibly hard-working politician: “Not the labour of my hands/Can fulfil Thy law’s demands;/Could my zeal no respite know,/Could my tears forever flow,/All for sin could not atone;/Thou must save, and Thou alone.’

For a man so besotted with words, and so intelligently aware of the power they can exert when properly employed, the hymn seems to capture Gladstone’s ethos of hard work as well as the simplicity of his Christian faith. Just as surely as his own words can still resonate loudly, perhaps especially now: “Nothing that is morally wrong can be politically right.” You can say that again.

Jon Gower is Transport for Wales’ writer-in-residence. He will be travelling the breadth and length of the country over the course of a year, reporting on his travels and gathering material for The Great Book of Wales, to be published by the H’mm Foundation in late 2026.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.