Making Tracks: Machynlleth

Jon Gower

In A Machynlleth Triad the travel writer Jan Morris suggests that Machynlleth, known by locals as Mach, “seems to stand there beside its river thoughtfully, perhaps just a little cynically, watching the world go by: just the place, if one wishes to explore the character of Wales itself.”

“It’s this weird finger of Powys border county poked between Ceredigion, Gwynedd and Meirionnydd,” explains Mike Parker, author of On the Red Hill, a book about his home, Rhiw Goch, six miles out of town. “That’s what gives it its flavour: it’s a border town in the middle of Cymru Cymraeg. It is where the mountains of the north bump gently into the small rolling hills of the south: it’s where the hill farmers of the east look out to the sea to the west.” To add to town’s significance, he says: “The clock in the town is the fulcrum, the omphalos of Cymru.”

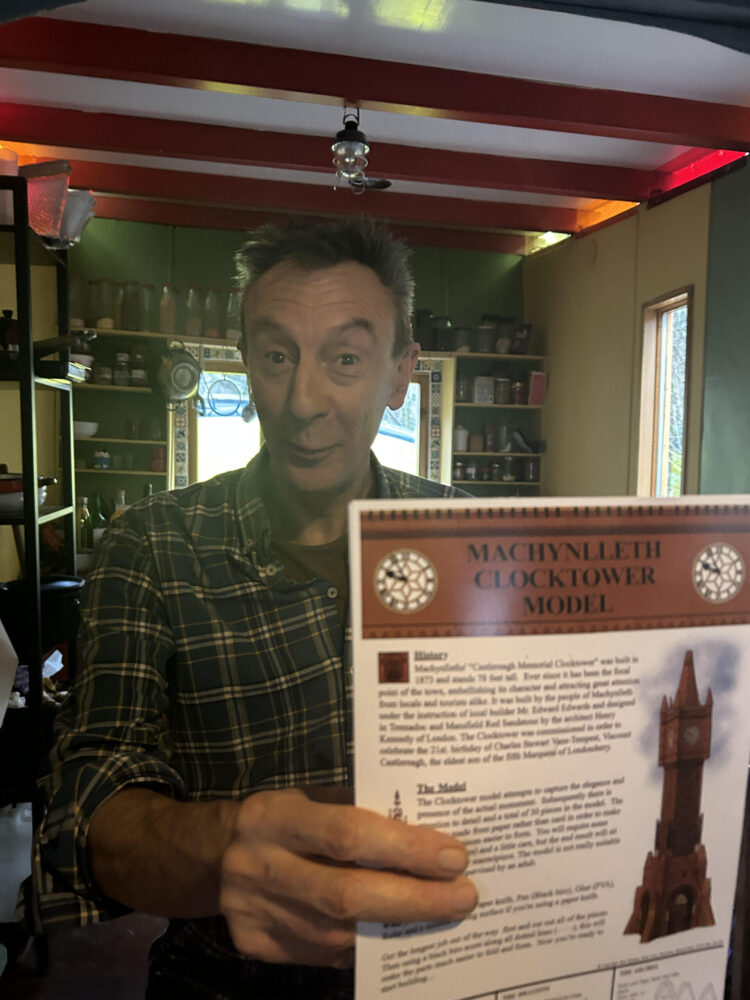

The 24 metre high clocktower was built by the residents of Machynlleth to celebrate the coming of age of the eldest son of the Fifth Marquess of Londonderry, who lived at Y Plas in the town.

Rob Nicklin knows it most intimately well as he’s created a model of it. It’s very ornate, as he explains: “There are pipers, lute players and four dragons, one on each corner, plus the architectural frills on the arches.” Having painstakingly studied it he wistfully suggests “I should have done Big Ben because it would have been a better seller!”

One of the town’s most famous buildings is Owain Glyndŵr’s Parliament House on Heol Maengwyn, the main drag. Although the current building likely dates to a time after Glyndŵr, it is still synonymous with him, as his Parliament regularly convened here following his crowning as Tywysog Cymru, Prince of Wales in 1404. The poet and writer Angharad Penrhyn Jones, who works in the bookshop there, can sense his presence: “I feel personally connected. This is what people do with Glyndŵr. I work here in the Senedd-dŷ. I feel his spirit, I do, it’s hard to explain. It’s possible that he never set foot here, it’s all conjecture isn’t it, there’s so much myth but I feel his presence.”

Angharad considers it a privilege to work at the Senedd-dŷ, in part because of “The incredible vision set out in the Pennal Letter.” This was sent to Charles VI, King of France requesting assistance for help in Glyndŵr’s rebellion against English rule. “He worked with the heavyweights in law who had been working in Rome. This was not a rag tag bunch of guerrilla fighters but the elite in Europe – learned, experienced people, so he had a solid plan, unlike politicians today.”

