Part Three: Remembering the Tonypandy Riots

This week marks the anniversary of key events in the Cambrian Combine Dispute of 1910. Here’s the final part of three special articles about the ‘Tonypandy Riots’ by John Geraint, author of ‘The Great Welsh Auntie Novel’, and one of Wales’s most experienced documentary-makers.

‘John On The Rhondda’ is based on his popular Rhondda Radio talks and podcasts.

John Geraint

Tonypandy 1910: armed soldiers are patrolling the streets. They’ve been sent in by Home Secretary Winston Churchill, despite his assurances that he’d hold them back.

Churchill has intervened in a dispute between 12,000 mid-Rhondda miners and D. A. Thomas, the coal magnate who owns the Cambrian Combine. Alongside a detachment of Metropolitan Police, the soldiers’ presence is preventing picketing, allowing blackleg labour to keep the Combine’s assets – their pits – in working order.

Outgunned, the miners are losing the battle – but who will win the war?

In 2010, I produced a BBC documentary, ‘Tonypandy Riots’. We made the news, closing the streets, so that local children could be filmed processing in their great-grandparents’ footsteps, and holding their own mass meeting in the middle of Dunraven Street to pay tribute to them.

“We gather here today,” they said, “to remember the Rhondda’s coal industry on the centenary of the Cambrian Combine Dispute of 1910. We think of all those who were affected by that dispute and of everyone associated with our long and proud history of mining.”

“We are mindful that the true price of coal was the sacrifice made and the hardship endured by the miners so that others could enjoy warmth and power. We are grateful for their vision and determination that the riches of the world we live in should be shared fairly by all of us.”

Anger

In 1910, Dunraven Street is where the colliers vented their anger against the coal-owners, the shopkeepers, the government. But now that the troops are here, the miners can’t stop D. A. Thomas using blackleg labour to keep his pits ticking over.

He can wait and wait and wait, indemnified against his losses by other coal-owners, until the toll on the miners’ families becomes too much to bear. It takes ten long months, but eventually, hungry and still angry, the men are forced back to work. All their efforts seem in vain.

Those going back to toil in the Ely pit’s difficult Upper Five Foot Seam won’t earn a ha’penny more for each ton of sellable coal they cut than D. A. Thomas offered before the strike began, in the compromise brokered back then by his ‘friend’, the old-style miners’ agent William Abraham, ‘Mabon’.

A million pounds has been lost in wages. And for a quarter of the mid-Rhondda workforce, 3,000 men, the owners say their labour isn’t needed any longer.

Defeat

It’s a bitter defeat but ‘Tonypandy’ sparks a national debate. The iniquity of colliers struggling to dig out enough coal to keep their families fed – from seams that are fractured and full of stone – triggers widespread demands for an earnings safety net.

A year after the mid-Rhondda miners return to work, the Government brings in a Minimum Wage Act. It may be the most valuable legacy of the Tonypandy Riots – a principle as relevant and as debated today as was back in 1912.

Something else happens that year, something that shows that all of this has been about more than pounds, shillings and pence.

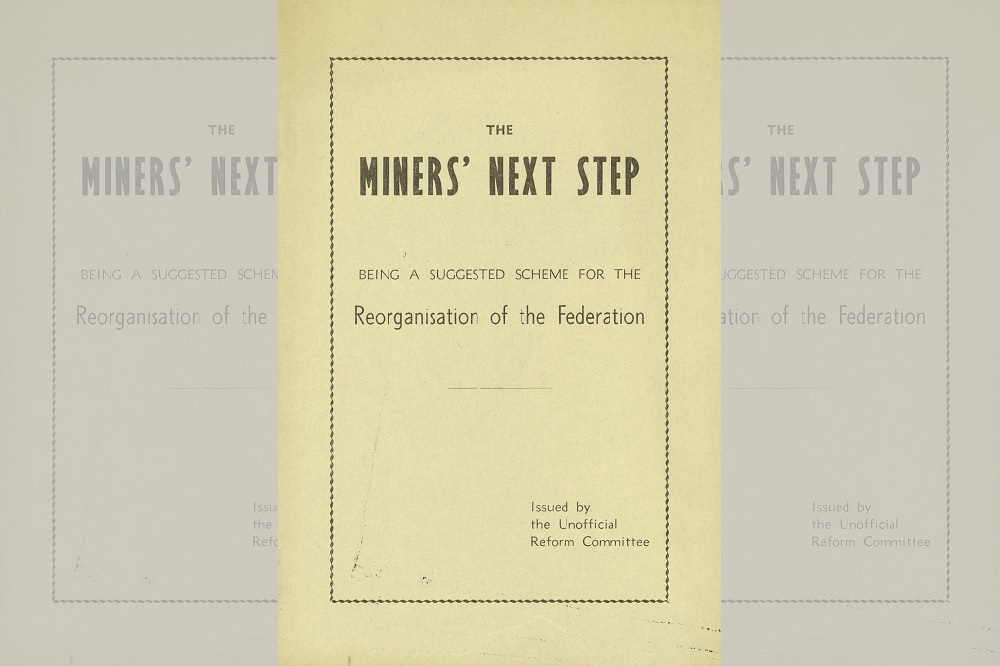

The Miners’ Next Step

In mid-Rhondda, the new generation of union leaders publish The Miners’ Next Step. It’s only the miners themselves, they argue, who have the real, ‘hands-on’ expertise in how to work a coalmine. Unless they’re in change of their own working lives, the industry’s problems will never be solved.

