Part One: Remembering the Tonypandy Riots

This week marks the anniversary of key events in the Cambrian Combine Dispute of 1910.

This is the first of three special articles about the ‘Tonypandy Riots’ by John Geraint, author of ‘The Great Welsh Auntie Novel’, and one of Wales’s most experienced documentary-makers.

‘John On The Rhondda’ is based on his popular Rhondda Radio talks and podcasts.

John Geraint

‘It’s that time of year again’, as the Stereophonics put it. Early November. We’ve put the clocks back. But imagine… if we put them back much, much further. Imagine…it’s early November 1910.

12,000 mid-Rhondda miners are on strike. From Porth to Ystrad, every colliery is at a standstill. Negotiations with the coal owners have broken down. There’s no knowing when or if they’ll resume. And then something happens that turns this industrial dispute into something else again, something almost mythical.

Not just a battle for who controls the conditions under which the miners labour, hundreds of feet below the Rhondda, to dig up the Black Diamond – and the power and wealth it represents. No, this is also a battle for the kind of place that, above ground, the Rhondda will become, the kind of lives that Rhondda people will lead.

It’s a clash of massive forces. On one side, the Chief Constable of Glamorgan, the Metropolitan Police, the Lancashire Fusiliers, the 18th Hussars and Winston Churchill.

On the other, those 12,000 mid-Rhondda miners and their families. It’s going to be a Riot.

A new history

Fourteen years ago, a BBC documentary which I produced and directed, ‘Tonypandy Riots’, made the news. It marked the centenary of the Cambrian Combine Dispute.

The film looked back from 2010 through the eyes of four local people – singing star Sophie Evans; Penygraig rugby player Derwyn Nicholas; Tonypandy College community manager Julie Atkins; and ambulance controller David Gwilym Jones.

We had expert help from other Rhondda people – historian David Maddox, miner Ivor England and the Chief Constable of South Wales, Peter Vaughan.

The whole programme was built on the foundations of a lifetime’s academic research and thinking about what happened in 1910 by another son of the Rhondda, Professor Dai Smith, a friend and colleague of mine for many years.

We thought of our project as ‘A New History’. We closed the streets of Tonypandy for a few hours so that hundreds of 21st-century schoolchildren could be filmed marching in the footsteps of their great-grandparents.

We showed them and the watching viewers exactly what happened in 1910.

But why? Why does what happened so long ago matter? Why has it echoed down the long decades since? And what does it mean for us now?

Big questions, important questions for what the Rhondda has been, for what it is. Indeed, for what Wales could be, will be.

Upper five foot

Dunraven Street, Tonypandy, 1910: a retail paradise built to trade on the wealth that Rhondda coal has generated: milliners, drapers, flannel merchants, outfitters, ironmongers, shoe and boot shops, all the latest fashions. Tonypandy has a whole class of shopkeepers – they’re big cheeses.

One of them is more than that. Willie Llewellyn the chemist played for Wales in the legendary win over the 1905 All Blacks. He’s a hero to everyone locally.

But not all the shopkeepers are loved. Some of them own the terraced houses where the miners and their families live – and they lease them on condition that the miners spend their wages in (you’ve guessed it) the very shops they own.

Ah, those wages.

How they’re paid is crucial to what happens. The miners don’t get an hourly rate, a weekly wage or a monthly salary. They’re paid according to the weight of sell-able coal they can cut.

Getting the coal isn’t easy (if it was, anyone could do it). It sits in thin seams, sandwiched between hard, useless rock laid down millions of years ago. Digging it out takes huge physical effort. And once the most accessible coal is won, the miners have to go to places where the bands of rock have faults, where there’s stone mixed in with the coal, where the groundwater floods in.

The crunch comes at the Ely pit in Penygraig, over the price per ton that’s going to be paid for work on a new seam – the Upper Five Foot. Everybody knows it’s going to cause problems.

Mabon

But this isn’t just about pounds, shillings and pence. It’s about a young generation of miners’ leaders, about their vision of a better way to run their industry – indeed their whole world. They’re impatient with the old-style miners’ agent, William Abraham, ‘Mabon’ to give him the bardic name he liked to use.