Angharad briskly stokes the logs on the fire, a welcome sight on a crisp January day. “Part of my job is to keep that fire going and it feels symbolic. Often people come here from a long away. People with Welsh roots from America, they hold their breath when they come in, they get really moved and become tearful. They’re sensing something here and that’s really lovely. He really does capture people’s imaginations: it’s extraordinary to see.”

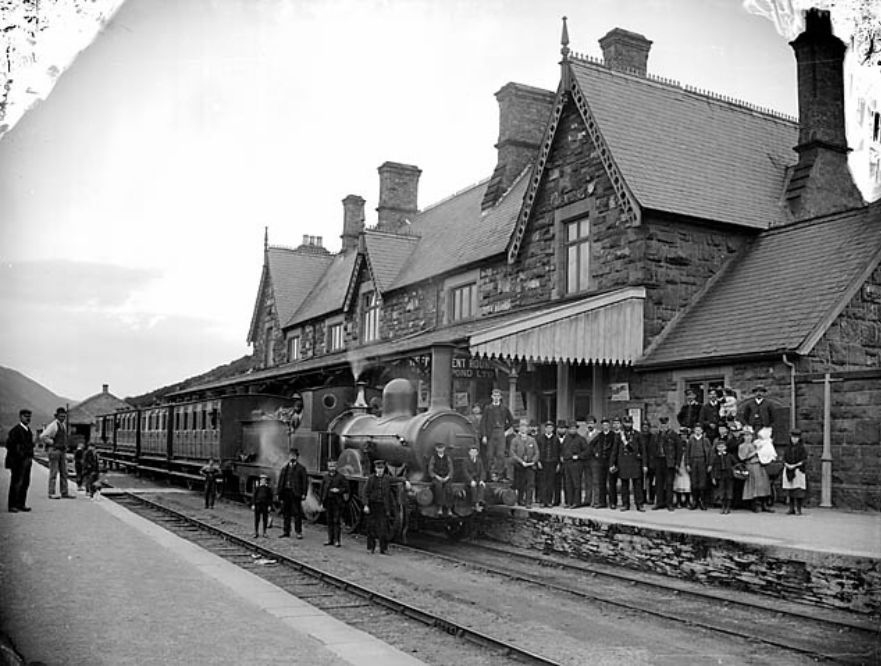

The population of Machynlleth swelled by nearly a third in the 1860s and 1870s because of the arrival of the railway. Keith Gunstone, recently retired as a conductor, saw the complement of the staff increase considerably in recent years too: “To some forty five drivers nowadays and nearly as many guards. The train divides at Machynlleth. I used to spend ages walking through the carriages making sure people had the correct info but I’d also make jokes about the stations. ‘We’re now approaching Newtown – Newtown, so good they named it twice – just silly little things. Alight here for Welshpool International Airport.” Keith remembers pulling into Harlech where a group of Americans thought it wonderful they had built the castle right next to the railway!

Elwyn Jones worked for 18 years in Mach station’s ticket office. One of Elwyn’s responsibilities was organising replacement transport should a train break down or if there the track was under water. “Up to four times a year the track would be closed due to flooding – it would be on the Newtown to Welshpool stretch or there’s a little bridge just up from Machynlleth, where a tributary runs into the main river,” reminding us that both the river and the railway are formative features of the town.

Someone who knows the river like the back of his fly-fishing hands is Paul Morgan who came to work here as a water bailiff in 1978 and did so for forty years. He now runs Coch-y-Bonddu – leading international dealers in books on angling, game shooting, sporting dogs and falconry. Paul explains the name: “Coch-y-Bonddu is the small red-brown beetle that hatches on bracken on the high hillsides generally in June, that has been represented by a fishing fly for a hundred and fifty years. It’s well known and I chose it as a shop name because it’a Welsh fly that is known to trout fishermen.”

Selling books sounds a lot more sedate than his previous job as a bailiff: “Catching poachers was the main part of the job. We were full time after a loose gang of ten or a dozen people from the area who were poaching all day, every day. We then started to get an influx of gangs from other parts of the country. It started with the development of monofilament nets which are invisible in the water. They were setting nets at night and initially they weren’t too careful.”

Paul enthuses about his favourite book, Fishing in Wales, by Walter M. Gallichan, published in 1903. This is full of angler lore and sage advice, not least concerning sewin on the Dyfi: “It is the slow travellers that leisurely explore the pools, and make frequent halts on their journey, that are most often tempted. Pool-locked sewin, after a considerable sojourn in fresh water, are usually wary until put off their guard by colour in the river or the shades of evening. In sewin-fishing it is always well to watch the twilight hour.”

