Making Tracks: Remembering Llywelyn ap Gruffudd at Cilmeri

Jon Gower visits the memorial stone at Cilmeri on the weekend when Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, the Last Prince of Wales is commemorated.

Travelling on the Heart of Wales line seems appropriate when journeying to a place where the line of Welsh princes came to an end.

At Cilmeri, on December 11th 1282, the beating heart of the country was seemingly removed by a Norman sword.

I alight at Builth Road station, opened in 1864 where a terrace of houses used to be home to railway workers. You can also see the shell of the former goods shed, intriguingly once called Dartmoor as you look along the track in the direction of Llandrindod Wells.

Nowadays an average of 15 passengers use Builth Road station every day, although that number increases when there are extra trains and connecting buses during the week of the Royal Welsh Show.

But today is different, December quiet, and I am the only passenger getting off. Rural rush hour.

I stay at the Cambrian Bed & Breakfast where host Debbie Lang explains how the downstairs was converted from the station’s waiting room and buffet. She also tells me how two railways used to cross here in Llechryd: the Mid Wales Railway’s Llanidloes to Brecon Line, opened in 1864 and the Central Wales Extension Railway’s line from Craven Arms, now part of today’s Heart of Wales line.

The name later changed from Llechryd to Builth Road low level while the high level station lives on today.

The early 1920s was the high point of Builth Road’s fortunes. With 100 workers in the depot’s workshops, offices, stores, goods yard, engine sheds, two railway stations and signal boxes, it was probably the biggest employer in Radnorshire.

The B&B is chock full of railway memorabilia while the Christmas tree is decorated with rosettes. Debbie Lang proudly explains ‘We’re always showing our Large Black Pigs, one of the 12 rare breeds of pig.” I ask her what a judge looks for in a winning specimen. “They’re looking for pigs that seem to be standing on their feet as if they’re on high heels. The teats should be even and their ears should be down to the nose.’

I notice one, a model Large Black Pig, in the Christmas nativity crib in the shadow of the festive tree of rosettes.

When husband Dave joins us he asks me what I’m doing in the area: I explain that I’m attending the Day of Remembrance for Llewelyn in Cilmeri. He promptly explains how his dad, local builder Bob Lang helped erect the memorial in the village: “When they tried to set it in place, using a crane, they couldn’t quite get it to stop wobbling. So my father set a sixpence under one corner and fixed it.”

He later scattered his parents’ ashes at the memorial, thereby deepening the family connection.

The weekend’s commemoration were organised by the Cofio Llewelyn committee, chaired by Calfin Griffiths. He suggests that one motivation for arranging the weekend-long events is “the hiraeth, the longing for a prince to fight for Wales.” Some people attend year after year as it’s in their hearts but he wishes more people would join in. “Historians, school parties and so on. People visit Rome, St Davids, the summit of Yr Wyddfa. It would be good if some of them came to Cilmeri.”

Most of thirteenth century Wales was dominated by two native princes, namely Llywelyn ap Iorwerth and Llywelyn ap Gruffydd.

Their successful reigns suggested what the country could do if left to its own devices. Literature flourished in the work of Dafydd ap Gwilym, while the monasteries at places such as Strata Florida generated their most important chronicles.

Both princes lived in splendour in the wooden hall of their Anglesey court in Aberffraw but they also built castles such as Dolbadarn and Dolwyddelan, romantically situated keeps standing solidly in remote spots.

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Llywelyn the Last, was the most successful of the long line of Welsh princes, albeit for a short time, as was often the case in medieval times, when rulers often did not live that long.

While Henry III was at the helm of England he signed the 1267 Treaty of Montgomery which brought Llewelyn within reach of becoming the ruler of the whole of Wales. Indeed he was the first of the native princes to use the title Prince of Wales but also the last, coming up against one of the toughest medieval Kings of England, Edward I.

Edward I set an enormous trap for Llywelyn, a great pincer movement splitting his Gwynedd stronghold in two.

