Making Tracks Up the Rhondda

Jon Gower learns about coal, community and Corona pop on the Treherbert line.

If you want to get to know an unfamiliar place it’s often best to befriend a native guide. Luckily for me the writer and TV producer John Geraint is a great friend, and the author of Up the The Rhondda! was happy to join me for Transport for Wales’ equivalent to time travel, pretty much every station offering a quick history lesson.

The hour-long journey from Cardiff brought back floods of memories, not least the sight of the weir at Radyr. Every time John and his mother Margaret would pass this landmark, or, perhaps this rivermark, she would always point it out: “The white water at Llandaff tumbling down. Mam was always absolutely determined to point this out, each and every time we passed it.”

John’s wondered ever since why his mother was so very insistent and thinks that it might be because it demonstrated that river water could be clear and white. In those days Rhondda river water was jet black, clogged with thick layers of coal dust.

In his book Up the Rhondda! John vividly recalls being with his mother at Tonypandy and Trealaw station: “I can still see the chocolate-and-cream-coloured signs, the little Booking Office up at the level of Bridge Street, the steep, steep steps down to the platforms. Yes, two platforms in those days, And three tracks: Up and Down and the middle line for coal trains. A siding for goods too. Just like the proper railways I’d read about in… Thomas the Tank books.”

John’s mam, Margaret was the daughter of the blacksmith in the Naval colliery in Penygraig, where the Cambrian Combine dispute or the Tonypandy Riots started. She would occasionally go shopping to Cardiff, to the great department stores, David Morgan and James Howells, and sometimes take John with her, pointing out “what was the longest platform in the world” at Pontypridd as they went. She would also explain how, during one of the downturns in the pit, John’s grandfather came to work in the chain works, Brown Lenox in Pontypridd. Here they prouduced the heavy anchor chains for the Royal Navy for over a century, as well as manufacturing those needed for suspension bridges and for the great ocean liners, including, finally, those for Cunard’s QE2 before the company pulled up the anchor when the manufacturing site closed in 1999.

John’s schoolteacher father, David John Roberts, would travel on a branch line which no longer exists, being the Ely Valley line, which went up to the Cambrian colliery in Clydach Vale. “This had a passenger service which started in Penygraig station and came down through Tonyrefail, joining the rest of the network at Llantrisant. His first teaching post was in Llanharry. So he would take this small passenger service. If ever he was late on a schoolday morning they would hold the train at Penygraig for him until he turned up, so that’s personal service isn’t it?”

John remembers the names of the stations between his home and Cardiff as if they were a mantra. “Tonypandy, Dinas, Porth, Trehafod, Pontypridd, Treforest, Treforest Estate, Taffs Well, Radyr, Llandaff (for Whitchurch) and then there was no Cathays so it was straight down to Cardiff Queen Street and then, of course, Cardiff General as it was then known. Going north from Tonypandy there was Llwynypia and then there was Ystrad station. Ystrad station was in Tonpentre until Transport for Wales finally sorted it out and created a station in Ystrad and renamed the station at Tonpentre. Before that it must have been confusing for anyone wanting to go to Tonpentre because they had to go to Ystrad, or if they were aiming to go to Ystrad they ended up in Tonpentre!

“I’m a good old Rhondda mongrel and I like the fact that we have two languages here. We’re just coming to Gelli and there were two farms here, Gelli Galed and Gelli Dawel, so Hard Copse and Quiet Copse, which sounds like the formula for a long running police procedural series. My home address was Tylecelyn Road, Penygraig, Tonypandy, Rhondda. Tylecelyn is, of course, Holly Hill. Penygraig you could translate as Rock Top. Tonypandy is interesting because it means ‘the meadow of the fulling mill’ – a fulling mill was where the treated the wool from the sheep, beating it to make it waterproof.

“And then there’s the Rhondda itself – there’s a long dispute about the name’s derivation – but one form of it is ‘babbling brook vale’ and I do quite like that because we do babble a lot in the Rhondda.”