Paul tells me that sea trout catches on the Dyfi have declined enormously in the past fifty years but points out that the 1880s there were no fish at all in any of the southern tributaries of the Dyfi because of pollution from the lead mines at Dylife and Llanbrynmair. “The rivers ran yellow as there were no settlement tanks so the crap all went straight down the river. So up until around 1900 there were virtually no fish. The Ystwyth was dead. The Leri near Talybont was dead.’ Things changed hugely. “By the time I came here in the 70s the river was absolutely bloody heaving with fish. And the bigger pools in summer: you stood above them and there would be a fish in the air all the time.”

Film-maker Pete Telfer, who lives in the nearby village of Ceinws, is a passionate art lover. For him The Museum of Modern Art, in the former Wesleyean Tabernacle chapel, is one of the town’s great cultural assets. The museum’s story starts with Owen Owen, a local draper whose family had lost all of their money because of gambling, a story much repeated in the Welsh countryside. Pete explains that “Owen Owen was a skillful businessman who opened up the very first department store in Liverpool, which eventually extended into a chain. This allowed him to buy back the lost estate and put money in trust. This allowed Andrew and Ruth Lambert to buy the Tabernacle. I don’t think they’ve been properly recognised. If you count the wall space it’s bigger than funded spaces such as Oriel Davies or Aberystwyth Arts Centre.”

In addition to MOMA the town of 2000 inhabitants has no fewer than five bookshops. One of them is Pen’rallt run by Diane Bailey and Geoff Young, who hail from Essex and Aberdare respectively. Diane agrees that there is a high ration of bookshops per capita, especially as there were no bookshops selling new books when they moved to the town fifteen years ago. Diane “Doesn’t like the idea of people coming here to find something that is caught in aspic, that’s caught in the past, so I don’t sell people the standard town histories, because they’re so out of date. We do sell a lot of The Rise and Fall of Owain Glyndŵr. People are interested in how something comes into being and then disappears.”

The books in the window at Pen’rallt range from books about Nina Simone and poet Linton Kwesi Johnson’s memoirs to one about Irish Wolf Men and Water Hounds mixed with Welsh language titles such as Holl Ganeuon Dafydd Iwan and Stori’r Iaith. This mixture chimes with one of the ideas about a future Wales aired in A Machynlleth Triad where Jan Morris imagines a day when “Those who declare themselves Welsh, and are prepared to honour the Welsh language and culture, are Welsh.”

One way of honouring the language is to learn it, so I chatted with two learners, Ian Richards who lives in Tre’r-ddol and Anne Marie Carty who lives in Ffwrnes.

Ian’s father was a Welsh speaker from Cwmafan in south Wales but Ian was brought up in Hornchurch in Essex. “I started learning seriously when I was 50. My relationship with Machynlleth has changed because of gaining the language. I love Welsh music – Steve Eaves, Sian James and Georgia Ruth and wonderful people like that – it’s a great way of becoming familiar with the language, learning the lyrics.”

When film-maker Anne Marie came here in 1992 she heard lots more Welsh on the street than you do now. “I quickly realised just how important the Welsh language was. I started to learn it and it’s taken me a long time but it’s literally been like a door opening into another culture.”

Ian and Anne Marie study Welsh under the tutelage of Rhiain Bebb who has seen many changes in the town. “There used to be a couple of bakeries, the butchers, we used to have a couple of newspaper shops but it is still vibrant. There’s the Comedy Festival, Gwyl Glyndŵr, Gwyl Pethau Bychain, there are different cultures who hold different events. It’s become a popular place, people want to live here.” In addition to being a Welsh tutor Rhiain is also a harpist, who in turn taught Cerys Hafana, who is currently reinventing the instrument for a young audience. I do the sums. One in a thousand people in Machynlleth is a harpist.

To help build bridges between different cultures Bethan Morgan has created a Welsh learners’ choir, harmoniously formed from people who want to want to sing with gusto in a second language. “There’s something about Machynlleth. Since the Centre for Alternative Technology started in the 70s it brought with it a certain kind of person – usually but not always English, educated or at least open minded, people who know the importance of working as a team or in the community. There’s an old fashionedness about making your own entertainment and people still do. It is quiet here, there is no cinema.”

Just as there is a high proportion of harpists in Machynlleth’s population so too are there poets and they can find their inspiration anywhere. I meet Pryderi Jones who has just been declaiming a poem in the bar of the White Lion. “I was here one Sunday afternoon with my friend Derek, watching the football. I noticed the big screen was like the stained glass window of Sky Sports, similar to the way people used to go to church with the apostles and angels and disciples and the supernatural beings and it seemed that people worship the football players on the screen.” Which duly inspired a poem.

Pryderi was reading his work in the pub as part of the Post Turkey Tango, a town-wide, day-long celebration of the arts in the town, in part designed to defy the post-Christmas, January blues. It’s the brainchild of musician Phil Wheeler’s, whose house is readily identified by the mannequin pianist playing in the front garden. I caught up with him just after he’d been singing a song in Hennighan’s chip shop about, well, chips.