A fleet of ships sent up the Menai Strait cut Ynys Mon off from Eryri, where the mountains acted as a sort of rugged castle for Llywelyn. He escaped from there and headed south, intent on mustering new forces. But he fell into another trap when he was caught and killed, apparently at Cilmeri.

As with events so far back, facts mix freely with conjecture. Llywelyn seemingly became separated from his main army. Caught in a minor skirmish on the outskirts of the main battlefield he was killed by an English knight who didn’t know who he was.

The exact circumstances of his death have been lost to history and are unclear. What is clear, however, is that the English do not seem to have realised who they killed, possibly because Llywelyn was travelling incognito and not wearing a coat of arms.

His death was a lethal stroke of bad luck, while there are dark hints of betrayal which swirl around the story.

But death wasn’t sufficient humiliation. Edward I arranged to have his Welsh opponent’s head cut off to be taken and exhibited on London Bridge.

His body, meanwhile was interred at Abbey Cwm Hir near Rhayader. I went there once in the company of the great rugby player and Welshman Ray Gravell, a personal hero and occasional actor who would have made a brilliant Owain Glyndwr had we ever made a Welsh Braveheart.

I remember Ray and I stood above the very simple grave and wept freely, not saying a word as we both silently communed with the past, and pondered what might have been.

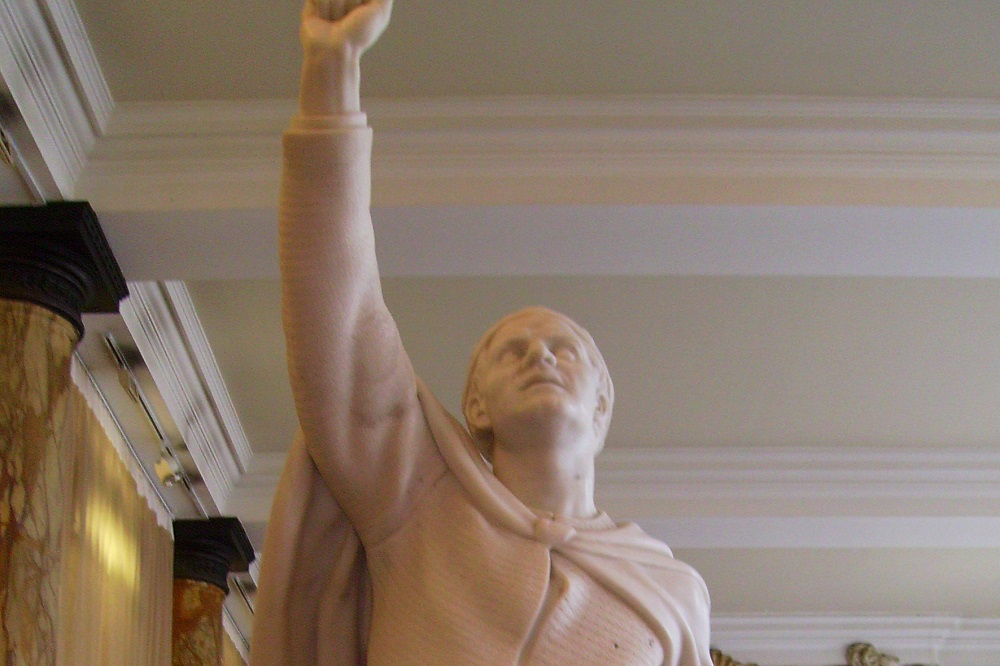

The Llywelyn memorial in Cilmeri marks the place at Cefn-y-Bedd where the prince fell on December 11th, 1282. and was initially a stone obelisk, erected in 1902. This was replaced in 1956 by a block of granite (from Trefor quarry in Llywelyn’s native Caernarfonshire) embedded in a plinth set on a low mound.

A local legend was kept alive as a story told by his father to Steve Morgan as a boy. “Llywelyn approached the local blacksmith in Aberedw, asking him to put the shoes on his horse the wrong way round so pursuing knights couldn’t follow him in the snow. But the knights press ganged the villagers and got out of them how they’d shod the horses and that’s how he was caught.”