On the subject of water, John remembers travelling on the train on summer days to visit Ponty Pool, the swimming pool which preceded the lido on the edge of Pontypridd’s Ynysangharad Park. “As an extra treat, we would deliberately get on the wrong train and have a free ride all the way up to Merthyr. When we were challenged by the conductor we would feign confusion about being on the Treherbert train. And so we would get the great delight of seeing another valley through the windows of a train.”

Through the windows of our train we see the next station stop, Trefforest estate, which was one of the first industrial estates in Wales. Its origins lie with the formation of the ‘South Wales and Monmouthshire Trading Estates Ltd.’ in June 1936. This was a non-profit making company whose aim was to establish one or more trading estates in Wales to diversify employment, and provide some alternative to the coal and steel industries which were in decline. “It was part of that attempt to create employment in the Depression of the 1930s,” John informs me before the train moves on.

Trefforest next, where backpacked students alight for one of the campuses of the University of South Wales. The university has its roots in the coal measures. Local industrial leaders came together in 1913 to form the South Wales and Monmouthshire School of Mines.

It served the coal mining industry that dominated the South Wales valleys and was owned and funded by major Welsh coal owners. It was renamed the School of Mines and Technology in the 1940s, training young coal workers and also army cadets. Some wags later referred to it as the School of Minds but there is a rather lovely truth to that. This became Glamorgan Technical College in 1940, a Polytechnic in 1970, the University of Glamorgan in 1992 and the University of South Wales in 2013, after the University of Glamorgan merged with University of Wales, Newport.

“It’s interesting,” says John, “because of the connection with the intellectual life of the miners.” He tells me about a very interesting experience he had on a train at the end of 2025. “I’d come up to Pontypridd to visit a friend and I was going further north on the train to Treorchy. The train was packed and the only seat I could find was opposite a young man who was reading a five hundred page book, full of little yellow flags marking important passages. I was leaning across, trying to find out what he was reading and it was The Philosophy of Plato. By this stage we were coming in to Tonypandy and I said that’s very interesting what you’re reading because there’s another fascinating book with connections with Tonypandy. H.V.Morton, the travel writer who wrote In Search of Wales and broke the story of Tutankhamun’s tomb and basically invented travel writing with that book said, as he travelled through Wales: ‘On a street corner in Tonypandy I met a group of miners discussing Einstein’s Theory of Relativity.’”

The miners’ thirst for knowledge and interest in the events of the day was expressed in the miners’ halls and libraries, the latter built and stocked with money that came from weekly contributions. John reckons they are “One of the glories of the valleys and it’s wonderful to see in the Rhondda Fach, the Tylorstown Welfare Hall getting a major grant to restore it.” Along with, say, the Parc and Dare Hall in Treorchy it’s a cultural expression of the miners’ lives, “with a penny deducted from each pound of their wages to pay for such things.”

