Making tracks: Llanelli

Jon Gower goes on a personal journey to his home town.

In the Welsh poet Owen Sheers’ “Flag” he suggests that ‘A rail journey westwards is a good place to start,/The country can rewind or fast forward, depending on your seat,/Throws up sightings which get more frequent,/As the train nears the sea…’

I myself am on rewind, taking the train from Cardiff, where I have lived since the early 1980s, to my childhood home in Llanelli.

The stations and sights are achingly familiar. Bridgend’s acres of industrial units. The dune system at Kenfig, where a medieval town lies buried under the sand. The steel plant at Port Talbot. Neath station where my mother took the train westwards to start her marriage.

The memory of the Baglan Bay petrochemical plant at night, all silver pipes and gases flaring like a demonic fairy castle.

As we cross the river Loughor, entering my native Carmarthenshire, small flocks of little egrets rise up, birds from warmer climes that simply weren’t there when I was growing up. We pass Trostre tinplate works, a reminder of the fact that, before the end of the nineteenth century, Llanelli was virtually a single industry town, earning it the nickname Tinopolis.

When I was growing up the station announcer at Llanelli was a man whose nickname was Eddie Lip. My favourite story about him told how, one day, the train on platform one was coming in to platform two and vice versa. Eddie duly advised the waiting passengers: ‘You over there, come over here: you over here, go over there.’ You can imagine them all paralysed by the instruction.

In the age long before computers Eddie would have all the information written down on a piece of paper.

I was on the platform the day he dutifully read what was in front of him, announcing that the train to London would be stopping at ‘Gowerton, Neath, Port Talbot, Bridgend, ditto, ditto, ditto, ditto and London Paddington.’

My father worked on the railways – for British Rail as it was in those days – and loved it. He started off as a tea boy, working his way up through the ranks until he became a traffic supervisor.

In the single photo I have of him in those days he’s swapped a blue collar for a white collar and is therefore not wearing a cap like his colleagues.

My uncle Derek, too, was a railwayman, working as a shunter, so we were a railway family: my brother Alun and I, along with our cousin Carl were Llanelli versions of the railway children.

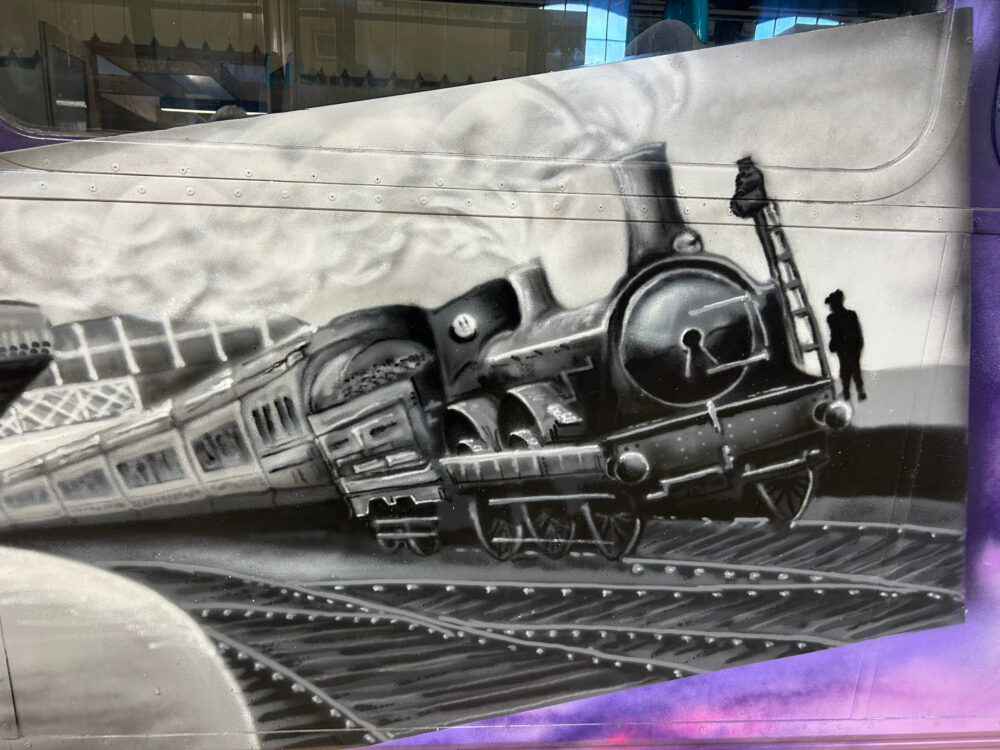

The train into Llanelli follows the line created by the greatest railway engineer of his age, namely Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