Tradition has it that Llywelyn heard mass before meeting his death and so the day of Remembrance started formally after tea in Cilmeri Community Hall with a service at the out-of-the-way St Davids Church in Llanynys, which sits astride a field on the bank of the river Irfon.

Here Canon Rev. Mark Beaton officiated in three languages – Welsh, English and Latin – and delivered a sermon in which he explained that as he imagined the slaughter that day he also “saw God’s arms carrying the dead and the dying, those who earlier in the day had troubledly worshipped on this site.”

At the far side of the monument grounds, a steep path leads to a set of steps down to the well where Llywelyn’s head was washed.

The well is now protected by a metal cover, but you can lift the cover and expose the water beneath.

Behind the well is a slate slab inscribed in Welsh and English with the phrase, ‘Legend has it that this is the well wherein the head of Llywelyn ap Gruffydd was washed’.

Llywelyn’s head was sent to Rhuddlan for Edward’s macabre pleasure and thence to London. It was displayed as that of a traitor and paraded through the streets, crowned with ivy in mockery of the ancient Welsh prophecy, which said that a Welshman would be crowned king of the whole of Britain (which happened when Henry Tudor became King in 1485). The head of Llywelyn, it is said, was still on the Tower of London some 15 years later.

Gareth Jones, Secretary of the Owain Glyndŵr Society told me how Llywelyn’s death played into the later story of Owain Glyndŵr: “Some hundred and twenty years after Llywelyn’s death Glyndŵr’s uprising started amid growing unrest. One of Llywelyn’s descendants, his great nephew Owain Llawgoch, threatened to return from France, where he was fighting for the French against the English, to proclaim himself Prince of Wales but he was assassinated before he could do so.

Owain’s flag, featuring four lions rampant, was similar to the House of Gwynedd as he was the last desendant. Glyndŵr then took it as his own coat-of-arms.”

Llewelyn managed to unite much of Wales under a single ruler and in so doing contributed to the emergence of Welsh national consciousness. His loss was described as a cosmic one in a famous elegy by his own court poet, Gruffudd ab yr Ynad Goch, who asked.

According to Rhisiart Dafys, who read it at the Llanynys service it “was written at the time, so tells us how Llywelyn’s followers felt at the time, an outpouring of emotions, where the stars fall out of the heavens.”

Thou great Creator of the world,

Why are not thy red lightnings hurled?

Will not the sea at thy command

Swallow up this guilty land?

Why are we left to mourn in vain

The guardian of our country slain?

No place, no refuge, for us left,

Of homes, of liberty, bereft;

Where shall we flee? to whom complain,

Since our dear Llywelyn’s slain?

It left a country bereft. At Cilmeri an inglorious ambush was an unheroic ending for a leader who was just beginning to build a country.

Jon Gower is Transport for Wales’ writer-in-residence. He will be travelling the breadth and length of the country over the course of a year, reporting on his travels and gathering material for The Great Book of Wales, to be published by the H’mm Foundation in late 2026.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

As the English Prince of Wales/Outsiders is rightly phased out, we need to increase the importance of remembering Llywelyn as well as Owain Glyndwr. The last English investiture pantomime may have been well over half a century ago, but the remnants of that are still visible in Caernarfon. We now need more than a layby, information plaque, stone, for the real people of importance in our history.

I attended Cilmeri this weekend an enjoyable and thought provoking series of events. My thanks to the organisers and in particular the Cor Cochion Caerdydd who sang at the church service in Latin and at other events. It is a pity some of our so called national leaders do not attend this important national event. People from Yes Cymru did attend and local Liberal Democrat MPs and MSs are frequently there. Sadly the local pub the Prince Llewelyn was not open. For many years this pub has provided refreshments for visitors and had music and entertainment in the evenings. I… Read more »

All of our schoolchildren should be taken to Cilmeri to witness the site and to hear about our history. Sadly, if you mention Llywelyn (and Glyndwr) to many of our teachers and Heads they wouldn’t have a clue who you were talking about.