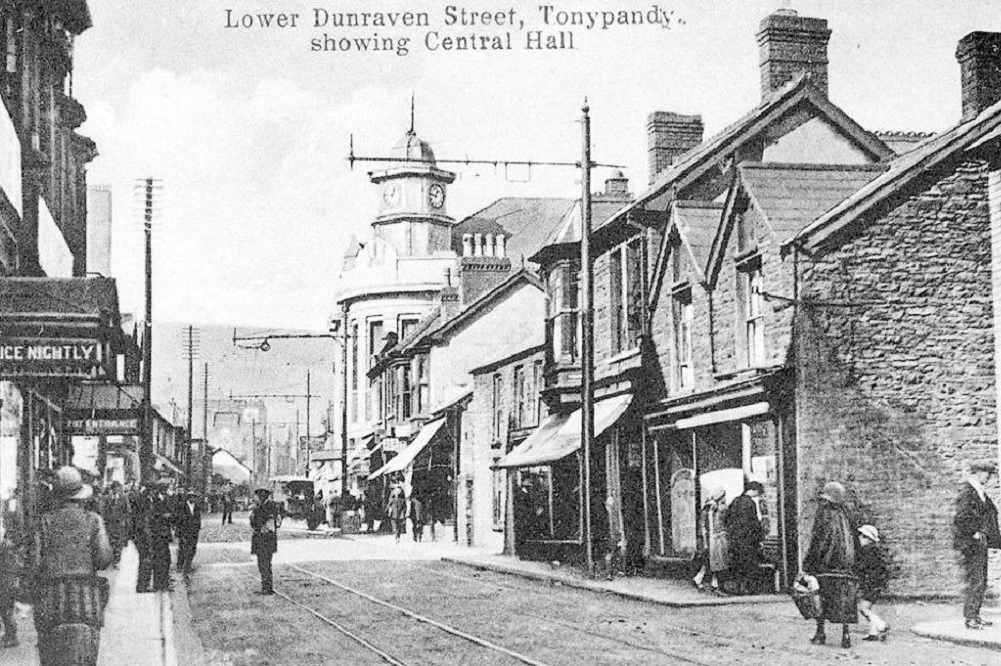

John suggets “The other glory is the chapels, the non-conformist chapels in the Rhondda. Just up the road from Tonypandy station used to stand the Central Hall, Tonypandy, a Methodist church and power house of radical ideas, of a social gospel, of a men’s parliament as it was called, a mock parliament where they debated the great issues of the day. They had all kinds of social outreach such as a workshop for the unemployed, and that again was a vital expression in the 1930s of people’s determination not just to survive but to thrive in the circumstances in which they found themselves.”