Mabon believes in co-operating with the mine-owners. But there’s a new breed of mine-owner – tough, modern, business-minded. Step forward D. A. Thomas, soon to be Lord Rhondda.

Thomas merges mid-Rhondda’s pits into a single company, the Cambrian Combine. He’s determined to flex its industrial muscle to drive down costs. In other words, lower wages.

Across the summer of 1910, deadlock: the miners in the Ely pit won’t accept the new rates. So on September 1st, D. A. Thomas shuts the colliery gates against them, putting them out of work. It’s a lock-out.

Miners in the other mid-Rhondda pits come out in solidarity, but Mabon scolds them back to work: they’ve no legal basis for striking without notice. So the union lodges serve that notice – a strike on November 1st.

Mabon isn’t finished though. He’s close enough to D.A. Thomas to get him to cough up a little more: “My friend D.A. Thomas has been suffering from poor health; and I feel sure that on his holiday in France he will not benefit… if he were to hear of a strike such as this.”

The Power House

Mabon’s compromise is resoundingly rejected by the men. And now the owners dig in. They refuse point blank to talk further. So on November 1st, all of mid-Rhondda’s miners come out on strike.

Thomas isn’t worried: he’s made a deal with the other coal-owners across South Wales. They’ll indemnify the Cambrian Combine against its operating losses, however long the strike goes on. Thomas can sit and wait until the starving miners have had enough.

When word gets back to the Strike Committee, they realise that their only chance of winning is to hit the Cambrian Combine hard and fast where it hurts – in its assets. If maintenance work can be stopped, D. A Thomas’s pits will be at risk of damage by flood and rockfall, forcing him back to the negotiating table.

So on November 7th, summoned by bugle, marching behind the Tonypandy Fife band, miners and their families – thousands of them – tramp from pithead to pithead, stopping the machinery that keeps the collieries ticking over.

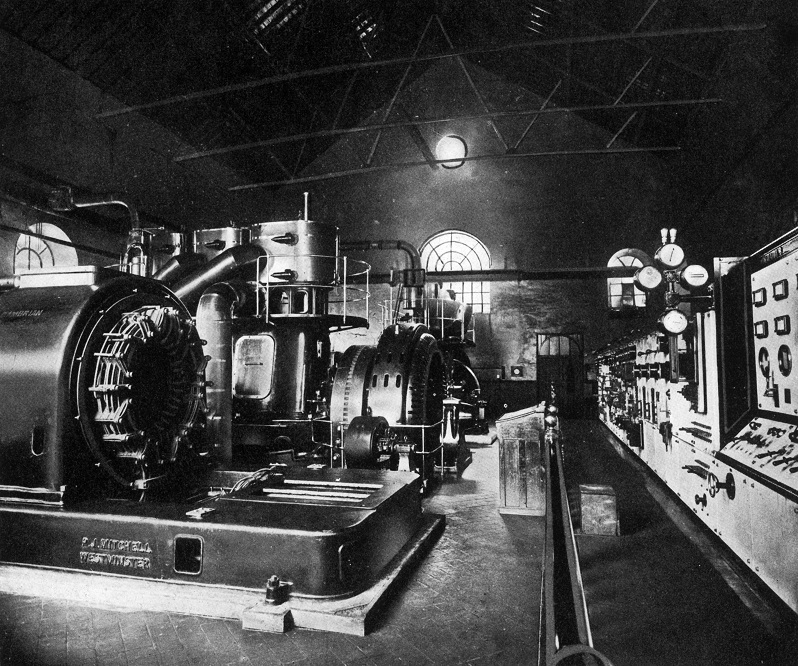

Fires are raked, boilers and ventilating fans shut down, electric generators silenced. There’s little opposition until they arrive at what we used to call the Scotch Colliery, on Llwynypia Road. Here stands the citadel the owners have chosen to defend, a symbol of their property-owning rights – the colliery’s Engine House, the Power House.