Phil and his wife came to Mach forty years ago, suitably arriving in a VW van. “The welcome ever since has been amazing.” They had a dream of self-sufficiency, promulgated by John Seymour and Richard Mabey. “We wanted to come to the country to plant potatoes but then very quickly found out the farmer next door was selling a bag for a pound.” They nevertheless settled here and run a fabric shop and support the Post Turkey Tango, which underlines the wealth of creativity in the town. Or as Mike Parker put it : “You can’t buy a paper in Mach without a samba band accompanying you.”

“It is a creative hub, like-minded people gravitate here, with all the different shops that are open as well, so it seems like the perfect place to hold events and help young people build up their CVs,” explains Nadia Gillard. She helps run Sploj, a bilingual creative space in Machynlleth. “There are lots of youth centres set up for the younger generation but there isn’t that much going on for people in their twenties and in their thirties, even. Sploj was set up to open opportunities for them to be in lead roles, setting up workshops in things they feel passionate about. So we have ‘Ladies who mix,’ Clwb DJ and Queepo, which is a queer poetry group. There’s also a small cinema with a capacity of 30 which shows films from all over the world. We’ve got the projector and screen and some seats which we got from a doctor’s office.”

Machynlleth is also a town set in the countryside, so I visit writer Julie Brominicks in Pantperthog, a “bushy hollow” through which runs Nant Ysgolion, a stream stepped all the way up to a hidden gorge with a waterfall. It’s a very secluded spot, about three miles from Machynlleth. Julie tells me about their home: “It’s a tiny house. It’s on a trailer, so doesn’t have fixed foundations and so the footprint is very small. We’re off grid, which means we don’t have a lot of appliances and neither do we want them really.”

The view through the window of the tiny house is made up of grown-out hedge trees – blackthorn and hawthorn, some witch elm, sickly ash. The other side of Nant Ysgolion stand giant redwoods, frosted with green lichen. Julie enthuses about their looming presence: “Treecreepers like such places to roost. A band of long tailed tits comes through frequently like monkeys and goldcrests with golden blazes on their heads, coming lower down in the canopy in winter.”

In this hidden gorge Julie and partner Rob can bathe under the stars. “We have an old cast iron bath that we fill with cold water and then light a fire underneath. So you can stay in the bath on a cold winter’s night for an hour, watching the stars.”

One of the other magical aspects of the place is the presence of pine martens. You can almost intimate the mustelids in the thick woods. Says Julie, “They’ve been so successful since their introduction by the Vincent Wildlife Trust that people see them quite frequently. One lady almost ran one over on her bike.”

I suggest they are very motile mammals: “Yes, inquisitive, hyper-alert, rapid, always on the go. I did see one running across the garden once. It was fast, speedy, like a flame burst of orange – it had a much more of orange-coloured breast than I’d imagined. It was a flame-flash across the garden and then it was gone, just like that. When we first moved here fifteen years ago there were abundant grey squirrels, to the extent they were even chewing through the gas pipe. We haven’t seen a grey squirrel here for years and that definitely correlated with the advance of the pine martens.”

We enjoy an early morning stroll in marten country, through a lovely stretch of Celtic rain forest. Julie explains that, “The gorge gets narrow very, very quickly and is therefore steep sided so the air is moist throughout the year.” Little light that gets in but yet there’s enough for viridian carpets of moss to grow so thickly in places you can press your fingers in up to the wrist. Julie adds that “Polypodies and epiphytes grow on the trees, which is a sign of ancient woodland.” It’s a biodiverse stretch. Pied flycatchers nest here in summer, the males dapper in their tuxedo black and starched-white plumage.

Julie knows there are martens here because their images have been captured on camera. ‘We might just be on the edge of a territory. They’re solitary but their territories butt up against each other. We’ve definitely seen two young pine martens.”

During a snowy period Julie saw a marten’s tracks on the trunk of a storm-felled tree. “On the log itself there were these wide, solid footprints in the snow and it had clearly been bounding along – on the trees rather than on the ground.” It underlined the agility of the sure-footed mammal, able to bound along on slippery, snowbound tree boughs.

After I return home Julie sends me footage of a marten moving through the woodland, not far from where I slept. It slinks in from the inky dark stands of trees, inquisitive and uber alert. I duly add it to my bursting image bank of Machynlleth, Jan Morris’ town which she described as being very much “full of ghosts and fancies.”

Jon Gower is Transport for Wales’ writer-in-residence. He will be travelling the breadth and length of the country over the course of a year, reporting on his travels and gathering material for The Great Book of Wales, to be published by the H’mm Foundation in late 2026.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

I think Jan would curl her lip and say something like supercilious sais full of advice and terribly nice

Diddorol dros ben.. Edrych ymlaen at fwy o straeon.😊😊