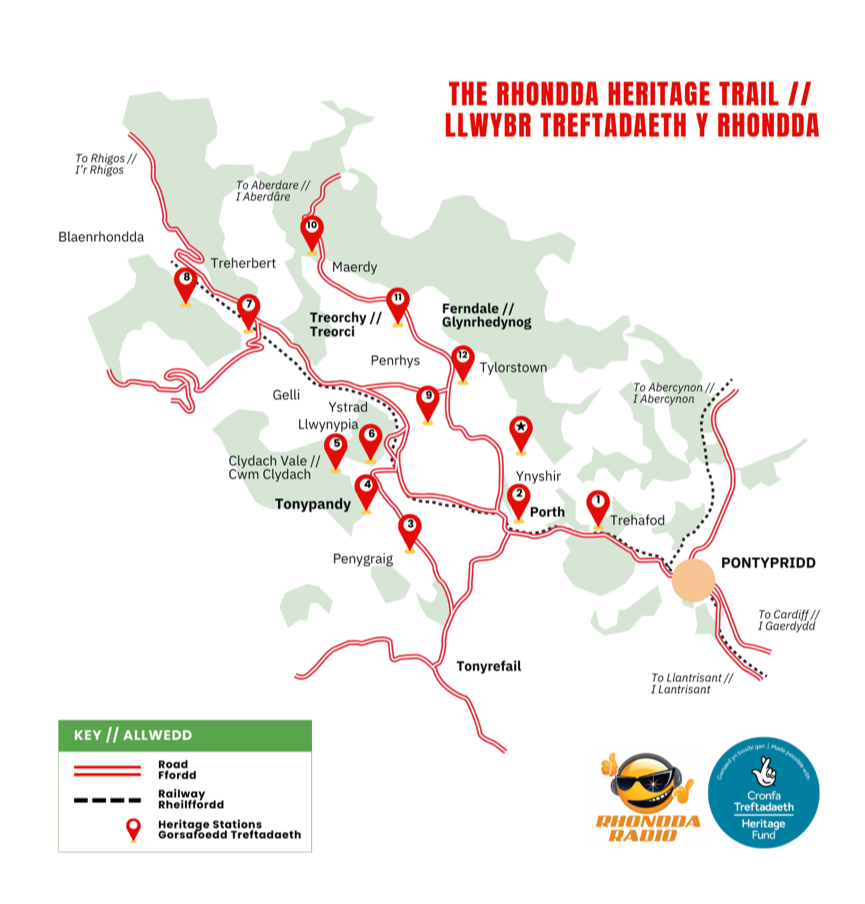

Through Pontypridd and on to Trehafod, where you can experience The Welsh Coal Mining Mining Experience pretty much at the end of the platform. It’s also the start of the Rhondda Heritage Trail, part of a physical trail through both of the Rhondda Valleys, with information stations along the way.

John explains how “You can walk to the Rhondda Heritage Park where the trail effectively begins with an information station at the old Lewis Merthyr Colliery.” John’s grandfather was a faceworker there and he was determined not to send his son down the mine – a typical story – but he always said “That if he had his days over again he would do nothing other than work underground with his butties. There was that camaraderie, that sense of belonging to a team, to colleagues and work mates was enormously special.”

Out of the window, on the left hand side as we travel northwards we can see the stack of Lewis Merthyr colliery, still standing. The stack is about 170 feet tall and John was told by a former miner called Ivor England, who worked underground there, that the depth of the seams in that colliery were ten of those stacks deep, so if you look at the height of that, and imagine ten of them on top of each other, you get down to the level they were cutting coal. Lewis Merthyr was one of no fewer than 79 pits in the Rhondda.

Soon we’re in Porth where I encourage John to repeat my all time favourite Rhondda story and he duly obliges: “There was an amazing, entrepreneurial grocer called William Evans who, along with another grocer William Thomas set up a chain of local grocers’ shops in the valleys, known as Thomas and Evans.

“One day Evans was in his headquarters in Hannah Street in Porth, just a few yards from the railway station – in fact by that stage Thomas and Evans had their own railway sidings to import goods directly into their warehouse, they were turning over so much.

“An American walked in who was clearly down on his luck, in fact he was starving. He claimed to be a medicine man who’d been run out of Galveston, Texas at the point of a gun. He offered William Evans, in exchange for the price of a good, hot meal, ‘the secret of making carbonated water the like of which your customers will never have tasted’ and that was the genesis of Corona pop.”

Eventually William Evans built a factory in Porth, which we pass on the railway line, where they manufactured the marvellous carbonated water. Evans hit upon the idea during the Depression, when money was tight, of taking door-to-door deliveries of this pop around. So the Corona man would knock on your door and it was very hard to say no to a treat being delivered to your doorstep, proof of Evans being a very shrewd businessman. In its heyday Corona had 200 salesmen in south Wales, each driving a horse and cart.

John explains how “The pop was originally known as Welsh Hills Mineral Waters, which wasn’t thought to be a marketable name when the business expanded to Birmingham and widely in southern England as well. So William Evans instituted a competition for his staff to come up with a new marketing name for the pop and a grand prize of five pounds would be awarded to the winner. When the committee Evans had appointed from among his senior staff said they’d chosen the name Corona, Evans said in that case I will keep my five pounds because it was his own entry.”

Corona Pop was one of the delights of John’s childhood, especially dandelion and burdock flavour, which took its place alongside orangeade, limeade, cherryade and American cream soda. They hit peak production at the end of the 1930s when a staggering 170 million bottles were being sold each year. Then they invented sub brands – Tango was one of them – which is still going. Eventually Corona was bought by the Beecham group but despite a fantastic advert in the 1970s, in which the head bubble proudly maintained that “every bubble’s passed its fizzical” it eventually succumbed to the greater marketing power of Pepsi and Coca Cola.

Porth station has another of those really long platforms, where Thomas and Evans had their sidings. When John Geraint was at Porth County Grammar School in the 1970s “We had a very interesting art master called Alan Warburton, who used to do murals and on this station platform he created what was said to be the longest station mural in the whole of Britain. It told the history of the Rhondda and the railways here complete with images of the very modern Intercity 125.