In 1833 he was appointed chief engineer of the Great Western Railway (GWR) but he had greater aims than simply constructing a line from London to Bristol. His idea was to extend the line into Wales, to Abermawr near Fishguard, thus providing a much-needed link to both Ireland and New York.

Brunel was the very definition of Victorian ambition.

Birdwatching

I have a small walk-on part in this railway’s history. When I was a boy I used to go birdwatching near my home in the village of Pwll, which often took me alongside that self-same railway line.

One day I saw that a storm had washed away the sea-wall, leaving the railway tracks dangling in the air. So I rushed home to tell my dad who sped to the nearby phone box, rang someone who in turn stopped the train.

Disaster was duly averted. I was given an award by British Rail, who presented me with a copy of The Collins Field Guide to British Birds in the Brunel-style sheds you pass as the train slows down into Llanelli station.

It’s a space which had recently been revitalised and transformed under the aegis of the Llanelli Railway Goods Shed Trust, a charity intent on creating a vibrant community hub.

Restoration

The first phase of the restoration was completed in 2022, as refurbished office blocks became teaching spaces and shared office areas while the second phase involves restoring the main hall.

This now houses a busy café while a preserved train, which adds an evocative atmosphere to the place, has multiple uses, including housing Caban Eco. community wardrobe full of reasonably priced clothes as well as free books and DVDs.

Paul Barrett is the Heritage Officer for the project. He explains how the GWR undertook an extensive programme of infrastructure investment in the 1870s, with proposals for the rebuilding of both the Railway Station and the Goods Shed at Llanelli appearing in the early 1870s.

Paul paints a picture of what was a very busy place in its heyday. From 1875 to 1912 onwards it employed up to 100 people, this at a time when tin-plating in the town had earned it the nickname Tinopolis.‘Out in the yard there’s a steel-framed building. It’s listed as a meal shed, for agricultural produce, animal feed and things like that, but local people also knew it as the banana shed, as fruit was ripened there.

Loading ramp

More exotically there’s a loading ramp in the yard and people remember circus animals being offloaded there.’

Paul further explains how ‘At the far end of the steel frame canopy they built a small shed which they called the valuable goods store. I understand they used it for the storage of cigarettes and beer and wines and spirits for a short time.

‘Because in the early years of the last century, there was a bonded warehouse nearby.’ It was run by Margrave Brothers who blended and bottled spirits, including the Excelsior and Pearl whisky brands, at the rear of their building at the corner of New Dock Road and Trinity Terrace. ‘So, there are stories about, you know, cigarettes and spirits and even cash being stored in the valuable goods store.’

Before the goods shed became fully derelict it was home to the local permanent way team, housed in Portacabins outside. The team was responsible for the upkeep and repair of the railway tracks and attendant infrastructure.

Track man

Clive Peckham worked on the P-Way for ten years, starting off as a track man in 1979, when he was 24 years old. It involved hard graft, working as a basic labourer who was part of a ten-man gang, overseen by a ganger. They covered a patch from Llandeilo Junction, near Llanelli to Swansea Loop West, just outside Swansea High Street station.

The work was very physical: ‘Changing sleepers, flat bottom rails, bullhead rails, and lifting the rails up with the jacks, so that the jack was underneath the sleeper.

And then you’d shove all the ballast in between, and then pack it underneath the sleepers to raise the track.’ It was hard graft and also dangerous work: Clive sadly recalls a good few fellow workers losing their lives or having terrible accidents.

Eventually Clive became a track chargeman, working in the office. In those days you could use the train network for delivering railway mail: ‘When I used to do all my correspondence – sick returns, timesheets and so on – I used to take all of it over to Llanelli station, put it on the train, give it to the guard, who in turn gave it to Alexander House in Swansea, which was a big block, like a skyscraper near the station.’