But the answer they put forward in this visionary manifesto isn’t nationalisation – state ownership. In any dispute, that would just bring colliers into conflict with the forces of the state. And Tonypandy knows from painful experience what that means.

The Miners’ Next Step wants mines controlled by the miners themselves – not by the coal-owners, not by the Government, not even by full-time union officials like Mabon.

All leaders become corrupt, it declares, however noble their intentions. “No man was ever good enough, or strong enough, to have such power at his disposal, as real leadership implies.”

It’s a breath-taking set of proposals. It could only have come from a working class who’d lived through the Cambrian Combine Dispute.

More than half a century later, when the nationalised coal industry was convulsed by the disputes of the 1970s and 80s, its warning about the forces of the State being used against the miners took on a prophetic aura.

And what of Churchill? His name was never revered in South Wales like it was elsewhere. In Rhondda cinemas, his appearances in newsreels were routinely booed. His defeat in the General Election after the Second World War was cheered loudly – it paved the way for the creation of the Welfare State and the National Health Service.

Forty years after the events of 1910, ‘Tonypandy’ still irks Churchill so much that he uses a speech in Cardiff to preach what he calls ‘the true story’. He stopped the movement of troops, he claims, and sent in the Metropolitan Police with the sole object of preventing loss of life.

Well, maybe… up to a point. He did stop the troops – for just one day. But then they did come, they did stay, and they were used. In fact, they were key to the outcome of the strike.

So, when Churchill says the troops were kept in the background, that all contact with the miners was by London Police armed with nothing but rolled-up mackintoshes, he’s doing more than being economical with the truth.

He’s lying to protect his own reputation.

Winners

So who did ‘win’ the Cambrian Combine Dispute? Churchill? The Metropolitan Police and the British Army? The Chief Constable of Glamorgan? D. A. Thomas?

He was soon to be ennobled as Lord Rhondda; but in the long run it wasn’t coal magnates like him who got to define what the Rhondda was, what the Rhondda is, at its best, when it lives up to its true values.

And it wasn’t the shopkeepers of Tonypandy – as noble as some of them were – who got to decide what kind of community they could do business in.

Rhondda’s social ambitions weren’t limited even by Mabon, with his beguiling notions of compromise, that ‘half a loaf was better than no loaf at all’.

No, it was the miners themselves and their families who used the lessons of 1910 to re-define the Rhondda. And what a glorious, far-sighted vision it was.

To them, the Rhondda was a community built on solidarity, on being solid with each other, on looking out for each other in tough times, on what my father used to call ‘stickability’ – sticking it out and sticking together.

In my book, that’s true nobility.

People before profit

Now you might say I’m being starry-eyed about all of this – about what the Rhondda was and is. Fair enough. We all know of times when Rhondda people haven’t lived up to those ideals.

But I bet we can think of occasions when we have – when we’ve stood up for each other, and with each other, in really important ways. The courage and sacrifice of NHS staff, carers, teachers, bus drivers, binmen and many others in the pandemic is just one example.

In every part of the Rhondda, you’ll find small stories that shout one big message – this is a place where people put people before profit, where what matters to ‘us’ matters more than what matters to ‘me’.

The pits are gone now, the events of 1910 passed out of living memory. Mid-Rhondda is a changed place. Where the Ely miners went to work, children take their lessons in Nantgwyn School.

The Scotch Colliery pithead, to quote Max Boyce, is a supermarket now, and time has done to the Power House, the mine-owners citadel, what the strikers couldn’t, or rather, never intended.

But in their vision that the riches of the world we live in should be shared fairly, and in their determination to face up to forces that seemed much more powerful than they were, the miners of mid-Rhondda proclaimed that the labour of working people should never again be taken for granted, and showed that they were capable of imagining a world that works in the interests of us all.

You can listen to much more Valleys history in the Rhondda Heritage Hour every Wednesday afternoon at 3pm on Rhondda Radio: https://www.rhonddaradio.com/

The latest edition of the Rhondda Heritage Hour – including John Geraint’s account of the Tonypandy Riots – is available to listen to on demand here: https://www.mixcloud.com/RhonddaRadio123/rhondda-heritage-hour-6112024/

‘Up The Rhondda!’, John Geraint’s collection of exuberant and evocative essays, is available here: https://www.ylolfa.com/products/9781800994874/up-the-rhondda!

And John’s coming-of-age novel set in the 1970s has recently been reissued as ‘A Rhondda Romance’: https://www.cambriabooks.co.uk/product/a-rhondda-romance/

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

‘And what of Churchill? His name was never revered in South Wales like it was elsewhere. In Rhondda cinemas, his appearances in newsreels were routinely booed. His defeat in the General Election after the Second World War was cheered loudly.’ When I was a university student in digs in west Wales way back in the mid-1960s, my elderly landlady, who had married a Cardi but had been born and brought up in Tonypandy, still retained bitter memories of the suppression of the riots in her home town decades before. Although I didn’t entirely grasp it at the time – I… Read more »