“Alan Warburton was quite a character and just around the corner from here there was one of Rhondda’s famous urinals, and he created a mural on the bricks facing the road, which was soon was dubbed a ‘murinal’.

“In the hot summer of 1976 Prince Charles came to visit this murinal. There had been a hosepipe ban in place for weeks because of the long, long drought. The murinal had not been washed down for weeks if not months and I happened to be working in a petrol station right next door to it, and my shift started at half past six in the morning. On the day that Prince Charles arrived it was stinking to high heaven but within ten minutes of my shift starting a tanker of water from the council arrived and hosed the whole place down with as much water as could have supplied a whole Rhondda street, in case the Prince’s nostrils were offended.”

On to Dinas Rhondda and then Tonypandy which prompts the question ‘why are the riots here as famous as they are?’ John avers that it’s because “This was a pivotal moment in the history of the South Wales Miners’ Federation and in industrial relations in Britain. The miners’ leader, ‘Mabon’, William Abraham, was a person who was very effective in his own way but he was very close to the mine owners such as D.A.Thomas who became Lord Rhondda.

“Mabon regarded Thomas as a friend but there was also a younger generation of much more radical union leaders who came to prominence in that dispute. And because Winston Churchill sent in the troops to quell the riots it became a cause celebre and, importantly, led to the writing of The Miners’ Next Step by Noah Ablett. This was a famous pamphlet, published in 1912 which prophetically saw what might happen even if the mines were nationalised, that it would put the miners into conflict with the state.

“If you look at the industrial disputes of the 1970s and 1980s, the one in 1984 in particular, you can see how far-sighted and prophetic in many ways those miners were. They could see that the miners should have control over their working lives. They knew how to work the mines, were hands-on at these difficult seams and knew all the dangers and about the physical labour of extracting the coal. They were the ones who should have been directing how the mines were run.

“They argued that leaders were always becoming corrupt, no matter how well intentioned they were: ‘No man should have such power at his disposal as true leadership implies’ they said in that pamphlet. So they were far ahead of their times but they became the leadership themselves, of the miners across south Wales.

“It was a pivotal campaign, a pivotal dispute in that regard. And it didn’t just go on for just two nights of disturbances in Tonypandy, it was fifteen months before the miners went back to work. That shaped the attitudes of many, many people in these valleys towards the mine owners and eventually led, one might argue, to the nationalisation of the coal mines after the Second World War.”