Let’s now walk to the end of Station Road to what used to be the three cinema screens of Theatr Elli.

Across the street used to be a doctor’s surgery. One half of one of the most successful and quintessentially English comedy duos, Flanders and Swann – who gave the world such classics as “Mud, Mud Glorious Mud” and “The Gasman Cometh” – was born in Llanelli and his father worked as an assistant to a Dr Davies in this surgery.

Penniless

It is quite a story. Donald’s father, Herbert fell in love with Naguime Sultan Piszova, a Muslim from the desert beyond the Caspian Sea. Having arrived penniless in Tilbury Docks Harold was offered work in Llanelli, living in Coleshill Terrace. Here he was later joined by his brother Sokolik, a devout Russian Orthodox who liked to entertain people by playing the balalaika and performing Eastern dances involving whirling sabres and knives.

After Dr Beeching took his axe to stations all over, following the publication of his report ‘The Reshaping of British Railways’ in 1963, Donald Swann wrote quite the loveliest song about the long list of stations that were closed as a result. “The Slow Train” is essentially an elegy, a litany of lost halts and countryside stops.

As the song tells us: ‘No one departs, no one arrives, from Selby to Goole, from St Erth to St Ives. They’ve all passed out of our lives. On the slow train.’

Swann’s song was a literal swansong for such arrival and departure points as Littleton Badsey, Openshaw, Long Stanton, Formby Four Crosses and Cockermouth. It serenaded, or, rather, said sayonara to the stops at Audlem, Ambergate and Dunstable Town; name-checking Pye Hill, Chittening, Cheslyn Hay and Windmill End and so many other places with richly evocative names such as Dog Dyke, Tumby Woodside and Trouble House Halt.

While Swann elegises English stations in the main, Dr Beeching’s cut deeply into Wales as well. Imagine a time when you could get to the abbey at Strata Florida by buying a ticket to, well, Strata Florida Halt which served the villages of Ffair Rhos, Pontrhydfendigaid and Ystrad Meurig.

Nearby Caradog Falls Halt served those who lived in the hamlet of Tynygraig and any visitors who wanted to visit the waterfalls of the same name. All sorts of places were thus connected and made accessible.

When the Welsh language short story writer Kate Roberts wished to visit the remote lake of Llyn y Fan Fach she could catch the train to Craig-y-Nos Station at Penwyllt Halt in what is now Bannau Brycheiniog and walk on from there.

Opera diva

This station was financed by the world-famous opera diva Dame Adelina Patti who lived in Craig-y-Nos Castle in the valley below. Among her many famous guests who alighted here was the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, (they were rumoured to be lovers.)

From 1903 onwards, there were three trains a day stopping here, on the line between Brecon and Neath. You could easily get to Swansea by changing at Colbren, while there was also a light tramway to carry stone from the area’s quarries using steam locomotives, including one called Emily moving the heavy material.

Penwyllt Halt was just one of a total 189 stations in Cymru felled by Beeching’s axe, on top of the 166 stations already set for closure pre-Beeching’s report, such as St Asaph. From Arthog to Resolven, Llanfyllin to Wolf’s Castle, rural stops were lost. Entire lines were mothballed such as the Ruabon to Barmouth line.

These halts and stations connected locally and took people into a much bigger world if needed. I remember the Abertillery artist John Selway telling me how you could go to the ticket office in nearby Llanhilleth and buy a return ticket to Lisbon. You could travel from Garneddwen to Glasgow, from Beaver’s Hill to Barcelona, from Arthog to, I guess, Vladivostok if you really wanted to go from the south of Gwynedd to south eastern Russia.

It is therefore heartening to see the prospect of some new stations opening in Wales, putting green and sustainable travel options in place.

Jon Gower is writer-in-residence for Transport for Wales. He will spend the next year travelling the country by train and bus, writing regular features for Nation.Cymru and researching The Great Book of Wales to be published by the H’m

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

A tremendous article -diolch yn fawr John Gower. For someone who remembers pre-Beeching travel – in my case particularly travelling from Cardiff to Ruabon and tben down to Llangowerhalt for an Urdd holiday in Glan Llyn, it evokes pure nostalgia!

What a wonderful insightful article – thank you ‘muchly’.

Paid anghofio Llangower, John.