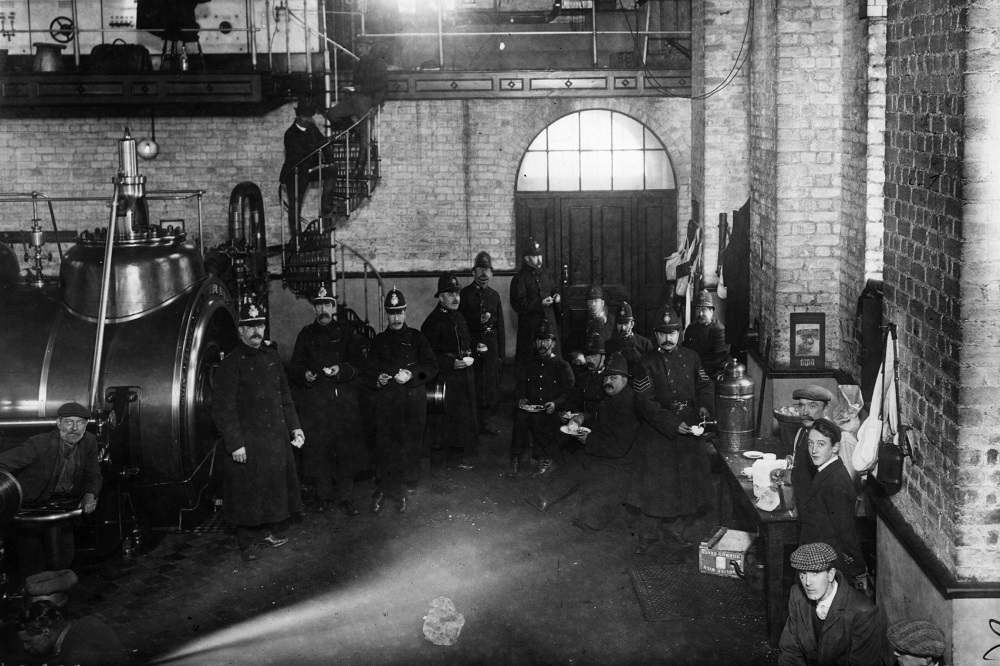

It’s literally a power struggle. The police are here. The Chief Constable, Lionel Lindsay, a good friend of the coal-owners, has mustered every officer he can find.

Underground: three hundred pit ponies, deliberately left down there by the owners, though there’s been no work since the strike began. These mute hostages may drown, deep in the flooded roadways, if the electric pumps are shut down.

But if that happens, D. A. Thomas reckons that public opinion will turn against the miners.

Troops

At the colliery gates, the miners demand to speak to the maintenance crews inside, claiming their rights of peaceful picketing. The police refuse. The stand-off gets tense.

At 9 o’clock that evening, there’s a change of shift inside the Power House. Youths try to rush the police guard at the gateway. Will John, the miners’ leader, appeals for calm from what’s now a huge crowd.

But stones are thrown. The police charge. There’s hand-to-hand fighting. The miners are driven back to Tonypandy Square. But there, well beyond midnight now, they continue to defy the police.

The Chief Constable, terrified that he’ll lose control completely, telegraphs for the troops to be sent in.

The next installment will be published tomorrow.

You can listen to much more Valleys history in the Rhondda Heritage Hour every Wednesday afternoon at 3pm on Rhondda Radio: https://www.rhonddaradio.com/

The latest edition of the Rhondda Heritage Hour – including John Geraint’s account of the Tonypandy Riots – is available to listen to on demand here: https://www.mixcloud.com/RhonddaRadio123/rhondda-heritage-hour-6112024/

‘Up The Rhondda!’, John Geraint’s collection of exuberant and evocative essays, is available here: https://www.ylolfa.com/products/9781800994874/up-the-rhondda!

And John’s coming-of-age novel set in the 1970s has recently been reissued as ‘A Rhondda Romance’: https://www.cambriabooks.co.uk/product/a-rhondda-romance/

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

DA Thomas was a Welsh speaker I believe.