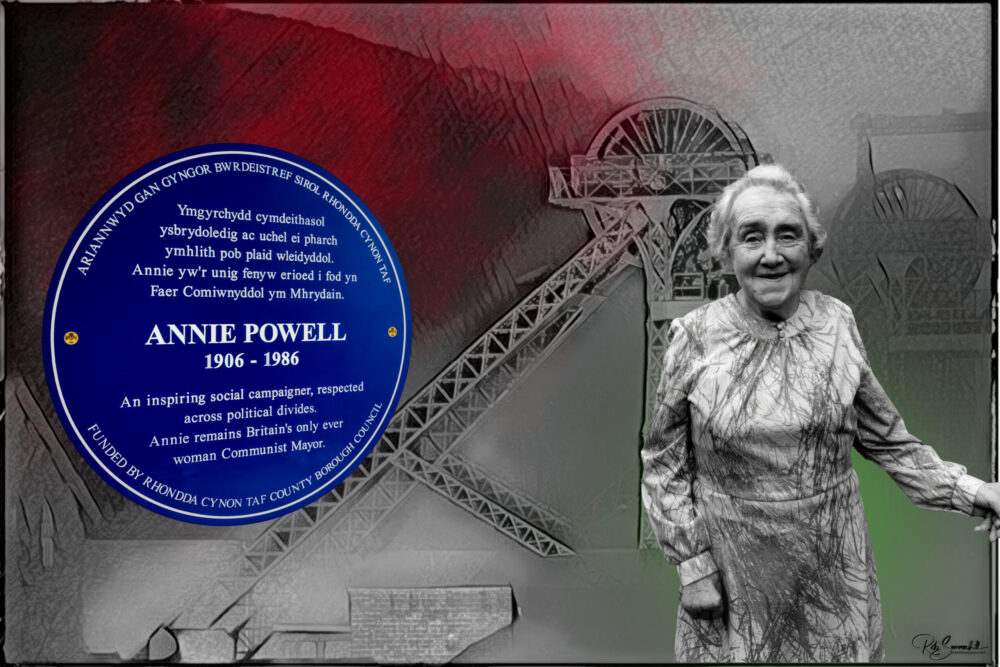

As the train arrives in Llwynypia we see the long line of terraced houses built alongside the tracks. This is Railway Terrace, where Annie Powell lived, the first woman Communist mayor in the whole of Britain, “achieved through the force of her intellect and force of personality,” suggests John. Powell was the councillor for John’s ward in Penygraig, so he cast his first democratic ballot as an eighteen year old in her favour and she topped the poll. “Of course she did, because she was a fantastic and tireless worker for the people here and she took up the cudgels for them, as she put it. And I would visit her and her husband Trevor. When I became interested in the history of the Rhondda my mother arranged for me to go and have tutorials with Annie. She had a real grasp of history, was steeped in Rhondda history but she also had this commitment to a broader cause. She was very interested in the Welsh language, a fluent Welsh speaker herself.

“She didn’t however tell me the famous story, possibly apocryphal, about how, as part of a delegation to Moscow in the 1960s she taught Nikita Krushchev to sing “Hen Wlad fy Nhadau.” She also had sheer dogged determination. It took her several attempts to become a local councillor and she stood in parliamentary elections as well, at a time when there was a sizeable communist vote in the Rhondda. In the 1945 election Harry Pollett came close to taking the seat for the Communists. When I caught up with her many years later and her rheumatism had become very pronounced, particularly in her hands “and she showed me her clawed fingers, Well John she said, my hands are pretty bad but my tongue’s all right.’ She had that steel but she also knew how to work with people. She was a fantastic local councillor who would take up the cause of anyone who was being mistreated by their landlords, or would take up the cause against the intransigent bureacracy of the welfare state.”

Annie Powell was a local politician of national renown and international outlook. To understand Rhondda’s connection with the rest of the world you could do no better than climb Penygraig Mountain, suggests John: “Carn Celyn was the name I knew it by. It’s not very tall, about 1400 feet but still a steep climb up from Penygraig and you can see a lot of the Rhondda from there.

“I was always told that if you stand at the trig point, where the trigonometry stone stands at the top of Carn Celyn and you proceed in a direct line east on the cardinal point of the compass you have to travel across the lowlands of Gwent, north of the Cotswolds , across the flatlands of England, across the North Sea, through Holland, vast swathes of Germany before you’re ever standing that high again and by that stage you’d be in the Ural Mountains. And likewise, if you go due West directly from that point you cross the rest of south Wales, across southern Ireland, across the whole Atlantic Ocean and Eastern Canada and you’re standing in the Rockies by the time you’re as high as that again.

“If you stand up there with your arms outstretched on those two cardinal points of the compass, left and right, east and west, you have a sense of reaching out to the whole wide world and that is also something that is also true about the Rhondda and its history, I think: that we weren’t just an inward looking, narrow people in a narrow valley, we had this sense of internationalism, we were a people involved in a world wide struggle.”

Jon Gower is Transport for Wales’ writer-in-residence. He will be travelling the breadth and length of the country over the course of a year, reporting on his travels and gathering material for The Great Book of Wales, to be published by the H’mm Foundation in late 2026.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Absolutely.brilliant,it brought ma y a tear.to this 76 yr old guys eyes.